| The Xenophile Historian |

A History of Christianity

Chapter 2: CHRIST CONQUERS CAESAR

300 to 600 A.D.

This chapter covers the following topics:

| Constantine | |

| Controversies and Councils | |

| While Rome Fell | |

| The End of Arianism | |

| The Birth of Monasticism | |

| Go to Page Navigator |

Constantine

Something went very wrong in the Roman Empire around 200 A.D. The imperial throne became available to anyone who had the troops to back him up, and the Praetorian guards started making and unmaking emperors according to who promised them the most gold. Within a period of 50 years (235-285) more than twenty "soldier emperors" rose and fell from the throne, each one taking it by assassinating his predecessor. Meanwhile, barbarians poured across the now poorly guarded borders, and rebels took away whole provinces. The economy also went bad; plagues decimated the cities, and inflation made the money all but worthless. Order and peace returned when yet another general, Diocletian, seized power in 285, but by the time he and his successors were finished the empire they saved was very different from the empire Julius Caesar and Augustus had founded: the empire's capital was no longer Rome, it was Christian, it had at least twice as many bureaucrats, it was often divided in two and it was a lot poorer.

Unlike his predecessors, Diocletian did not pretend to be anything but an absolute monarch. He became the first emperor to wear a crown, rather than the customary laurel wreath, surrounded himself with eunuchs, wore robes of purple and gold silk, carried a scepter, and placed red silk slippers adorned with precious stones on his feet. He also demanded that all people admitted into his presence--including his own family--prostrate themselves and kiss the hem of his robe. All this was meant to make whoever sat on the throne look so impressive that potential usurpers would be scared out of trying to remove him.

Diocletian observed the pagan cult of ancient Rome, so he saw the Christians as a dangerous subversive movement. There were Christians in the imperial bureaucracy and even in Diocletian's own family. The first of his four anti-Christian edicts ordered the destruction of all churches and their holy books. Diocletian showed he meant business on the very day this edict went into effect, by having a church within sight of his palace burned down. The second edict commanded Christian clergymen to sacrifice to pagan gods on pain of death; the third edict extended this order to all Christians. The fourth edict gave additional powers toward the carrying out of the other three.

Diocletian retired in 305. Within a year, the complicated system he had set up for succession broke down, with four generals fighting to become the ruler over the whole empire. One of them, Diocletian's official heir Galerius, had thousands of Christians thrown into dungeons and executed without trials or regard for rank. Among the victims was a bishop named Donatus, who spent six years in jail and was put on the rack nine times; he survived to lead a Novatian-style radical movement that opposed the forgiveness of Christians who had, unlike him, recanted their faith. Six frightful years later, Galerius realized that Christianity was too widespread to be stamped out and his policies were alienating even non-Christian Romans. On his deathbed, he voided Diocletian's edicts, and pleaded with Christians to pray for his salvation.

Most of the soldiers of the day habitually disliked Christians, so to them it seemed natural to continue Diocletian's persecutions. But one of the competing generals, Constantine, felt differently. He saw that Christianity had become so strong and so well organized that it could provide the unity the empire so desperately needed. According to the story, in 311 Constantine was marching to capture Rome when at Milvian Bridge he saw a vision of the initials of Christ (the Greek letters chi and rho, X and P in our alphabet) in front of the sun, surrounded by these words: "In hoc signo vinces" (By this sign conquer). At once he marched his troops into the river, declared them baptized, and ordered them to paint those letters on their shields. When the following battle ended in victory he became a lifelong friend of Christianity. During the next 12 years he succeeded in eliminating his colleagues and for the last 13 years of his life he ruled the empire alone. Finally on his deathbed he was baptized (337).

(This makes his expressed Christianity sound like pure politics, but he may have been playing it safe spiritually. Many Christians in those days delayed baptism for years after they became believers, out of fear that any sin committed after baptism would ruin one's chance for salvation!)

When Constantine legalized Christianity he let himself in for a big building program. The old temples were not suitable for churches, for however imposing they might be on the outside, most of them had room for only a handful of priests on the inside. Christians needed buildings capable of holding a large number of believers at any given time. Up to this point large houses had been the places most frequently used for worship.

The standard Roman design for a large building was the basilica, a three-part structure with a two-story main section (nave) and a single-story hall flanking it on each side. Halls of this type were ideal places for church congregations, so hundreds of them were built in the fourth and fifth centuries.

The basilica normally had a wooden roof. Concrete ceilings were possible, but this meant building massive walls and buttresses to hold them up, which were very expensive. When Constantine decided to build a basilica over the grave of the Apostle Peter he made it big but kept the cost in mind by choosing a wooden roof; he also saved some money by using columns from abandoned pagan temples.

St. Peter's Basilica gave Rome a Christian building on a scale to match the masterpieces of classical antiquity, and despite Constantine's cost-cutting measures, it outlasted most of its rivals. It was only in 1506--by which time the south wall was leaning about 5 feet over from the vertical--that the demolition team came in and began working on the present-day St. Peter's Cathedral.

On one point Diocletian and Constantine held the same views. They saw that the western half of the empire was no longer as important as the eastern half. The West's population was so reduced and scattered in the countryside that the government could not tax it enough to pay for and feed the army. The eastern provinces, on the other hand, with their higher, more urbanized populations, were richer and more easily administered. The East had become the proper place for an emperor to live. Diocletian had lived in Nicomedia, a city in northwest Turkey on the eastern shore of the Sea of Marmara. Constantine moved to the small city of Byzantium on the European shore, which he greatly enlarged and renamed Constantinople.

Constantine's choice for a new capital was a brilliant one. By placing it on the main crossing point between Europe and Asia, he gave the government a commanding position over the trade of both. Moreover, since it was on a peninsula, defenses were superb: it could be protected on three sides by the navy, while the most massive set of walls the Western world had seen was built on the fourth side, making for a city so impregnable that it resisted onslaughts for a thousand years. Officially the fall of Rome is dated at 476, but that was only the western half of the empire; the eastern half (also called the Byzantine Empire) lasted so long that its end in 1453 also marks the end of the Middle Ages.

Controversies and Councils

As the Church converted Constantine, so Constantine also transformed the Church. The Christianity taught by Jesus was a prophetic faith; three hundred years later it had become a priestly one. Jesus did not tell His followers they needed priests, altars, or temples, but now all three of those elements overshadowed everything else. Though Christianity did not become the new state religion just yet, it was clear whose side the emperor was on. Constantine built many new churches and became the Church's prime defender, in ways the Bible had never promoted. His actions discouraged those who followed any other faith, and disagreement with the government on matters of doctrine became grounds for treason; the state now used the same brute force to promote Christianity that had once been used to promote paganism. One could venture to say that in the time of Constantine the devil stopped trying to destroy the Church, walked up the aisle and joined it!

As Christianity came out into the open, so did some critical controversies among the believers. In the third century theologians like Paul of Samosata and Sabellus taught that Jesus was a good man so filled with the Holy Spirit that he turned into God; this point of view, called Sabellianism, saw the unity of God as being so important that they probably did not believe God could be in Heaven while Jesus walked on Earth. A different view was proposed in Constantine's time by Arius, a brilliant clergyman from Alexandria. Arius thought that Jesus could not really be the son of God; instead He was a person who had been created by God at the beginning of time to save men. Alexander, the bishop of Alexandria, excommunicated Arius, and Alexander's successor, Athanasius, argued strongly that Jesus must be the son of God, for if He isn't, His death cannot save us from our sins. That should have ended the matter, but enough of the clergy agreed with Arius that Constantine felt the need to intervene.

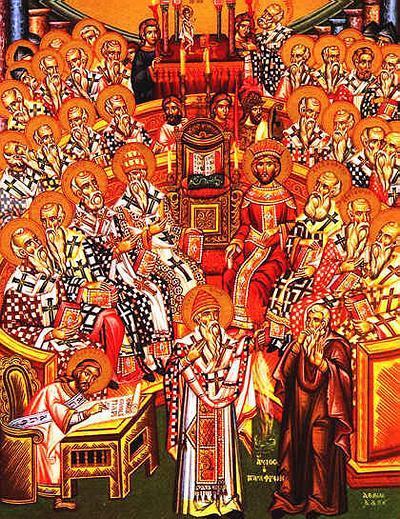

The result was the first great ecumenical (universal) council of bishops, held at Nicaea in 325. Constantine had not yet been baptized, and probably had only a superficial knowledge of what was being discussed, but he presided over the meeting anyway, though most of the speeches must have gone over his head. The view of the moderate (Trinitarian) faction was put down in writing, as the famous Nicene Creed, and Arianism and Sabellianism were condemned as heresies. Since Constantine wanted unity most of all, the council must have looked like a big success to him.

The Council of Nicaea.

But there were more bumps in the road ahead. Arianism refused to go away quietly, because many found it easier to understand than the complicated subject of the Trinity. Constantine's immediate successors preferred Arianism, so they discriminated in favor of the Arians, resulting in Athanasius getting exiled five times between 335 and 366. Then in 361 Constantine's nephew Julian (also known as Julian the Apostate) became emperor and tried to turn back the clock. Julian saw himself as a latter-day Greek philosopher, rejected the Christianity he had been forced to observe previously, and introduced a form of paganism he called Neo-Platonism, which copied the organization and charity of the Church and tried to outdo it in superstition. Anything that hurt the Church was good enough for him; he ended the subsidies that the state had given the Church during the previous generation, ordered the Christians to give back property that had formerly belonged to pagans, and even offered to rebuild the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem (at this point Christians and Jews were no longer on speaking terms with each other). But like Decius, Julian was killed in battle after only two years; his intellectual ideas died with him, and the adoption of any religion besides Christianity by an emperor became unthinkable.

It was under Theodosius I (379-395) that Trinitarian Christianity became the official religion of the empire. The last pagan temples were closed, and a second ecumenical council, held at Constantinople in 381, outlawed Arianism and clearly defined the relationship between God the Father and God the Son. A bishop, Ambrose of Milan, became the most powerful person in the empire, and the first clergyman to successfully coerce a head of state; he made Theodosius do penance publicly for allowing a massacre of civilians in Thessalonica.

A rival of Theodosius in the west, a general named Magnus Maximus ("Great the Greatest"), became the first Christian to execute another for heresy. The victim, Priscillian, was the leader of a strict ascetic movement in Spain. Accused of heretical beliefs and immoral behavior, he was put to death with six associates in 384. He was involved with magic and the occult, but it appears that Priscillian's eccentric beliefs and practices offended Maximus the most. A bishop, Martin of Tours, strongly opposed both the execution and the fact that the trial was conducted by civil leaders who were not members of the clergy. Most Christians were unwilling to go so far as to make the state play the role of executioner for the Church, but this event would foreshadow the later medieval practice of handing over condemned heretics to be put to death by the state.

The Christianization of Rome encouraged Christians in the Middle East to favor Roman policies. Armenia had already proclaimed itself the world's first Christian nation in 303; now this buffer state between Rome and Persia was bound closer to Rome. In Africa Christianity converted the peoples of Abyssinia (Ethiopia) and Nubia (Sudan) in the fifth and sixth centuries respectively, but they lost what little contact they had with the rest of Christendom when the Moslems conquered Egypt in 641.

In the mid-fourth century a brave bishop named Ulfilas, a barbarian raised in Constantinople, travelled to the Visigoths and introduced them to Christianity. By combining Greek and Roman letters with Scandinavian runes, Ulfilas invented a Gothic alphabet, and wrote the Bible in it for his converts, though he prudently omitted the books of 1 & 2 Kings because he felt that would encourage the tribesmen to continue their warlike ways. His teaching later spread to the Ostrogoths and the Vandals, and there lay a major tragedy. Ulfilas was a follower of Arianism, so the Germans he converted became heretics in Roman eyes.

When the Germans began to take over Roman territory, their Arianism became the banner of a proud and very successful minority, fearful of absorption into the mass of Catholics they had subjugated. This attempt to exist as a distinct and superior class was shortsighted, for it continually reminded their subjects that they were ruled by a handful of foreigners. It is no coincidence that the most successful of the German tribes were either those who adopted the faith of the empire's Catholic majority (the Franks), or avoided conversion until Arianism was gone (the Anglo-Saxons).

Now that the controversy over the Trinity was settled, a new storm broke over the relationship between the human and divine components of Jesus. Did Jesus have only one personality that was divine from birth (the Monophysite view)? Did he have two personalities in one body (the Nestorian view)? Or were his two natures at once separate but intermingled? Once again the in-between view was the one the state adopted; at the councils of Ephesus (431) and Chalcedon (451), Nestorianism and Monophysitism were respectively condemned as heresies.

The doctrines behind these controversies are too subtle for many people to understand today, but worth noting because of what formed around them. Before political parties were invented, a dissident religion was used by people to express political opposition. In a time when the natural order seemed to call for one government ruling most of the known world, a modern-style nationalist movement with a slogan like "Freedom for Armenia" would have been unthinkable. But the central power could be indirectly challenged by adopting the local heresy, giving it patriotic overtones. For that reason Nestorianism survived in Syria and Monophysitism gained a passionate following in Egypt, Syria and Armenia. Likewise the emperors felt inclined to reach some compromise with the heretics, since they revealed a discontent with the state that was otherwise inexpressible. The African Donatists, however, were not subtle enough; when they opposed the appointment of a new bishop at Carthage, they crossed the indefinite line between Church and State and brought down on their heads the full weight of the government.

Because Constantinople was the focal point of theological controversies, even the ordinary person in the capital became his own theologian. In 381 St. Gregory of Nyssa wrote in amusement and despair: "Every place in the city is full of theologians--the back alleys and public squares, the streets, the highways--clothes dealers, money changers, and grocers are all theologians . . . If you inquire about the value of your money, some philosopher explains wherein the Son differs from the Father. If you ask the price of bread, your answer is the Father is greater than the Son. If you should want to know whether the bath is ready, you get the pronouncement that the Son was created out of nothing!"

While Rome Fell

Theodosius I was the last emperor who ruled the whole empire. Seeing that his two sons were not up to his job, he divided the empire between them. Nobody after them was very competent either, so this time the division became permanent. The eastern half had the gold to buy off the Huns, Goths, and other barbarian invaders. The West didn't, and the fifth century saw it succumb to waves of barbarian invasions.

One aspect of the Roman Empire survived the fall more or less intact: the Church. For that reason, many of the most important figures of the fifth century were Church leaders, and a few words about them are in order.

1. John Chrysostom (350-407), a reluctant bishop of Constantinople, was the greatest Christian orator of the day. A native of Antioch, he was temperamentally unsuited to life in the imperial capital, and his sermons against the Empress Eudoxia and the corruption around him led to his exile twice. Today he is remembered as an example of piety and courage, and hundreds of his eloquent sermons have survived, which earned him his Greek nickname of Chrysostom ("golden mouth").

2. Jerome (345?-420), an Italian who mastered both Hebrew and Greek, became the scholar who translated the Bible into the Latin text still used by the Catholic Church today, the Vulgate Bible.

3. Augustine of Hippo (354-430) probably did more than anyone else since the first century to put down in writing what Christianity was all about. As a youth he experimented with various religions and philosophies, including Manicheism and Epicureanism, until he was appointed imperial rhetorician in the city of Milan, where the eloquence of Bishop Ambrose convinced him that Christianity could be intelligent and that the Bible was not as barbaric as he originally thought. From 396 until his death he served as a bishop for the North African city of Hippo Regius. Two of his writings have become classics: Confessions, where he tells the story of his search for the truth, and The City of God, where he explains the Christian's duties as a citizen of this world and a citizen of the Kingdom of God. He also wrote against the heresies of his day, like the Donatists, and was one of the first Christians to advocate torture as a tool to make heretics repent.

4. Leo I, also known as Leo the Great, was bishop of Rome from 440 to 461. A key spokesman in the controversy concerning the person of Christ, he proved to be the most powerful leader the Roman Church had seen up to this point. He also introduced the Petrine theory, which claimed that the Apostle Peter was the first bishop of Rome. Not long after that, bishops of Rome began to call themselves popes, meaning "papa". Thus, just like Israel once called for a human king to lead it, now the Church chose to have an earthly king, rather than wait upon the Lord for guidance.

Finally, it should be noted that when Attila the Hun invaded Italy in 452, it was Leo I, rather than the emperor, who personally met with Attila and persuaded him to spare Rome.

5. Patrick (389-461) Originally a citizen of Roman Britain, Patrick was kidnaped by pirates and sold as a slave in Ireland at the age of sixteen. After six years of service as a shepherd he escaped back to the empire, but in a dream he heard the voice of the Irish calling him back, so in 432 he came back, founded several monasteries, and devoted the rest of his life to getting Christianity started in Ireland. The rest of the information we have on him is pure legend, but the Celtic Christian Church he founded preserved both civilization and Christianity after Anglo-Saxon barbarians obliterated them from most of neighboring Britain.

The End of Arianism

Of all the various barbarians tribes that divided the Western Roman Empire between them, the most successful were the Franks, who settled in northern Gaul (henceforth named France). Clovis became king of the Franks in 481, when he was only fifteen years old. At first he was a fine example of a barbarian; brutal, ignorant, and totally amoral, he split skulls, stole treasure, and collected concubines with glee. He was successful not only because he was a talented military leader, but also because under him the Franks became Catholics. As noted previously, the other barbarians were either pagans or Arian Christians, a never-ending source of friction between them and their Catholic subjects. The Catholic bishops looked for a barbarian chief who would become their champion, and had a very skimpy selection of candidates to choose from. Thus, when Clovis won battle after battle they decided that he was their man, despite his personal life.

Clovis listened to what the bishops had to say with interest, and may have seen the advantages of joining the same faith that the ordinary person practiced. He became an even better listener when he chose a Catholic princess, Clothilde of Burgundy, as his bride. With the encouragement of both the bishops and the queen, Clovis was persuaded to accept baptism. The ceremony was performed at Rheims in 496, after which Clovis was followed to the font by 3,000 warriors.

There is no evidence that Clovis' spiritual life or moral character improved much after his conversion, but the fact that it happened caused the Catholics living under other barbarian rulers to welcome him as a liberator, a second Constantine. A bishop in Burgundy, Avitus of Vienne, voiced his sympathies boldly in a letter to Clovis congratulating his baptism: "Your faith is our triumph. Every battle you fight is a victory for us." The other Germanic peoples learned from the example and success of Clovis and gradually switched from Arianism to Catholicism; first the Burgundians (516), then the Visigoths in Spain (589), and finally the Lombards in Italy (653). In the sixth century the other practitioners of Arianism, the Vandals and the Ostrogoths, had been eliminated by the Eastern Roman Empire's conquests, so the seventh century saw the restoration of the Church's unity.

The Birth of Monasticism

Ascetics turn up in all religious movements and, though more prominent in Oriental religions like Buddhism, they have always been present in Christianity. The first such ascetic on record was St. Anthony (256-356), an Egyptian who, like John the Baptist, spent most of his life as a lonely hermit in the desert, devoting his time to praying, studying, and doing the little bit of manual work needed to earn a living. He may have been trying to "get away from it all," but he became famous, and a steady stream of those who admired him and those who were simply curious came to visit him. His example inspired many other "desert fathers" to move into any hut, cave or abandoned building that happened to be away from society. This soon led to the hermit colony and in 320 another Egyptian, Pachomius (290-346), established rules, making his hermit colony the first monastery. By the end of the fourth century monasteries were commonplace in the Eastern Roman Empire, less so in the West because it was harder for the poor western provinces to pay for the upkeep of the monks. Individual hermits were also more common in the east, the most famous of these being St. Simeon the Stylite (390-459), who practiced an extreme form of disciplined living by erecting a sixty-foot high pillar in Syria and living on top of it for the last 36 years of his life.

Western monasticism began its reform of the Church in the sixth century, when St. Benedict of Nursia founded a new Monastery at Monte Cassino, a lonely hilltop between Rome and Naples. At first he lived like the holy hermits of the East, staying in a cave overlooking a stream; its location was so inaccessible that food had to be lowered to him on a rope by those who came to see him. He attracted a lot of visitors during the three years he spent there, but eventually came to the conclusion that self-denial by itself is not the way to salvation. Afterwards, he preached strict rules to live by, but they were meant to help man get along better with his fellow man, not to mortify the flesh. For example, when one hermit invented a new form of saintliness by chaining himself to a rock in a cave, Benedict sent him this message: "Break thy chain, for the true servant of God is chained not to rocks by iron, but to righteousness by Christ."

From his own experience Benedict knew that only a few people are suited to live the disciplined life without direction, so he organized his monastery on a fully communal basis, and put down the rules for it in a remarkable book called A Little Rule for Beginners. The book outlined a complete social system that actually worked; the monks were required to balance their prayers with manual labor in farming or crafts, so that the monastery fed and maintained itself, rather than depending on contributions like the ones in the Eastern Roman Empire did. The monks elected their own governing abbot, who was answerable only to the pope, and to keep stability, each monk took an additional vow (besides the usual ones for poverty, celibacy and obedience) in which he promised to remain in the monastery until death, unless given special permission to leave.

The Benedictine order was such a success that it quickly replaced all others in the West, including the zealous communities of Ireland. They became islands of stability in a troubled world, and attracted the commerce and scholarship of the day. Thus despite their vows, the Benedictine monks grew rich and powerful precisely because the politics of the secular world didn't get in the way. And at the end of the sixth century one of them would become Pope Gregory I.

Support this site!

PAGE NAVIGATOR

A History of Christianity

|

Other History Papers |

Beyond History

|