| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of Africa

Chapter 8: "WIND OF CHANGE", PART I

1914 to 1965

This chapter is divided into two parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

Part II

| The Algerian War | |

| The Mau Mau Rebellion | |

| "The African Year": Independence Below the Sahara | |

| The Congo Crisis | |

| South Africa and Rhodesia: Segregation Forever |

World War I

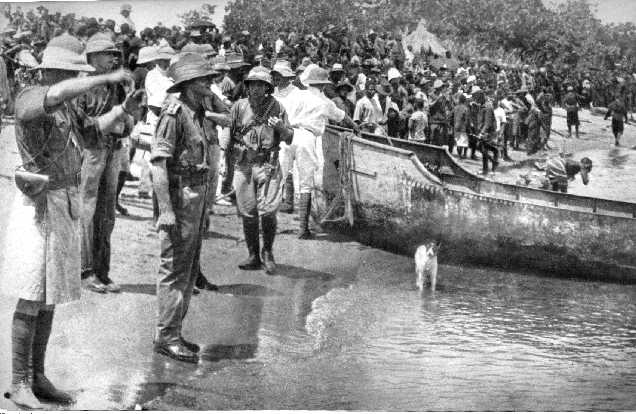

The most exotic campaigns of World War I were fought in Africa. If they have been all but forgotten today, it is because they were a sideshow to the European theater, where most of the bloodletting took place. However, they are fascinating stories in their own right, quite unlike any that happened in the trenches of France and Belgium.(1) For example, the wildlife added an extra dimension to the conflict. More than one battle was interrupted by a charging elephant, rhinoceros, or swarms of killer bees, which attacked Allied troops, Germans, and the African help of both with complete impartiality. Diseases and hideous parasites like the guinea worm were more dangerous than enemy soldiers; in one month (July 1916) the ratio of non-battle casualties to battle casualties reached as high as 31.4 to 1. The longest naval engagement of history was fought in a river delta of German East Africa, where it took 255 days and 27 British ships to locate and sink a single German cruiser, the Konigsberg.

Neither side was prepared to fight in Africa when the war broke out in August 1914, but the Allies had the advantage because Britain ruled the waves. The smallest German colony, Togoland, was defended by 568 policemen; it was overrun by French and British forces in only three weeks. The conquest of German Southwest Africa by the South Africans was a model campaign, but it was delayed until early 1915 when some diehard Boer War veterans made an unsuccessful bid for independence. In Cameroon, an Anglo-French force captured Douala, the capital, by the end of September 1914, but the Germans withdrew into the interior, where jungle conditions and 400 inches of annual rainfall made for some very slow going; here they resisted the Allies until February 1916.

The campaign on Lake Tanganyika was truly bizarre. This long lake had a shore that was shared by three colonial powers: Germany on the east, Belgium on the west, and Britain on the south. When the Germans on the lake began to attack Belgian shipping, the British decided it was their duty to get some boats in there and establish Allied dominance. However, the naval officer who led that expedition, Lieutenant Commander Geoffrey Spicer-Simson, must rank as the looniest military figure of all time; his arms and legs were covered with tattoos, and he acted like a character from "Monty Python's Flying Circus." Previously, Spicer-Simson's only claim to fame was that he was the oldest lieutenant commander in the Royal Navy; he had worked behind a desk for most of his career, and got the Tanganyika assignment because no other officer volunteered to take it. The two ships he was put in charge of were wooden, 40-foot-long launches that had been built by the Greek air force; since they had to be transported by rail from Cape Town, steel warships were not feasible. They bore numbers instead of names, so Spicer-Simson christened them Dog and Cat. When his admiral protested that these weren't appropriate names, Spicer-Simson renamed them Mimi and Toutou.

Things got even more odd after the British reached the lake. Spicer-Simson started wearing skirts (not a sarong or kilt, mind you, but a skirt), which he claimed his wife had made. Whenever a decision had to be made, he usually made the wrong one, but incredible luck saw him through anyway. As a result, his two launches captured a German launch, the Kingani, in their first battle (Spicer-Simson renamed it the Fifi). In the second battle they sank a larger steel ship, the Hedwig von Wissmann; of course Spicer-Simson got the credit for both victories. Then some British soldiers marched up from Rhodesia to capture the main German fort on the lake; this time Spicer-Simson kept his squadron in port, a move which gave the Germans enough time to escape in their boats. He may have felt that he didn't need to risk himself anymore, now that he was a hero in London. A local African tribe, the Ba-HoloHolo, thought that madness was next to godliness, so they made clay images of Spicer-Simson and paid homage to him when he took a bath.

The Ottoman Empire entered the war on Germany's side in the fall of 1914; twice it tried to take back Egypt from the British. Though these invasions failed to penetrate the British lines of defense in the Sinai, the sultan could still make trouble by proclaiming a jihad against the Allies.(2) Besides a few tribes in Arabia, the sultan of Darfur responded to this call. His state had remained autonomous after the British conquered Sudan in 1898, so when he was killed in battle in 1916, the British occupied Darfur and terminated the sultanate. The Sanussi also responded to the call; in November 1915 they launched a series of raids from their home base in Cyrenaica, and managed to capture several oases in Egypt's western desert before the British drove them back in 1917.

The French leaned heavily on their colonies for men and supplies to support the war effort in Europe. Blaise Diagne, the Senegalese member of the French National Assembly, persuaded many Africans, especially Senegalese, to join the French armed forces.(3) Other West Africans, however, fled to the nearest territories that were not under French rule (Gambia, Portuguese Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia, and the Gold Coast) to avoid conscription. Rebellions broke out in Mali and the Volta region in 1915, and northern Dahomey in 1916. The Tuareg were exploited most of all, through heavy taxation, confiscation of grazing lands and livestock, and interruption of the salt trade. Because their location in the middle of the Sahara left them with no place to run to, they revolted in 1916. Kaosen ag Muhammad, a Tuareg chief in northern Niger, besieged the French fort at Agades; the French captured and executed Kaosen in 1919, but instability in the area continued until the early 1930s.

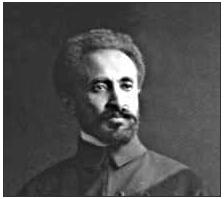

Abyssinia's king, like the sultan of Darfur, came to grief because he picked the wrong side. A year before the war began, seventeen-year-old Lij Iyasu succeeded his grandfather, Menelik II. He opened communications with Sayyid Muhammad, the Somali leader (see the next section), and apparently converted to Islam; that by itself disqualified him from being king, as far as the Ethiopian Orthodox Church was concerned. During the war he openly favored the German agents that came to his country, and dreamed of creating a Moslem empire in the Horn of Africa, one that would include Eritrea and the British and French parts of Somaliland. For the church and the rest of the royal family this was too much, so in 1916 they got together to depose Lij Iyasu and replace him with his aunt, Zauditu. A cousin of Zauditu, Ras Tafari Makonnen, was named heir apparent; he may have been the mastermind behind the coup. Ras Tafari would be crowned Emperor Haile Selassie I in 1930.(4)

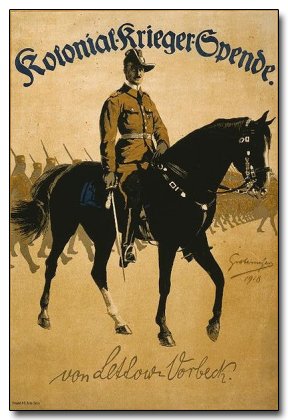

German East Africa was the toughest nut to crack; in fact, the campaign there outlasted the entire war. This colony was nearly self-sufficient, so economic blockades against it didn't hurt much. Furthermore, the German commanding officer here, Lt. Col. Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, was a military genius. He had 3,000 German soldiers and 11,000 African askaris (warriors), and unlike many white men of that day, he recognized that the African could fight just as well as the European if given the right equipment and training. It took a long time for the Allies, especially the South Africans, to accept this fact.(5)

Lieutenant Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck.

The first three British invasions of German East Africa were skillfully thrown back. Finally, the British got a commander who was not downright blimpish--Jan Christian Smuts, who we last saw as a guerrilla leader during the Boer War. In March 1916 he launched a new invasion in the Kilimanjaro area, and Belgium attacked from the northwest, annexing the heavily populated Ruanda-Urundi corner of the colony. But Lettow-Vorbeck was more clever than Smuts. His strategy was not to defeat the Allies, but to delay them. He knew all along that the fighting in Europe was more important than what happened here, and even if the whole colony was lost it would be regained at the conference table, if Germany won the war. Consequently his main goal was to draw Allied soldiers out of Europe and keep them from going back. Whenever the Allies made a move to capture Lettow-Vorbeck, he would withdraw instead of defending the territory. He also used the local climate to his advantage (for some reason the Germans were always less bothered by diseases than their opponents), and practiced a scorched-earth policy, which slowed down the Allies more. Whenever it looked like the Allies would stop pursuing, the Germans would turn around and give them a bloody nose, and the fox-and-hound chase would resume. During 1916 half of German East Africa was conquered; by late 1917 Smuts had confined Lettow-Vorbeck to the colony's southeast corner. Still, this was a hollow victory as long as the Germans remained at large. During the war, more than 120,000 Allied troops (Portuguese, British, Belgians, Indians, West Indians, Rhodesians, Nigerians and South Africans) would be committed to East Africa. 20,000 of those soldiers would be killed, along with 20,000 African noncombatants (workers, porters, etc.); again most of the casualties were caused by disease.

The last year of the war was the strangest of all. In November 1917 a zeppelin loaded with supplies was sent to East Africa from Germany; it got as far as Sudan before a mysterious radio message called it back. But Lettow-Vorbeck didn't need it anyway. At the same time his force escaped into Portuguese East Africa (Portugal had declared war on Germany in March 1916). The Portuguese defended their territory abysmally, and the natives welcomed the Germans as liberators. The Germans captured more food, ammunition, arms, etc. than they could possibly carry, and the looting of a Portuguese vineyard became an especially welcome event. The army was outnumbered, surrounded on all sides, forced to live off the land, and faced with no possibility of winning on its own, but morale was never better. When British troops arrived at the ports of Mozambique, the Germans turned around and re-invaded German East Africa. They found Allied resistance here too much for their dwindling force to handle, so Lettow-Vorbeck turned west and entered Northern Rhodesia (Zambia). At this point he received news that the war was over, so on November 25, 1918, two weeks after the war ended in Europe, the only German army that had never been defeated formally surrendered at the town of Abercorn. Lettow-Vorbeck had 155 Europeans, 1,156 askaris and 1,598 carriers left at this point. He received a hero's welcome when he returned to Berlin, for upholding military honor so far away from home, and because the Germans had little else to cheer about.

Once the war was over Germany's colonies were quickly disposed of. France got most of Togoland and Cameroon, except for a strip on the western border of each, which went to British-ruled Nigeria and the Gold Coast. Southwest Africa went to South Africa, while German East Africa was divided into British-ruled Tanganyika and Belgian-ruled Ruanda-Urundi. The acquisition of Tanganyika fulfilled Cecil Rhodes' dream from the previous generation, of a British-ruled African empire that would stretch all the way across the continent from north to south. All of these territories were supposed to be temporary "mandates," which would be given independence when the inhabitants were ready to stand on their own. Permission to occupy the mandates came from the League of Nations, the international organization set up after the war, but in practice the occupying powers ruled them much like their prewar colonies. South Africa, for example, treated Southwest Africa as if it had just gained a fifth province.

Troubles in the Italian Empire

Other postwar adjustments were made to reward Italy for supporting the Allies; the British and French altered their frontiers in North Africa to enlarge Italian-ruled Libya, and Britain gave the northeast corner of Kenya to Italian Somaliland, because the population in it was mostly Somali. However, the Italians found it much more difficult to take control over these areas. The Libyans and Somalis were usually cooperative when the authority over them was Moslem, like the Ottoman Empire, but they wanted nothing to do with the Christian Italians. Since 1891 Sayyid Muhammad Abdile Hassan, a religious leader who lived in British Somaliland, had been stirring up trouble, encouraging attacks against the Italians, the British, and the Abyssinians; his British opponents called him the "Mad Mullah." Today the Somalis regard him as the founder of Somali nationalism, because he was the first to make the Somalis see themselves as part of a nation, rather than simply members of a clan. However, he died without leaving a successor in 1920, allowing Great Britain and Italy to set up standard colonial governments in the Horn of Africa.

Libya proved to be even tougher, because as soon as the Italians had taken the Libyan coast in 1912, the Sanussi Brotherhood transformed itself from a network of religious schools to a full-blown nationalist movement. Egyptians, Arabs and Turks sent money and arms to the Sanussi, especially after Italy entered World War I. When the war ended the head of the Sanussi, Sayyid Ahmad, went into exile at Constantinople, and Sayyid Idris (1890-1983), his nephew and a grandson of the Sanussi founder, took over. Idris tried to reach some sort of agreement with the Italians that would recognize Italian rule in return for autonomy in Libya's interior, but then in 1922 Benito Mussolini and his Fascists seized power in Italy, and Mussolini denounced these agreements. Arab leaders in Tripoli and Benghazi responded by recognizing Idris as the emir of all Libya, and Idris withdrew to Egypt, expecting a military response from the Italians. It came soon enough, and for the next nine years about a thousand armed Bedouins fought 20,000 Italian soldiers. To subjugate Libya's interior, the Fascists resorted to aerial bombardment and the herding of civilians into concentration camps, since they were giving the Bedouins their support. Thus, the war was an early preview of the destruction and inhuman brutality that would characterize World War II. Not until the 1931 capture and public execution of Sidi Umar al-Mukhtar, the Sanussi military leader, did resistance end, allowing the Italians to claim that Libya had been completely pacified.

The Beginnings of African Nationalism

Reports of Italian atrocities in Libya disgusted the Western world. Other European powers had shown similar heavy-handed behavior during "the Scramble for Africa," but that was done by an earlier generation, and now most colonial overlords, especially the British, were trying to give the natives some say in how they should be governed. By contrast, Marshal Rodolfo Graziani, the Italian leader of the "pacification," was fond of dealing with captured Libyan nationalists by throwing them out of airplanes, decorating the desert with red blotches.

In the previous chapter, we looked at how Africa came under Western rule. After the conquest, Europeans looked supreme almost everywhere. Even in Abyssinia and Liberia, the two countries that survived the "scramble," independence was in a precarious state; Italy would invade Abyssinia before long, and Liberia's economy was deeply in debt to the Firestone rubber company. Slavery had been abolished wherever the West could enforce its authority, but only a racist could think that making the black man a second-class citizen was much of an improvement. For a period of roughly seventy-five years, from 1885 to 1960, maps of Africa were marked with the same colors used to identify nations in Europe, and the African was rarely heard from, even in his own land.

Once the "scramble" was over, some Europeans had misgivings about it. It appeared as if the colonial powers had simply jumped in to grab as much as they could, and then expected to rule their gains as smoothly as if they had no inhabitants. Merchants wondered if the effort to conquer was worth it, because there were few easy profits to be made, except in South Africa. As early as 1902 Winston Churchill, one of the key individuals who had made imperialism a success, wrote that "the inevitable gap between conquest and dominion becomes filled with the figures of the greedy trader, the inopportune missionary, the ambitious soldier, and the lying speculator, who disquiet the minds of the conquered and excite the sordid appetites of the conquerors. And as the eye of thought rests on these sinister features, it hardly seems possible for us to believe that any fair prospect is approached by so foul a path."

Another early critic of imperialism was Mary Kingsley, a Victorian-era traveler who questioned whether the new rulers really understood what they had destroyed, and poked fun at how astonished they were when the natives didn't act grateful to those who had saved them from savagery. She wrote that the imperial adventure was like "that improving fable of the kind-hearted she-elephant who, while out walking one day, inadvertently trod upon a partridge and killed it, and observing close at hand the bird's nest full of callow fledglings, dropped a tear, and saying 'I have the feelings of a mother myself,' sat down upon the brood. This is precisely what England representing the 19th century is doing in . . . West Africa. She destroys the guardian institution, drops a tear and sits upon the brood with motherly intentions; and pesky warm sitting she finds it."

Colonialism had created Western societies in the Americas and Australia, but there never were enough Europeans to do the same thing in Africa. When South Africa became independent in 1910, it had six million people, of which 22 percent (1.32 million) were white. The second largest European community on the continent was in Algeria; Algeria's population in 1914 was 5.25 million, of which three quarters of a million (14 percent) were Europeans. Elsewhere, white people were only a common sight in colonial capitals and ports like Zanzibar; the typical African lived unaffected by the hospitals, schools, railroads and industries that were built to serve as an infrastructure for the colonies. When the rulers tried to make their subjects pay taxes, many Africans chose to become peasants or migrant workers, because then they retained more control over their lives than they would have as wage-earning workers. As a result, to most outsiders Africa was as mysterious and misunderstood as it was before the scramble began, and would stay that way until independence came.

Of course, in a place as large as Africa, colonialism didn't affect everyone the same way. Those tribes which cooperated with the rulers were treated better than the other tribes. Among such privileged tribes were the Lozi of Northern Rhodesia, the Swahili on the east coast, the Baganda of Uganda, the Tutsi of Ruanda-Urundi and the Fulani of northern Nigeria. Likewise, the tribes which resisted suffered the most; several revolts broke out in the opening years of the twentieth century, but all of them were put down before World War I began. Losing tribes included the Ndebele and Shona, who saw their land taken by white settlers in Rhodesia, the non-Merina tribes of Madagascar, who fought against both the French and their former Merina rulers, and the Bunyoro of Uganda, who felt compelled to be anti-British because their Baganda enemies were pro-British. Worst of all was the fate of the Herero, a Bantu tribe in Southwest Africa; in the aftermath of their 1904 rebellion, the Germans exterminated two-thirds of the Herero, confiscated their land, and would not allow the survivors to keep cattle. Most of the Herero were thus forced to take jobs from their German masters, except for the few that managed to escape across the border into Bechuanaland.

In the early twentieth century, the most frequently seen Westerners were missionaries. The churches of Europe and the United States now supported missionary activity more than they ever had before. Here the goal was to win as many African souls to Christ as possible, and in most places below the Sahara, they were so successful that many Africans were soon becoming ministers, teachers and evangelists, because there weren't enough non-Africans to fill all available posts, except in supervisory positions. Islam also worked to gain new members, by establishing religious schools and brotherhoods in the areas that were Moslem already. Remembering past experience, most Christian missionaries chose to stay out of Moslem areas, so about the only place where Christianity and Islam competed for the same people was in southwest Nigeria (the Yoruba tribe).

The Christian missionaries also did very important humanitarian work. The most famous example is Dr. Albert Schweitzer (1875-1965), who built a hospital at Lambaréné in Gabon and was widely admired for the books he wrote on philosophy and theology; his tireless promotion of life and the brotherhood of man won him the 1952 Nobel Peace Prize. Others built schools, because they felt their converts had to learn to read and write before they could understand Holy Scriptures. In the process, the students got a Western-style education, and in a Western-run society, that put them in a position to challenge the old royal and priestly families. At first, they only wanted to apply what they had learned to the churches they joined, either by rising to positions of leadership in those churches, or by starting new churches of their own that would be entirely African.(6) It wasn't long, however, before they got the idea of doing the same thing in politics; the pre-1914 rebellions had failed to return Africa to return to its traditional way of life, but what about Western-style states run by Africans?

These early nationalists preferred using Western, Christian terms to express their views, rather than African ones. One good example was Charles Domingo, who wrote a pamphlet in 1911 that explained, in broken English, what was wrong with the behavior of Nyasaland's European rulers:

"There is too much failure among all Europeans in Nyasaland. The three combined bodies--Missionaries, Government and Companies or gainers of money--do form the same rule to look upon the native with mockery eyes. It sometimes startles us to see that the three combined bodies are from Europe, and along with them there is a title Christendom. And to compare and make a comparison between the Master of the title and his servants, it provokes any African away from believing in the master of the title. If we had power enough to communicate ourselves to Europe, we would advise them not to call themselves Christendom, but Europeandom. Therefore the life of the three combined bodies is altogether too cheaty, too thefty, too mockery. Instead of 'Give', they say 'Take away from'. There is too much breakage of God's pure law as seen in James's Epistle, chapter 5, verse four."

The important point to be made from the above quote is that Charles Domingo was judging the Europeans by their own moral standard, namely the New Testament. He felt that God's law as put forth in the Bible was suitable for Africans, so he did not see Christianity as a "white man's religion," nor did he call for anyone to abandon it; he simply felt that Africans would do a better job of practicing it, if they were in charge.

A few Africans managed to go to Europe or America to complete their education and become doctors and lawyers. When they returned, however, they did not get the jobs or status that they wanted, so these dissatisfied young men started forming political associations. Most of the meetings of these early organizations were held in Europe or the United States, because Africa didn't have a good meeting place or a significant audience for them. William E. B. Du Bois, a co-founder of the NAACP, hosted four of the earliest meetings, called Pan-African congresses, between 1919 and 1927; besides African nationalism, they promoted closer ties between Africans and blacks living elsewhere.

The first significant nationalist organization based in Africa was the National Congress of British West Africa, founded in 1918 by J. E. Casely Hayford, a lawyer from the Gold Coast, and expanded to include Nigeria in 1920. More important in the long run, though, were the activities of Nnamdi Azikiwe (1904-96), a Nigerian student. When he came home in 1935 after studying in America, he launched a popular press in both the Gold Coast and Nigeria, allowing him to spread his political ideas to the masses, something his predecessors had not done. Then he sent eight Nigerians and four Gold Coasters to study in America, all of whom would eventually become nationalist leaders. One of them, a teacher named Kwame Nkrumah, we'll be hearing a lot from later in this chapter.

Before World War II, this new intelligentsia did not get much attention; even most Africans ignored them. The Europeans also ignored them, because they were firmly in control, and since everything seemed to be going their way, they expected to stay in Africa for centuries, maybe even for a thousand years. When they felt the need to make a deal with the natives, they spoke to tribal chiefs and other traditional leaders. Little did they realize that by patronizing Africa's old nobility, they were cutting out the ground beneath them, and once the chiefs were discredited politically, the Western-educated Africans would rise to take their places.

The Rif War and Maghreb Nationalism

Marshal Lyautey was easily the best of the colonial governors. During World War I, Paris ordered him to send most of the French soldiers in Morocco back to France, and withdraw to the coast, if necessary, but he did such a good job that he didn't have to withdraw from any of the areas he had pacified. In fact, he and his counterparts in Algeria and Tunisia managed to contribute tens of thousands of Arab soldiers for the war on the Western Front.

Spain didn't do so well. In northern Morocco the Spaniards proved to be inefficient, unjust rulers, so in 1919 the Berbers of the Rif Mountains revolted, under two leaders, a charismatic chieftain named Abd el-Krim, and a brigand named Ahmed ibn-Muhammad Raisuli. Spain managed to defeat Raisuli, but in 1921 a Spanish general, Fernandez Silvestre, and 12,000 of his 20,000 troops were slain by Abd el-Krim in the battle of Anual. Abd el-Krim followed this up by driving the Spaniards into the towns on the coast, and proclaimed a "Republic of the Rif," though he really wanted to set himself up as sultan and found a new Moroccan dynasty. Because he had done so well against Spain, he grew overconfident and invaded the French portion of Morocco in 1925. This forced two European countries to form an alliance against him. General Miguel Primo de Rivera, the military dictator of Spain from 1923 to 1930, personally led an expeditionary force across the Mediterranean, while France's Marshal Petain brought in 160,000 French troops on the southern front. Within a year they forced Abd el-Krim to surrender; France exiled him to the island of Réunion until 1947, after which he was able to return and play another part in Morocco's bid for independence.(7)

The 1912 treaty that divided Morocco between France and Spain also declared Tangiers a "free city." However, they didn't put this into action right away, and Spain withdrew her agreement to this after World War I began. Then the Rif War persuaded Spain to restore the international zone in 1923. From 1940 to 1945 Spanish troops occupied Tangiers again, but after World War II it was declared a free city once more. Finally in 1956 it was incorporated into a now-independent Morocco.

An indirect casualty of the Rif War was Lyautey himself. In 1925 he submitted his resignation, because the French government was taking too long to send the reinforcements he requested during the war. It was an act of protest, and Lyautey didn't expect Paris to accept his resignation, because both he and the government knew that only lesser men would take his place; instead, the resignation was accepted. When he boarded the ship in Casablanca to leave Morocco for the last time, tears were reportedly streaming down his face.

Not long after Lyautey's departure, Muhammad V became the new sultan (1927). Because he was only seventeen years old, the French thought they could teach him to loyally toe the European line. Instead, he grew up to become a nationalist. When he met US President Franklin Roosevelt at Casablanca in 1943, he concluded that the Americans were the only real liberators among the Allies. One year later a Moroccan political organization appeared (Istiqlal, meaning the Party of Independence), and it had his full support, making him the automatic leader of Morocco's nationalist movement.

By the 1930s, France had controlled most of Morocco for a generation, Tunisia for fifty years, and parts of Algeria for a century. Because they had been there so long, the French worked hard to develop the Maghreb's infrastructure. A railroad ran all the way from Marrakesh to Tunis, and Casablanca had grown from a little fishing village in 1900 to a port that was home to a quarter of a million people. Europeans continued to settle here as well; this caused considerable stress for the Arabs and Berbers, who saw themselves crowded out of the best land and the best jobs. Because their birthrate was higher than the birth and immigration rates of the settlers, they grew poorer as time went on.

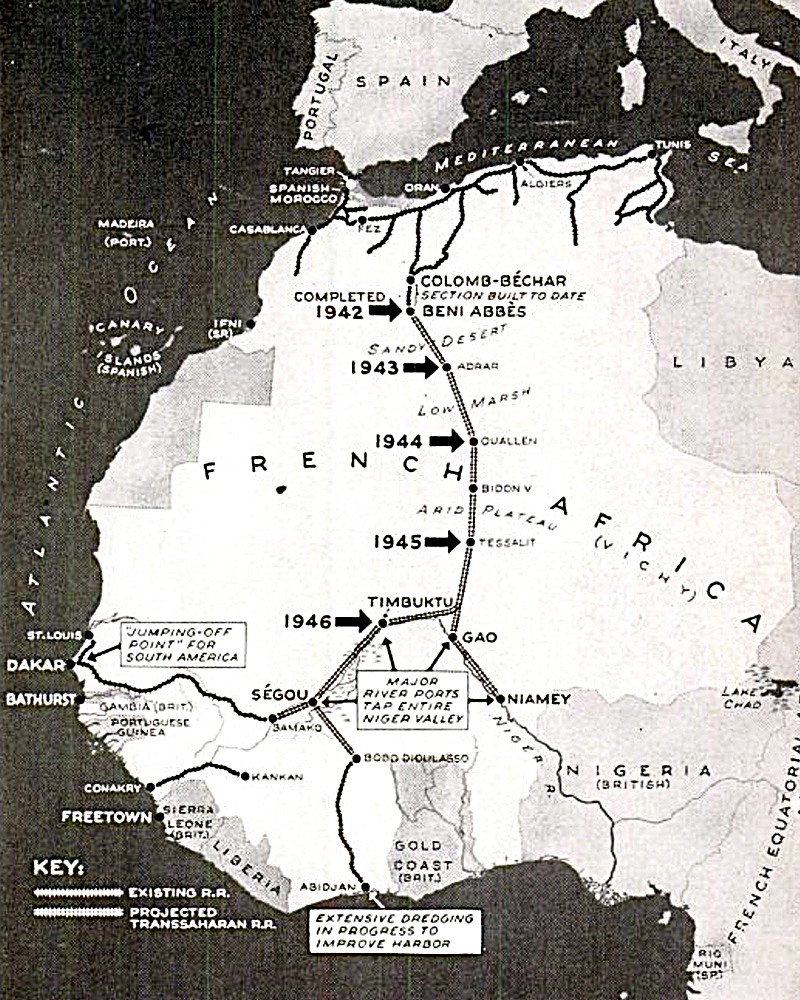

The French also had a proposal to build a trans-Saharan railway, across the Sahara between Algiers and Timbuktu. From Timbuktu, additional tracks would connect all of French West Africa, by going to Dakar in the west, Abidjan in the south, and Niamey in the east. Small, experimental pieces of the railroad were built in the 1930s and early 1940s, before the whole project was scrapped, due to extreme desert conditions, high costs, and World War II.

In Tunisia, nationalism was initially centered on the bey, the Ottoman-era governor who had been allowed to stay in office after the French took over. In 1920 the first Tunisian political party was organized; called the Destour (Constitution) Party, it called for the bey to get serious about human rights and ruling by law. However, it only appealed to a few wealthy citizens in Tunis, so it was disbanded five years later. In 1934 Habib Bourguiba (1903-2000) founded a more radical movement, appropriately called the Neo-Destour Party. Bourguiba called for making Tunisia a modern, secular society: "The Tunisia we mean to liberate will not be a Tunisia for Muslim, for Jew, or for Christian. It will be a Tunisia for all, without distinction of religion or race, who wish to have it as their country and to live in it under the protection of just laws." Because the Neo-Destour took aid from leftists and nationalists in France, Morocco, and Algeria, the government banned its newspapers, forced it to dissolve, and imprisoned Bourguiba from 1938 to 1942, when he was released by the Germans.

Algerian nationalists faced a real uphill struggle, due to the success the French had at trying to turn Algerians into Frenchmen. They had received a French education, and spoke French better than they spoke Arabic, but they stopped seeing themselves as French when even this could not get the settlers to treat them as equals. Still, like nationalists in other parts of Africa, they were a tiny minority among the native population. One of the first, Ferhat Abbas, wrote a lamentation about this in 1934: "Men who die for a patriotic ideal are honored and respected. But I would not die for an Algerian fatherland, because no such fatherland exists. I search the history books and I cannot find it. You cannot build on air." Not until the war for independence in the 1950s would most Algerians get the idea that they could become their own nation.

The Road to World War II Passed Through Ethiopia

Haile Selassie, like Menelik II, was dedicated to modernizing Abyssinia (known as Ethiopia from the mid-1930s onward), and he earned the respect of the outside world during the early years of his long reign. He gave Abyssinia its first constitution in 1931, and signed treaties with Great Britain, Italy and France that were considerably more evenhanded than the European-African treaties of the nineteenth century. Still, this could not protect him from a foreign dictator with evil designs on his country. Benito Mussolini resented how Italy had (with the possible exception of Spain) the least desirable empire in Africa, mere "crumbs from the sumptuous booty of others," and felt that Ethiopia would be a much richer colony to have. As early as 1928, Mussolini had plans to avenge the defeat Italy had suffered at Adowa, and since he couldn't use force while his troops were busy in Libya, he went to the League of Nations and announced that Italy had a natural right to Ethiopia, declaring that treaties signed in 1887, 1896, 1900 and 1908 recognized this right.

The League tried to prevent a war over this matter, but Mussolini was determined to fight anyway, and he got his excuse at the end of 1934, when Ethiopian and Italian troops clashed in the Ogaden Desert. The border between Ethiopia and Italian Somaliland was poorly defined, but the site of the incident, Walwal, was far enough inland that nobody considered it Italian territory; nevertheless, Mussolini claimed that his soldiers had been attacked. On October 3, 1935, without a declaration of war, Italian forces invaded Ethiopia in two columns, one from Eritrea and one from Mogadishu; ironically, they used roads that had recently been built as part of Haile Selassie's modernization campaign. This time the Italians were better prepared than they had been in 1896, and they made heavy use of warplanes and poison gas. By contrast, the Ethiopians were using the same equipment that they had at the beginning of the twentieth century, so they were hopelessly outclassed. Vittorio Mussolini, Il Duce's son, was a pilot in that war and described the thrill he got from bombing Galla tribesmen: "One group of horsemen gave me the impression of a budding rose unfolding as the bomb fell in their midst and blew them up."(8)

All the League of Nations could do was suggest a partition of Ethiopia (the Hoare-Laval plan); of course Haile Selassie rejected it. Economic sanctions were slapped on Italy, but these were nothing that could really hurt the Italian war effort, and an embargo on arms sales to both sides kept the Ethiopians from acquiring up-to-date weapons. Britain didn't even close the Suez Canal to Italian shipping, thereby allowing unrestricted transport of Italian soldiers and supplies to the war zone. On May 5, 1936, Italian tanks entered Addis Ababa, and Haile Selassie fled the country. He went to the League of Nations, where he made an eloquent appeal to the conscience of the world: "I pray to Almighty God that He may spare nations the terrible sufferings which have just been inflicted on my people." His plea went unanswered, and the dictators who arose in the 1920s and 1930s were encouraged to act more boldly, convinced that no one would punish them for their deeds. Before 1936 was over, Germany's Adolf Hitler would break the Versailles treaty by moving soldiers into the Rhineland, and Hitler and Mussolini would form the alliance known as the "Rome-Berlin Axis." Instead of buying peace, the world would soon have to go through the most destructive war of modern times, because it waited too long to stop the aggressive activities of the dictators.(9)

Haile Selassie I.

More activity would occur in Africa after World War II began. France surrendered to the Axis in June 1940, and the British were concerned that the French fleet, intact up to this point, would soon be used against them; Britain was fighting alone at this time, so having the French ships on the side of Germany and Italy would be enough to turn the balance of sea power against them. As a result, in July the British reluctantly attacked and seriously damaged the French ships stationed near Oran, Algeria (three battleships, two destroyers and one carrier). The next day (July 4, 1940), two Italian brigades crossed the Eritrean-Sudanese border to capture the towns of Kassala and Gallabat, and the French responded to the loss of their ships by attacking Gibraltar from Morocco.

In August Mussolini used his forces stationed in Ethiopia to invade British Somaliland. Britain was not a helpless opponent like Ethiopia, and Italian casualties were heavy, but with Britain itself now under attack by the Luftwaffe (the German air force), there was nothing to spare for the colonies of Sub-Saharan Africa; sixteen days after the invasion started, the last British survivors were evacuated from Berbera. With French Somaliland now under the control of Vichy France, the pro-German puppet government set up after the French collapse, the entire Horn of Africa now belonged to the Axis.

However, it was Italy's last triumph, and it only lasted for five months. By the end of 1940, Great Britain was preparing for a counterattack, now that the Battle of Britain was over. On January 19, 1941, the British launched a double offensive, one army group attacking Eritrea from Sudan, and the other attacking Italian Somaliland from Kenya. Haile Selassie personally led a guerrilla unit that went directly into Ethiopia from Sudan, and his son led another one. The Italians made a stand in a heavily defended gorge near the fortress of Keren, which delayed the Eritrean advance until the end of March; once it fell Asmara and Massawa were taken easily. By this time Mogadishu had also fallen (February 25), another British force from Aden had landed at Berbera (March 16), and one more British force had entered southern Ethiopia from Kenya. The force in Mogadishu struck across the Ogaden to reach Jijiga, and then all Allied units converged on Addis Ababa, which was liberated on April 6.

The remaining Italians were confined to two areas, Tigre province and the region southwest of Addis Ababa. The Duke of Aosta, the Italian commander, was captured on May 19 after a two-week battle in another pass, Amba Alagi. Those in the southwest surrendered by the end of June, and with the capture of Gondar on November 27, Italy's empire in East Africa was no more.(10)

Haile Selassie returned in triumph to Addis Ababa on May 5, 1941, five years to the day after he had been forced to leave. At this point the old imperialist reflex kicked in, and the British tried to put Ethiopia under a military administration, the way they had just done with Eritrea and Italian Somaliland. Instead, Haile Selassie had his way, and was allowed to resume his reign.

The Liberation of French Africa

France's overseas colonies, and most of the French citizens living in them, submitted to the Vichy government without a struggle. By the summer of 1940, Charles de Gaulle was the only French leader who still wanted to continue the war on Britain's side. At first he had to use London as his home base, but in August 1940 he and his Free French were able to capture Libreville in Gabon. September saw a combined British-Free French attempt to take Dakar, the capital of French West Africa, but it failed. Then in October de Gaulle went after Douala in Cameroon, and Brazzaville, the capital of French Equatorial Africa; he succeeded in both places, with the help of Felix Eboué, the governor of Ubanghi-Chari (today's Central African Republic), and declared Brazzaville to be the Free French capital.(11)

In the Gulf of Guinea, the Spanish-ruled island of Fernando Póo became the site for a secret mission. German submarines were refuelling somewhere in the rivers of the Vichy French-ruled colonies; the British Admiralty wanted to know where the sub base was, and what else the Axis was doing in West and Equatorial Africa. They figured the best way to get the intelligence they wanted was to steal the Axis ships currently anchored at Fernando Póo: an Italian merchant ship, the Duchessa d'Aosta, the German tugboat Likomba, and a yacht owned by a Spanish fascist, the Bibundi. To do this they sent a commando unit from the Special Operations Executive (SOE), an organization set up in 1940 to conduct espionage, sabotage and reconnaissance missions behind enemy lines. Few people at the time knew the SOE existed, and those who did gave it nicknames like "the Baker Street Irregulars," "Churchill's Secret Army," and the "Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare." What made this mission tricky was that Spain was a neutral nation, and it might join the Axis if the agents committing the heist blew their cover.

The mission was called Operation Postmaster, and it began with the agents sailing from Lagos, Nigeria to Fernando Póo on two tugboats. On January 14, 1942, they sneaked into the Spanish harbor, making sure they arrived on a moonless night and that they came after the harbor lights were turned off. Other agents distracted the harbor guards and the officers of the ships by inviting them to a big party at the local casino, where lots of liquor was served. While the party went on, the commandoes boarded the ships, and surprised the crews so completely that they jumped ship, or surrendered without a fight. Then they set off explosives to break the chains holding the ships to the docks, and the British tugboats took off, heading back to Lagos with their prizes in tow. Of course the folks at the party heard the explosions, and at this late hour, they were either too drunk or too shocked to keep the commandoes from escaping. The Spanish government was furious when Madrid got the news, and called it "an act of piracy," but there wasn't enough evidence to prove that the British government had planned the caper -- which is exactly how London wanted it.

For more on Operation Postmaster, here is a page about one of the agents involved. I wrote about it here because this and other stories about the SOE inspired Ian Fleming, a British naval intelligence officer. After the war, when Fleming wrote his James Bond novels, he modeled the James Bond character after members of the SOE. A lot of today's pop culture came from that, not to mention careers for actors like Sean Connery, Roger Moore, Timothy Dalton and Daniel Craig.

Before the war, a few anti-Semites had proposed exiling all or part of Europe's Jews to Madagascar. However, the island's backwardness meant this never looked like a good idea; a study by the Polish government in the 1930s suggested that Madagascar could only accommodate 5,000 to 7,000 Jews, and one opinion put the number as low as 500. Nevertheless, Adolf Hitler heard about it in 1938, and he thought the "Madagascar Plan" deserved serious consideration, especially after Germany conquered France. At one point, the plan called for Vichy France to hand over Madagascar to Germany, and the island's French citizens would be removed to make room for more Jewish exiles. But because World War II was not a short war, the plan was never tried. Deportations to a place like Madagascar were not feasible as long as the British navy could fight back, and Hitler's 1941 invasion of Russia vastly increased the number of Jews under German rule. Rather than try to relocate all of these unfortunates, the Nazis now went ahead with a more "final solution."

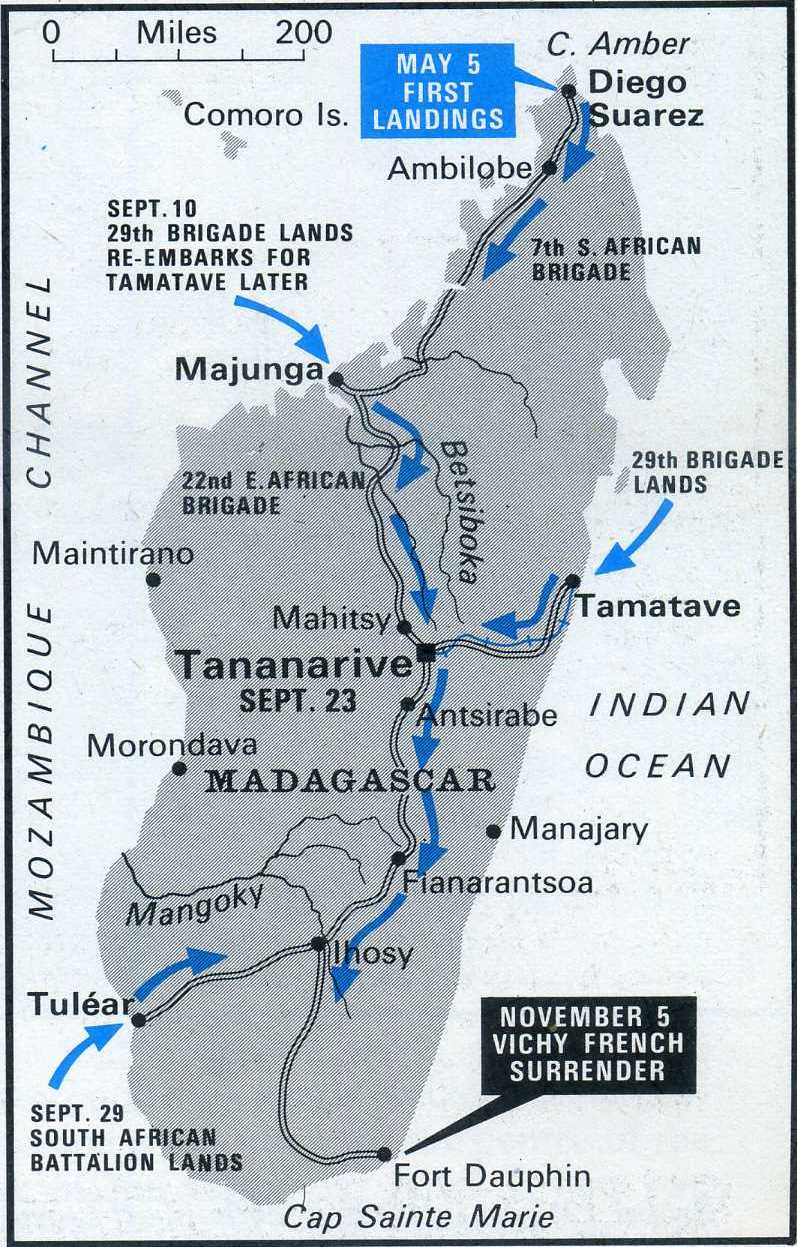

In the Indian Ocean, a Japanese raid on Sri Lanka (April 1942) threw a scare into the British. Britain feared that the Japanese would capture that island and move on to Madagascar, where they could cut off Allied shipping around the Cape of Good Hope. To prevent this, the British landed at Diego Suarez on May 5, occupying Madagascar's northern tip. Then on May 30, a Japanese mini-sub showed up there, sank a tanker and damaged the battleship Ramilles. More ships were torpedoed in June and July, 25 in all before the Japanese vessels withdrew; the Allies tried unsuccessfully to avoid attacks by sailing around Madagascar's east side, rather than through the Mozambique Channel. Realizing that the Japanese could still have a base on Madagascar as long as the Vichy French held any part of the island, the British decided they would have to conquer it all. However, the Vichy French were just as tough to beat here as they were at Dakar, so in September additional landings were made at Tamatave, Majunga, and Tulear. Antananarivo fell to them on September 23, and the Vichy French withdrew to the far south, where they finally surrendered on November 5, 1942. Appropriately, they gave up at Fort Dauphin, the same place where the French had set up their first outpost on Madagascar, almost exactly three hundred years earlier (see Chapter 6).

The Madagascar campaign.

Also in November 1942, a second attempt on Dakar was made, using Americans. The United States had been in the war for nearly a year, but this was the first activity outside of the Pacific involving American troops. This time the Allies succeeded, and French West Africa was free. Then Operation Torch, the campaign to liberate French North Africa (see below), got underway, and de Gaulle finally had a base close enough to the European theater to be useful.

The See-Saw Struggle in North Africa

Shortly after conquering British Somaliland, Mussolini went after Egypt. Here the Axis had two objectives, the Suez Canal and the rich, recently discovered oilfields of the Middle East. Five Italian divisions, led by Marshal Graziani, left Libya in September 1940, advanced sixty miles and took the town of Sidi Barrani. Then they had to halt, because they had run out of gas. This was one of the characteristics of World War II's North African campaign: not only was the desert a tough place to live and fight in, but both sides found it difficult to keep their forces supplied, because the Allied ships sailing to Alexandria and the Axis ships sailing to Tripoli faced the constant danger of attacks from the enemy. In December the British commander in Egypt, Sir Archibald Wavell, began the counteroffensive, and Mussolini began receiving the same sort of bad news from Egypt that he was receiving from Greece, and would soon receive from Ethiopia. One British column followed the coast, taking ports like Bardia, Tobruk, Derna and Benghazi, while another struck directly across the desert to the Gulf of Sidra. The latter took El Agheila on February 9, and halted because it too had reached the limits of its supply lines. Still, it was the greatest Allied triumph to date: Cyrenaica had been conquered, nine Italian divisions had been destroyed, and 130,000 prisoners had been captured. On the Allied side, there were only 500 killed and 1,500 wounded.

General Erwin Rommel.

Only Germany could save Mussolini's empire, which was now crumbling on three fronts. Ethiopia was too far away for Hitler to come to the rescue, but he did dispatch enough planes, tanks and soldiers to turn the situation around in North Africa and the Balkans.(12) For North Africa he sent two armored divisions, soon to be known as the Afrika Korps, and his best general, Erwin Rommel, the "Desert Fox." It took until mid-April for the second division to arrive, but Rommel began his attack on March 24. The offensive was a complete success; the overstretched British forces crumbled and within three weeks Rommel had recovered all of Cyrenaica except for Tobruk. The Afrika Korps advanced as far as Buqbuq, about halfway between the Libyan-Egyptian border and Sidi Barrani. Rommel stopped there because he was busy with Tobruk, feeling that he could not move safely while a port behind him was in Allied hands, but the Australian division in Tobruk stubbornly resisted all attempts to dislodge it.(13)

Men of the 2nd Battalion, Leicestershire Regiment, defending Tobruk. Photo taken on November 10, 1941.

Two attempts to drive Rommel back across the border in May and June failed, prompting Prime Minister Winston Churchill to transfer General Wavell to a command in India. His replacement was Sir Claude Auchinleck, and he had a newly created force, the famous British Eighth Army. He also had a plan to recover the initiative, Operation Crusader, which got underway on November 18, 1941. Four weeks of heavy fighting followed in the vicinity of Tobruk, followed by a sudden retreat of the Germans and Italians to El Agheila. However, this was not the rout it appeared to be; Rommel was making a strategic withdrawal because he realized he could be isolated between Tobruk and Benghazi, if the British tried the same overland maneuver they had used in their last offensive. From Tripolitania, the Afrika Korps could recover quickly, while the Eighth Army was now 500 miles from its nearest base in Egypt.

In fact, Rommel was ready to try again just a month after pulling back. In a span of two weeks, from January 21 to February 6, he advanced rapidly, not stopping until he reached the Eighth Army's first defensive line, which ran from Gazala to Bir Hakeim, just west of Tobruk. Both sides paused here to gather strength for nearly four months, and then after a three-week battle, the Axis forces broke through.(14) This time Tobruk, the port that had held out against everything in 1941, was taken in a single day. Auchinleck fell back to the next line of defense, at Marsa Matruh in Egypt, but Rommel had an even easier time getting through this one. By the end of June 1942 he had reached El Alamein. Located sixty miles west of Alexandria, the British chose to stand at El Alamein because it was near the Qattara Depression, a rocky valley that is impassible to mechanized infantry and tanks; here it was easy to form a narrow defensive line between the Qattara Depression and the sea. If the Axis got past El Alamein, nothing would keep them out of the Nile Valley itself.

Auchinleck beat off the first attack on El Alamein in July, but instead of striking back, he planned on regrouping his forces until mid-September; he was good at defending a fixed position but overly cautious about going on the offensive. Most expected that Egypt would soon fall to the Axis, and in fact, many Egyptians, including King Farouk, looked forward to this happening, resenting the control Britain had over their country. In August, Winston Churchill flew to Cairo to see why Auchinleck wasn't moving against Rommel, and ended up dismissing him; in his place he put Sir Harold Alexander in charge of the North African theater, and a little-known general, Bernard Law Montgomery, in command of the Eighth Army. He hated getting rid of Auchinleck, but it turned out to be one of his best decisions; it restored the Eighth Army's morale, and in the new leaders Rommel finally met his match.

The Eighth Army withstood a second attack on El Alamein at the end of August, and Montgomery built up his forces until he had nearly twice as many men and tanks as Rommel did. On the night of October 23, 1942, he began a battle of his own with an artillery barrage from a thousand guns, which blasted holes in the minefields that the Germans had dug along the front line. Then he fooled the enemy with a fake build-up in the south that led them to think the main breakthrough would come there, so when it happened in the north, the surprise was total. Rommel, who was on sick leave in Germany, hurriedly came back to the front, and after nine days of nonstop bombings and assaults with new tanks and infantry, he decided he would have to pull back. Hitler foolishly gave orders to stand and fight to the last man, which delayed Rommel one more day until he realized these orders could not be followed. As a result, he barely managed to get the Afrika Korps out of Egypt, helped by sudden heavy rains that bogged down British vehicles in mud; the Italian units had to be abandoned altogether. By the time he was moving, he also realized that he could not rest again in Tripolitania, for by then the Allies had landed in his rear, in Morocco and Algeria. The result was one of the longest retreats in history, which didn't stop until he reached a new defensive perimeter in southern Tunisia, the Mareth Line. The Eighth Army pursued, taking El Agheila on December 16, and Tripoli on January 23.

The campaign to take back the Maghreb, Operation Torch, began with three amphibious assaults; 35,000 Americans landed at Casablanca, 39,000 Americans landed at Oran, and 33,000 Britons landed at Algiers (all on November 8, 1942). Vichy French resistance ended the next day when Admiral Darlan ordered a cease-fire; within a week all of Morocco and Algeria north of the Atlas mts. was in Allied hands. However, the Germans rushed reinforcements as soon as Hitler heard the news of the landings, allowing them to hold onto Tunisia as 1943 began.

For General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the new supreme commander of the Allied forces in Europe and North Africa, the biggest challenge of Operation Torch was keeping the troops united. Even at this late date, more than a century after the Napoleonic Wars, the British and French didn't get along very well, so their soldiers couldn't be put together. The Americans could get along with both--that's why 69 percent of the soldiers used in the landings were American--but they were mostly green recruits. Rommel tried to take advantage of these differences by staging his counterattack in the sector where Americans were stationed. In the battle of Kasserine Pass (February 14-25, 1943), he broke through and managed to recover much of southwest Tunisia. Next he planned to rush to the sea near Bône, Algeria, thereby cutting off the rest of the Allied troops from their supply lines and pinning them against the north wing of the Afrika Korps. However, this would be Rommel's last victory; by now Montgomery had reached the Mareth Line in the southeast and was beginning to penetrate it. Montgomery, Alexander and Eisenhower managed to coordinate their movements just in time to keep Rommel in the Tunisian bottle; the Allied forces were badly shaken, but not cut to pieces.

Today it is not clear who administered Tunisia during the final six months of the North Africa campaign. When Operation Torch began, Germany responded by eliminating Vichy France. In the case of Tunisia, either the Germans simply took it, or it was hurriedly placed under a joint Axis military occupation. Previously, Mussolini had said he wanted Tunisia for Italy, since it is just a few miles south of Sicily (remember how close the Carthaginian Empire was to the ancient Roman state). Some Internet historians have claimed that the Italians got Tunisia for this brief period, but the sources asserting this are not reliable.

In early March Rommel relinquished command and returned to Germany, a sick man again. After that it was simply a matter of squeezing the Axis-held area down to nothing. By mid-April only the northeast corner of Tunisia was left. The two main cities there, Tunis and Bizerte, were both taken on May 7, and the last defending soldiers laid down their arms on May 13, in the Cape Bon peninsula. For the Allies it was a great victory; not only had the Axis been completely cleared out of Africa, but they had also gained the experience they would need for the upcoming campaigns in Italy and France.

Decolonization Begins

During World War II, many Africans joined the British, French and Italian armies. For them, the war was an eye-opening experience. It was a dangerous job, of course, but they received better food and pay than they got at home, and away from Africa they were treated better. In addition, they got to see what the rest of the world was like, and because they were ordered to kill enemy white soldiers, they learned very quickly the white man was no demigod, but just as mortal and vulnerable to bullets as anyone else. And no matter which side they were on, they saw their white masters humiliated by defeat, at one time or another. Even South African blacks enlisted, though because South African law would not allow them to have weapons, they had to take noncombatant roles. A leader of the African National Congress put it this way: "The country is in danger. Even if a man has [sic] quarrelled with his wife, when he sees an enemy approaching his home, he gets up to settle with the enemy." When the soldiers came home, they resented the lower living standard, and lack of economic and political opportunity, compared to what they had experienced abroad, so they joined educated Africans in calling first for more rights, and later for complete independence.

At the end of World War II, five colonial powers remained in Africa (Great Britain, France, Portugal, Belgium, and Spain), and of those five only Britain and France were important on the world scene. They had divided Italy's colonial empire between themselves, so at this point their position looked stronger than ever. The truth of the matter was quite different, though. Two World Wars had exhausted them, and the two strongest nations of the postwar world, the United States and the Soviet Union, now put pressure on the nations of Europe to dismantle their colonial empires. The Soviet Communist Party had opposed colonialism on principle since they had seized power in Russia, and the United States set an example by letting go of its most important colony, the Philippines, in 1946. Because of this pressure, by 1948 the British and French had terminated their "mandates" in the Middle East, independence had come to the Indian subcontinent and Burma, and most of the rest of Southeast Asia was in revolt. Africa was far behind Asia when it came to political progress, but when Africans read the Versailles Treaty and the UN Charter, both of which called for self-determination for all peoples, they wondered why these couldn't apply to them, too.

One of the first calls for African self-determination was at a conference featuring several black politicians, the Fifth Pan-African Congress. Held in Manchester, England, in October 1945, they claimed to speak for all of Black Africa. William Du Bois led this conference, like the prewar Pan-African congresses, though he was now seventy-seven years old; the main speaker was Kwame Nkrumah of the Gold Coast. Also in attendance was Nigeria's Nnamdi Azikiwe, who set a deadline for independence: the British must get out in fifteen years, and eventually the other colonial powers must quit Africa as well. The only participant familiar to outsiders was Du Bois, and the British government paid no attention, but in the end what happened was remarkably close to what they had demanded.(15)

North Africa Rejoins the Arab World

Because Libya had been under Axis rule, it was the first African territory that the West set free after the war. After driving out the Italians and their German partners in 1943, the Allies put it under a joint military administration--Britain managed Cyrenaica and Tripolitania, and the Free French managed the Fezzan. The last time the Libyans had been heard from, it was clear that they wanted an independent state with the Sanussi Brotherhood in charge of it. And now that the United States and the newly created United Nations were watching, the ruling powers took the job of preparing the natives for independence seriously. Accordingly, Libya became independent in 1951, with the Sanussi leader now known as King Idris I. While Idris was king, Libya had two capitals: Tripoli for the government, and Benghazi for the royal residence.

King Idris I. From Wikimedia Commons.

Before leaving the Horn of Africa, the Europeans tried to alter the borders to better reflect the ethnic makeup of that region. Three different plans were proposed for Eritrea; in the end it was handed over to Ethiopia, so that Haile Selassie could have a seaport (1952). However, that turned out to be a hasty decision; the mostly Moslem Eritreans didn't want to be part of a Christian kingdom, especially after the Ethiopian government declared Amharic the only official language and insisted that all government jobs be filled by members of the Amhara ethnic group, thereby offending even the Christians from Tigre. Consequently the Eritreans revolted in 1961, beginning a long guerilla war that would last for more than thirty years.

Italian Somaliland was declared a UN trust territory after World War II. Because the British had enough to keep them busy elsewhere, the Italians were invited to come back in 1950, on condition that they hold the territory for no more than ten years and do nothing but prepare it for independence. Italy complied with these terms, and did a fine job during its second administration.

The Ogaden Desert, ruled by Ethiopia before the war, had been transferred to Italian Somaliland in 1936, after Mussolini's invasion. The British returned it in 1948, after trying to persuade the Ethiopians to give it up for a future Somali state, since the Ogaden's population is Somali. The Ethiopians refused, though the desert has no resources to make it worth keeping, creating another situation that would lead to war in the next generation.

Egypt was a place where nationalism had been going strong for decades; in fact, Egypt's nationalist movement got started before the British takeover, as we saw in the previous chapter. In 1914 the threat of a possible revolt or a Turkish invasion caused Britain to impose martial law on the Nile valley. The war saw terrible inflation and hardship for the Fellahin, who were used as cheap labor and saw their livestock confiscated by the army. Violent unrest broke out after the war ended, and the formation of a political party called the Wafd, led by Saad Zaghloul, prompted the British to terminate the protectorate in 1922, when everything else failed to put a lid on the unrest. The title of khedive was dropped, having gone out of date when the Turks lost control of Egypt, and the last holder of the title became King Fuad I. Technically this meant that Egypt was now independent, but Britain kept soldiers around to protect the Suez Canal and to intervene in the event of an emergency. In 1936 these troops were withdrawn to the canal zone. The same year also saw Fuad succeeded by his fat and foolish son Farouk, who was fated to become both a national embarrassment and the last king of Egypt. You can read the rest of the story about Egyptian nationalism in Chapter 15 of my Middle Eastern history.

There really wasn't a good reason for the British to keep the Suez Canal after India was gone, but because they had worked so hard to acquire and defend it, they couldn't bring themselves to let it go; instead, they built up their troop presence in the canal zone until they had seven times as many soldiers as the 10,000 allowed by the 1936 treaty. Another thorny issue was the Sudan. After the battle of Omdurman it was declared a jointly ruled territory, but everyone knew which member of the Anglo-Egyptian partnership pulled the strings. The Egyptians felt they should be the only rulers there, since the Sudan had been under the rule of Cairo for much of the nineteenth century. Because the British insisted on holding both the Canal and the Sudan indefinitely, while the Egyptians wanted them out completely, Anglo-Egyptian relations worsened as time went on.

In 1952 King Farouk was ousted by a military coup. For the next two years the president of Egypt was Major General Mohammed Naguib, but the real leader of the coup was Colonel Gamal Abdel Nasser, so in 1954 he dispensed with the front man, ruling alone for the rest of his life. For the first time in 2,300 years (since the XXX dynasty, see Chapter 4), Egypt had an Egyptian ruler who didn't have to obey the wishes of any foreign empire. He managed to reach an agreement with the British that settled the Sudan question, in February 1953. Since neither side would give up the Sudan if it meant handing it over to the other party, they went for parliamentary elections, followed by a three-year period of autonomy, and finally independence on January 1, 1956. When the elections were held, Egyptians hoped the Sudanese would vote to rejoin Egypt, while the British wanted elections to produce a pro-Western, anti-Nasser government. Independence came on schedule, but the election was a disappointment for both sides; though the pro-Egyptian parties got elected, once they were in office they changed their minds and chose not to become part of Egypt.

Like past leaders, Nasser paid more attention to Egypt's Asian neighbors than to Egypt's African neighbors. Therefore, most of his activities have already been covered in Chapter 16 of my Middle Eastern history. However, he did see himself as both an African leader and an Arab leader, and had a vision to make Egypt the foremost nation of both regions. One event during his career, the Suez Crisis, needs to be retold here because it marked the end of British involvement in Egypt.

Though he ruled as a dictator in all but name, Nasser was the benevolent kind of strongman, who put the needs of his people first. Along that line, he had a very ambitious development program, which began with the building of the world's largest dam across the upper Nile River, the Aswan High Dam. This dam would turn Lower Nubia into an artificial lake(16), but it would also prevent floods downstream, generate electric power, and provide water for future irrigation projects. At first he counted on aid from Western countries, especially the United States, to pay for the dam, but the Americans backed out in 1956 because of two things he did outside of Africa: he refused to get involved in the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union, and he assumed leadership of the Arab side in the Arab-Israeli Conflict, promising to drive the Jews into the sea. When he realized that Western aid was not coming, Nasser decided to use the Suez Canal to finance the dam, so he announced the nationalization of the canal, thirteen years before the Suez Canal Company's charter was due to expire. This move was legal so long as Nasser paid off the canal's stockholders, but the British would have none of it; they called for the assistance of France and Israel, and in October 1956 all three countries invaded the Sinai peninsula from the east, hoping to seize the canal and topple Nasser's regime. They got as far as the canal, and then international opinion forced them to stop, because this looked too much like the 1882 intervention that had brought Britain to Egypt in the first place. Both the United States and the Soviet Union agreed that gunboat diplomacy was no longer acceptable behavior, and they put pressure on the three attacking countries until they withdrew from Egyptian territory in the following year. Instead of being removed from office, Nasser emerged from the Suez Crisis as a hero, though in the end he had to accept Soviet aid, rather than wait for revenues from the canal, to get the Aswan High Dam finished.

Nasser's reputation was so high in the Arab world after 1956 that the government of Syria tried to escape its problems by asking for political union with Egypt. The new state, called the United Arab Republic (U.A.R.), flanked Israel on two sides; indeed, as it turned out, the Arabs couldn't agree on anything except that Israel was their common enemy. Once they discussed something else, internal tensions started to build. In 1961, three years after the union was declared, Syria changed its mind and pulled out. Nasser tried a looser federation between Egypt and Yemen, and attempts were made to bring Lebanon, Jordan and Iraq into the Egyptian-Syrian union while it lasted, but these efforts were even less successful. Nevertheless, the U.A.R. remained Egypt's official name until 1973, when Nasser's successor, Anwar Sadat, changed the country's name to the Arab Republic of Egypt.

In the Maghreb, the natives didn't think very highly of the French, after they had seen their land become a battleground between Vichy and Free French factions. Consequently the political evolution of this region accelerated after the war. Earlier in this chapter we saw a quote from Ferhat Abbas about the lack of Algerian nationalism in the 1930s; in 1946 he sang a different tune: "The Algerian personality, the Algerian fatherhood, which I did not find in 1936 among the Muslims, I find there today. The change that has taken place is visible to the naked eye, and cannot be ignored." In response, the European colonists called on the government of postwar France, the Fourth Republic, to promise it would always keep the Maghreb in French hands. Paris tried to placate North African natives by offering full citizenship to more of them, and dropping the requirement to renounce any aspect of Islam. However, the Moslems who could take advantage of this privilege were still in the minority; the colonists didn't want any concessions granted to the natives whatsoever, while French politicians got nervous about the idea of treating Frenchmen, Arabs and Berbers as equals, because it could mean more than a hundred Moslem deputies getting elected to the French Parliament. Thus, the government's concessions were always too little to satisfy the nationalists.

In accordance with the wishes of the colonists, the government took a hardline attitude toward movements like the Neo-Destour and Istiqlal. Tunisia's Habib Bourguiba was arrested again in 1952, and in 1953 the French removed and exiled Morocco's Sultan Muhammad V, exiling him first to Corsica, and then to Madagascar. However, when the Algerian war for independence broke out, the French realized that they weren't going to be able to hold onto all three Maghreb colonies, so to save Algeria, they abandoned the other two. In 1955 Bourguiba was released, and Muhammad V was allowed to return; both Morocco and Tunisia were declared independent a year later. Then in 1957 Bourguiba removed the last of the beys, since they had been figureheads for three quarters of a century. There was still a Franco-Tunisian dispute over Bizerte, because the French wanted to keep a military base there, so Bourguiba attacked it; a thousand Tunisian lives were lost before the French agreed to leave in 1962. By then, most of Tunisia's 180,000 Europeans had fled the country as well.

Morocco was blessed in that of all North African countries, it was the least affected by imperialism, both by accident and by design. It had been under European rule for only 44 years, and unlike other African and Arab states, its monarchy had existed long before Europeans started meddling in the region, so nobody could call the sultan a puppet of the West. Muhammad V favored left-wing politicians and pursued a radical nationalist foreign policy, to nip in the bud any criticism from those who wanted to replace him with a Nasser-style republic. By contrast, his son Hassan II (1961-99) did not see the need to play such a game, and under him Morocco was one of the most pro-Western states, in both Africa and the Arab world.

Spain didn't make a fuss over its part of Morocco when the French gave up theirs. Within months after French Morocco became independent, the Spaniards withdrew from Spanish Morocco, except for the three ports of Ifni, Ceuta and Melilla. Ifni was returned in 1969, but Spain held onto the territory to the south, the Spanish Sahara, until it provoked a crisis in 1975 (we'll cover that in the next chapter).

This is the end of Part I. Click here to go to Part II.

FOOTNOTES

1. For the other campaigns of World War I, read Chapter 14 of my European history, Chapter 4 of my Russian history and Chapter 15 of my Middle Eastern history.

2. He could do this because of his status as Islam's Caliph (spiritual leader), a title that had technically been his since the events in Chapter 6, footnote #10.

3. In 1917 Blaise Diagne became the Undersecretary of State for the Colonies of Metropolitan France. He was definitely an exception to the rule. The French government had promised full citizenship to any black African who accepted French culture, but nobody was in a hurry to educate the natives for this, because it would mean treating them as equals rather than as conquered peoples. For Moslems it was even worse, because they had to reject Islamic law in favor of French civil law; few were willing to go that far. By 1936, French West Africa had a population of 14 million, of which 80,000 Senegalese and only 2,000 others were French citizens.

4. In 1928, two years before his coronation, Ras Tafari/Haile Selassie put down a rebellion without firing a shot. There was an old Oromo warlord named Balcha Safo who didn't recognize his authority, and Balcha sent an army of 10,000 men to Addis Ababa to challenge the man who would be king. Instead of fighting back with an army of his own, as everyone expected, Ras Tafari invited Balcha to a banquet in his honor. Balcha had heard stories about famous people getting killed or arrested at banquets when they weren't paying attention, so he accepted--very cautiously. He brought 600 men along, and ordered them not to drink so they could guard him.

At the banquet, Ras Tafari was the perfect host, always acting polite and deferential to his guest. Balcha, on the other hand, was rude and constantly made threats, until even his own men were sneaking over to Ras Tafari and apologizing for the boorish behavior of their boss. At the end of the banquet, Ras Tafari sent Balcha off with gun salutes and cheers. Because Ras Tafari had not tried to spring any sort of trap, Balcha was confident that his host was a wimp who could be defeated whenever he liked. But when he reached the spot where he had left his army, it wasn't there. Though Balcha had been doubly careful to protect his person, he had forgotten to protect his army. While he had been entertained at the banquet, Selassie had sent his most trusted official with gold and cash to Balcha's army, and this man bribed the soldiers to hand over their weapons and go away. Ras Tafari also appointed a new governor to run Balcha's province, in place of Balcha. When Balcha tried to go home, he found one army blocking the way and another army following behind him, both of them loyal to Ras Tafari.

Balcha Safo was shamed because he had lost his army without a fight; he returned to Ras Tafari, conceded defeat and became a monk. He stayed in a monastery until Italy invaded Abyssinia, whereupon he tried to rally a force to defend the country, and got killed by Mussolini's troops.

5. The 6th South African Infantry, an inexperienced unit sent to the East Africa campaign, tended to look down on all non-European soldiers until February 12, 1916, when they ran away from a group of pro-German askaris charging with bayonets. However, a nearby Indian unit, the 130th Baluchis, stood their ground and managed to save the machine gun their white colleagues had abandoned. After the battle, the Indians sent the machine gun back to the South Africans on a mule, with a note that read, "With the compliments of the 130th Baluchis. May we request that you no longer refer to our people as coolies."

6. For more details about the development of the Church in Africa, read the "Zulu Zion" section in Chapter 8 of my history of Christianity.

7. Also take note of the fact that Spain's most battle-hardened troops were now stationed in Spanish Morocco. Ten years later, General Francisco Franco would use them to launch the Spanish Civil War.

8. Of the 300,000 soldiers that Italy committed to the campaign, 5,000 were killed, and most of the casualties were not ethnic Italians, but troops from Italy's African colonies. This made Mussolini remark that he wished more Italians had been killed so that people would take the war seriously.

9. "If there ever was an opportunity of striking a decisive blow for a generous cause it was then. The fact that the nerve of the British government was not equal to the occasion, played a part in leading to a more terrible war."--Winston Churchill

10. Mussolini had the largest of Axum's ancient obelisks hauled away as a war trophy in 1937. These structures, raised by pre-Christian Ethiopians to mark royal graves, are at least 1,700 years old, and were probably inspired by Egyptian obelisks, but have a distinctive style of their own. After World War II, Ethiopia called for the return of the 78-foot-tall granite obelisk, but the Italian government dragged its feet for decades, arguing that it wasn't feasible to send the obelisk back, and even claiming that it had been in Rome long enough to become part of Italy's cultural heritage, like "Cleopatra's Needle" in St. Peter's Square. It was finally returned in 2005, after having been sawn into three pieces so a cargo plane could carry it. One old Ethiopian man, who had been a child the last time the obelisk stood in Axum, remarked that he didn't believe the war between Italy and Ethiopia had truly ended until the obelisk returned.

11. Felix Eboué went on to become the governor of all of French Equatorial Africa in 1943. As far as the author knows, he was the first black man to serve as governor of an African colony; but he wasn't an African native; he was born in French Guiana, France's South American colony.

12. However, this meant delaying Hitler's upcoming invasion of Russia, and may have been the main reason why that campaign failed, resulting in the ultimate defeat of Germany. See Chapter 5 of my Russian history for the details.

13. Both sides found it distressingly easy to get lost in the desert. This happened to Rommel in 1941, when he lost track of where he was along the front lines, decided he wouldn't be able to find his way back before nightfall, and chose to spend the night out in the open. The next morning he learned he had spent the night next to a British unit, the 4th Indian Division, but had not yet been detected--so he escaped from what could have been a very embarrassing situation.

14. For two weeks in early June of 1942, 2,000 Free French soldiers held out at Bir Hakeim, against 40,000 Germans and Italians. In the end they had to withdraw to keep up with the retreating British, but nowadays this is counted as the first Free French victory against the Axis (as opposed to them fighting other Frenchmen).