| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of Latin America and the Caribbean

Chapter 5: Uncle Sam's Backyard, Part IV

1889 to 1959

This chapter is divided into five parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| The Big Picture | |

| Cuba Libre! | |

| Costa Rica: King Banana | |

| The War of a Thousand Days | |

| The First US Occupation | |

| Mt. Pelée Kills St. Pierre | |

| The Panama Canal | |

| Peru: The Aristocratic Republic | |

| Venezuela: The Tyrant of the Andes | |

| Colombia: The Conservative Republic | |

| The Mexican Revolution, Phase 1: Conservatives vs. Liberals |

Part II

| Uruguay's Welfare State | |

| The United States Occupation of Haiti | |

| Argentina: The Radicals In the Saddle | |

| The Mexican Revolution, Phase 2: Moderates vs. Radicals | |

| Independent Cuba: The Early Years | |

| Guatemala: A Cultured Brute and a Napoleon | |

| Brazil: The Old Republic | |

| Honduras: La Republica de los Bananas | |

| Chile: Parliamentary and Presidential Republics |

Part III

| Ecuador: The Leftover Country | |

| The Mexican Revolution, Phase 3: Coming Full Circle | |

| The Dominican Dictator | |

| The Chaco War | |

| El Salvador: The Coffee Republic | |

| Uruguay: The Terra Era | |

| The Somoza Dynasty, Act One | |

| Panama: The Bisected Protectorate |

Part IV

Part V

| Cuba: The Auténticos and the Second Batistato | |

| Puerto Rico: "Candy-Coated Colonialism?" | |

| The Ten Years of Spring | |

| After the Mahogany Rush | |

| Getúlio Vargas, Back for an Encore | |

| The Perón Decade | |

| La Violencia | |

| Venezuela: Back In the Barracks | |

| A Word on the Guianas | |

| The Cuban Revolution |

The Infamous Decade

Unlike other Latin American countries (e.g., Bolivia), Argentina did not have a tradition of the military getting involved in politics; the last time they decided who would be president was in 1861. In 1930 they had no plans beyond getting rid of Yrigoyen; all they wanted was to make sure Argentina made orderly progress. Therefore, they first decided that they needed to keep a balance of power between the landowners, middle class, and urban workers. This marked the beginning of six decades of military involvement in Argentinian life.

Present-day Argentines refer to the thirteen years after the coup as the "Infamous Decade" (1930-43), because it was a time with a lousy economy, and bomb attacks and shootings by radical anarchists. This gave the military a reason to stick around and defend the government, so this was also a time of electoral fraud, persecution of political opposition, and widespread corruption.

The first president after Yrigoyen, General José Félix Uriburu, wanted a corporatist government with strong leadership, like the fascist regimes of Italy and Portugal. He cracked down brutally on anarchists, communists and other leftists, resulting in 2,000 illegal executions. This was too much for the conservative backers of the coup, so when elections were held in November 1931, they went with a more moderate general, Agustin P. Justo. Justo formed a coalition of conservatives and anti-Yrigoyen Radicals called the Concordancia, but still the election was heavily fraudulent. Although Concordancia governments ruled until 1943, they never were legitimate in the eyes of the people.

Of course recovering from the Great Depression was a priority in the 1930s, so Justo's program for Argentina including balancing the budget, servicing the foreign debt and boosting exports. The latter led to Justo's worst decision, signing the Roca-Runciman Treaty with the British in 1933. When the United Kingdom reduced imports during the Depression, it showed preference to the Commonwealth nations; it cut back on beef from Argentina but not from South Africa and Australia. The Roca-Runciman Treaty guaranteed that Britain would import no less than 390,000 tons of refrigerated beef a year (the 1932 level), in return for a reduction in tariffs on British goods and some other trade concessions. However, the British could still purchase more beef from elsewhere, so the treaty benefitted the British economy and the rich estancieros, but not Argentina as a whole. Opponents of the treaty declared that Britain had gotten the better part of the deal, and denounced a century of British meddling in Argentine affairs, from the occupation of the Falkland Islands to preventing the annexation of Uruguay when it looked like that country would become part of the Argentine state (see Chapter 3).

After another rigged election, Justo was succeeded in 1938 by Roberto María Ortiz. However, Ortiz was seriously ill with diabetes and handed over power to his vice president, Ramón Castillo, in 1940, though he remained in office until his death in 1942; then Castillo took over in name. Their co-presidency oversaw the beginning of World War II, and many Argentines wanted to sit out this war, the way they had sat out World War I. The military especially did not want to go to war. After studying Prussian/German military history in school, the soldiers came to admire Germany's military skill, if not German ideology. And after Germany's invasion of the USSR brought the Communists into the Allied camp, the soldiers definitely did not want to join the Allies. Meanwhile, the war cut off trade across the Atlantic (again), but this time Argentine industry succeeded in making the goods that could no longer be imported, resulting in a small economic boost.

The United States entered the war in 1941, and began promoting a treaty that called for a Pan-American alliance against the Axis powers. Argentina resisted US pressure at first, but grew alarmed at the arms Washington was sending to its old rival, Brazil, because Brazil willingly joined the alliance.

Castillo's term was due to end in 1944, and in early 1943 he looked for someone to back as his successor. But everyone was tired of the Concordancia; the Radicals gained control over Parliament, and the military did not want to support the candidate Castillo picked, because they knew he could only win by stealing the election. Deciding that the country needed another change, a group of officers called the United Officer's Group (GOU) staged another coup on June 4, 1943, replacing Castillo with a military junta.

Getúlio Vargas and the Estado Nôvo

Vargas was a little man with two characteristics that don't always go together--efficiency and likeability. Coming from Brazil's cattle ranching state, Rio Grande do Sul, he was the Portuguese version of a gaucho. A good description of him comes to us from a US journalist, who wrote in 1942 that Vargas was "able, friendly, slippery . . . He seldom disagrees with anyone. He may delay or equivocate, but he almost never says an outright No. He has very few enemies, and he seldom bears grudges. No dictator is so little vengeful."(69)

At first Vargas only wanted to free Brazil from the grip the oligarchies and São Paulo had on the country, so he spent the first half of the 1930s breaking up the "good old boy network" and replacing it with his own. He replaced all state governors with his own men, called "interventors," and gave them orders to reduce the size of state militias and reorganize local political machines to make them pro-Vargas. The militia of São Paulo revolted in 1932, and because they were the strongest state militia (50,000 soldiers vs. 100,000 sent against them), it took three months to bring them to heel, at a cost of 3,000 lives. However, when elections were held the following year, Vargas gave in to one of São Paulo's demands, allowing them to elect their delegates to the constitutional convention he was about to hold. The same election turned Vargas into a real president, by electing him to a four-year term.

The new constitution went into effect in 1934. Its most unusual feature was the makeup of the legislature: besides 214 representatives from geographic locations (the usual pattern), there were also forty representatives of social classes, reflecting the interest Vargas had in corporatist-style government. In 1935 there was another rebellion, this time from the Communist Party and its left-wing allies; it ended with the capture and imprisonment of the previously mentioned Luís Carlos Prestes.

Vargas' term as president was scheduled to end in 1937, and the constitution did not allow him to run again. As elections drew close, a general close to Vargas revealed another Communist plot to overthrow the government. It was later proven false, but Vargas used it as an excuse to declare a national emergency, cancel the elections, and suspend the constitution. In its place he declared the establishment of the Estado Nôvo (New State), and introduced another constitution that gave him absolute power, creating a government modeled on the corporatist dictatorship of Antonio Salazar in Portugal.

Although Vargas banned political parties, imprisoned political opponents and censored artists and the press, many liked him. The "father" of Brazil's workers, he created Brazil's minimum wage in 1938, and like other heads of state during the 1930s, he introduced "economic stimulus packages" to hasten recovery from the Depression. Each year he timed new labor laws so that they would be introduced on May 1, the international workers' holiday.(70) In place of political parties, he created a National Economic Council, and allowed everyone to express their opinions there; bureaucrats, industrialists and the military liked seeing the economy guided this way. Finally, to get Brazil out of the boom-and-bust cycles caused by dependence on exports like coffee, he made industrialization a priority, with emphasis on steel, mining, oil, electricity, chemicals, motor vehicles and light aircraft.

As a populist dictator, Vargas admired the fascist regimes that arose in Europe during the Depression years. He even played off the United States against Nazi Germany for a while, to see which country would give Brazil more aid. It was the US, of course, and some believe a mysterious $20 million investment from the Americans in 1942 made him decide to enter World War II on the side of the Allies. Brazil was the only South American country to actively participate in any war zones; the Brazilian navy helped the American and British fleets by patrolling the south Atlantic, and 25,700 Brazilian men and women fought on the Italian front from September 1944 to May 1945.

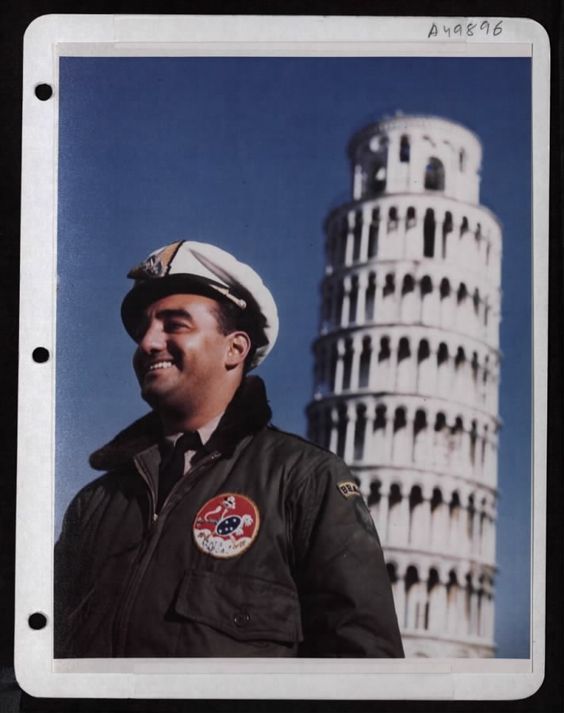

A Brazilian WW2-era pilot, with the Leaning Tower of Pisa behind him.

The second term given to Vargas by the constitution was due to expire in 1943. When 1943 arrived Vargas announced that because of the emergency caused by World War II, he must stay in office, but as soon as possible there would be a new election. In 1944 he made a similar announcement. Obviously he wasn't practicing what he preached, fighting for democracy in Europe while running a fascist-style state at home. When the war ended he could not postpone elections any longer, so he scheduled them for December 2, 1945, made political parties legal again, formed two parties to promote himself, and released the Communist leader, Luís Carlos Prestes, from jail. A grass-roots movement also appeared, called the Queremistas because its members kept saying "Queremos Getúlio" ("We want Getúlio"); many thought Vargas started this movement, to make people think the vast majority of the population was on his side. Most disturbing, Vargas was required by law to resign before the elections, so the incumbent would not have an advantage over the other candidates, but he showed no signs of stepping down as 1945 went on.

When Vargas appointed his brother chief of police in Rio de Janeiro, the military acted. A delegation of military men confronted Vargas in October 1945, to tell him that his time as president was up, and that he would not be allowed to run for president in the next election. Vargas thought briefly about fighting to stay, and then resigned. We said earlier that Vargas didn't carry a grudge, and he showed it here by endorsing Eurico Gaspar Dutra, one of the generals who told him to leave; Dutra won the election and got Vargas' job.

Despite his fall from grace, Vargas remained popular. During the next four years he was nominated for senator and elected to that job, though he did not seek it. Overall he acted like he was retired from politics, spending most of his time on his ranch in Rio Grande do Sul.

Colombia: "The Revolution On the March"

Colombia's first president of the 1930s, Enrique Olaya Herrera, was kept from doing much by a lack of money. The price of coffee had fallen to one third of what it had been in 1928, US banks stopped making loans, and the world's developed countries could not help while they were stuck in the Great Depression. However, Olaya managed to enact limited educational reforms, and though Peruvian troops occupied Leticia, a disputed town in the southeast corner of the country, in 1932, Colombia got it back in the peace settlement ending the "Leticia Incident"; that is covered in the section on Peru.

Some Liberal Party members, including the previously mentioned Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, were so disappointed that they formed a revolutionary movement, the Revolutionary Leftist National Union. It didn't last long, though, because the Liberal president elected in 1934, Alfonso López Pumarejo, was more to their liking. The López administration implemented extensive reforms in agriculture and education, and strict enforcement of income and inheritance taxes; he called this program the "Revolution on the March." Land reform was considered especially important, because Colombia could no longer grow enough food to feed its urban population. The 1936 agrarian reform law allowed the expropriation of private property, in order to promote "social interest." Under this, lands that were not being exploited using modern land management techniques would revert to the state, though the owners of the big farms were allowed ten years to make them more efficient. In addition, peasants could no longer pay their rent in labor or with goods instead of cash, a move that modernized the rural economy. Finally, the law confirmed the property titles of the great landowners, but it also made it harder to evict squatters that had improved unused public or private land. For urban workers, Congress passed laws establishing a minimum wage, an eight-hour day and a forty-eight-hour work week, paid vacations and holidays, banned strikebreakers, and established a special tribunal to handle labor disputes.

The reforms of the the López administration helped in the recovery from the Depression, and when combined with the protectionist measures of the Conservative era, they caused a surge in industrialization. Still, they were bitterly attacked by opponents of López Pumarejo, to the point that in 1936 he announced a "pause" in reform. The pause continued for the rest of his term, and because the next president, Eduardo Santos Montejo (1938-42), was a moderate, only a few changes took place under the Santos administration, like a reduction of taxes on imported machinery that industry needed, and the removal of education from Church control. This caused a split in the Liberal Party between the moderates and reformers; chief among the reformers was Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, now the mayor of Bogotá.

Santos was succeeded by López Pumarejo, who won the 1942 election. I have written elsewhere that when presidents are re-elected, the second term usually does not go as well as the first term, and that was the case here. He had difficulty promoting reform because of strong Conservative opposition and divided Liberals. In addition, he spent six months in the United States to take care of his sick wife, and no reforms were passed while he was away.

López Pumarejo's second term began during World War II, and in 1943 Colombia entered the war on the Allies' side. Colombia did not send any troops overseas, but its navy helped the Americans and British to fight U-boats in the Caribbean. Unfortunately, the war also caused an unbalanced budget, unstable foreign trade, lowered coffee prices, and raised import prices.

Laureano Gómez, the Conservative Party leader, was strongly against Colombia's involvement in the war, and his personal attacks on the president and his family were so offensive that Gómez was imprisoned in 1944, causing street fighting in Bogotá. The same year saw López Pumarejo and part of his Cabinet detained for a few days by officers staging an unsuccessful coup; most of the army stayed loyal to the government and constitution, though. In 1946 the divided Liberals ran two presidential candidates, Gabriel Turbay for the moderates, and Gaitán for the radicals; this allowed the Conservative candidate, Mariano Ospina Pérez, to win with 42 percent of the vote.

The Battle of the River Plate

The only Latin American battle of World War II was fought in Uruguayan waters. Germany was forced to scuttle its fleet at the end of World War I, and because the Germans only began to build a new fleet in the 1930s, they could not challenge the British surface fleet for mastery of the Atlantic. What they could do was use their submarines ("U-boats") and heavy cruisers ("pocket battleships") as raiders against British shipping. The most successful of the pocket battleships was the Graf Spee.

Even before the war had begun, the Graf Spee sailed from Germany, and over a three-month period (September-December 1939) it sank nine British merchantmen. Then it sailed for the Rio de la Plata, with the intention of making attacks on the British shipping lane that ended there. Instead, on December 13, 1939, it met three British cruisers that could fight back: the Exeter, Ajax and Achilles. Even with 3:1 odds against it, the Graf Spee still outgunned the other ships, and managed to damage all of them in the "Battle of the River Plate." But instead of sinking his opponents, the Graf Spee's captain, Hans Langsdorff, broke off and took refuge in the port of Montevideo, where he hoped to make repairs to his own ship. Uruguay was a neutral country, and the Uruguayan government gave him 72 hours to leave. Langsdorff incorrectly thought that the British ships had reinforcements, making escape impossible, so when time ran out, he scuttled his ship; the Graf Spee sailed out of Montevideo's harbor and suddenly blew up. Captain Langsdorff committed suicide, too; being a naval veteran of the last war, he wrapped himself in an imperial German flag (not a more up-to-date Nazi flag) before shooting himself. 1,150 surviving German crewmen were interned by Uruguay and Argentina; many of them liked South America enough to stay after the war ended.

As the war went on, Baldomir had second thoughts about fraternizing with the enemy of Uruguay's biggest trading partners. In 1940 he gave the United States permission to build bases in Uruguay; in 1942 he severed diplomatic relations with all Axis countries. This was opposed by Herrera and the Blancos, who wanted the country to stay neutral, so in 1941 Baldomir forced the three Blanco ministers in his cabinet to resign; then in 1942 he dissolved the General Assembly and replaced it with a body called the Council of State, whose members were all Colorados. While this looked like another coup, it did not come with arrests, deportations, or the closing of newspapers, and was actually a step in the overturning of the 1933 coup and its constitution, which Baldomir now considered a liability.

In the 1942 election, the Colorado candidate, Juan José Amézaga, was elected as the next president (1943-47). Another constitution was put to a plebiscite and passed with 77 percent of the vote. This time the general assembly was restored, and no part of the government (Cabinet, Senate, state-run coporations) was required to share power/membership between two parties, the way the 1934 constitution had ordered.

Bolivia: Contending Ideologies

For Bolivia, losing the Chaco War meant several more years of instability.(71) Colonel David Toro Ruilova, the officer who took over in 1936, wanted a system he called "military socialism"; under this, there would be social and economic justice, and the government would control the natural resources. To get civilian support for this program, Toro picked a print worker to be Bolivia's first labor secretary, nationalized the holdings of Standard Oil without compensation, created a state-owned firm in place of Standard Oil (Yacimientos Petroliferos Fiscales Bolivianos, or YPFB), and called for a constitutional convention, one where the delegates would represent all political parties and the labor movement.

All this sounds ambitious, but for some radical officers it wasn't enough, so in 1937 they supported a coup by Colonel Germán Busch Becerra to replace Toro. In the following year Busch introduced a new constitution, which favored the common good over private property (what we call "eminent domain"), allowed government intervention in social and economic relations, recognized the Indian communities and introduced the country's first labor code. Then Busch became the first president to challenge the mine owners by issuing a decree that would prevent the mining companies from removing capital from the country. If all this had worked as planned, Bolivia would have become the first Latin American country with a modern-style totalitarian dictatorship.(72) But nothing Busch did generated much support from civilians or the military, and his policies alienated conservatives. Frustrated by his inability to bring about change, Busch committed suicide in 1939. The main result of these two military socialist regimes was that they led to the rise of new political groups: leftists whose expectations were raised by what Toro and Busch did, and disappointed when they failed to deliver; and conservatives who joined forces to stop the growth of the left.

The next elected government, led by General Enrique Peñaranda Castillo, was more moderate; it even paid Standard Oil for the assets seized in 1936. This government was a coalition of the Liberals and two factions of the Republicans. Nevertheless, the radicals did not disappear, and they had several parties representing them in Congress: the Trotskyite Revolutionary Workers Party (POR), the Bolivian Socialist Falange (FSB, modeled after the Phalangists in Spain), and the Leftist Revolutionary Party (PIR), formed from several Marxist groups. The most important of these groups was the Nationalist Revolutionary Movement (MNR), founded in 1941 and led by Víctor Paz Estenssoro, a professor of economics. This was the first party to have widespread support in Bolivian history; its membership included intellectuals, white-collar and blue-collar workers.

The MNR's platform called for the nationalization of all of Bolivia's natural resources and far-reaching social reforms. Thus, among the congressional opposition, it took the lead in denouncing Peñaranda's close cooperation with the United States. It also investigated the army's 1942 massacre of unarmed striking miners and their families at a mine in Catavi. Some reform-minded army officers approved of the MNR's actions, and they teamed up with the MNR to overthrow the Peñaranda regime in 1943.

Major Gualberto Villarroel López became the new president, and three MNR members joined his cabinet (Paz Estenssoro served as minister of finance). Villarroel's government emphasized that it would continue the reforms that Toro and Busch had started. They started by raising the salaries of miners, but that got the miners to support the MNR, not Villaroel. In 1945 the government created the National Indigenous Congress to discuss the problems in the countryside and to improve the situation of the peasants. However, conservative opposition kept most of the social legislation from going into effect, and terrorists murdered some opponents of the government. Against this backdrop, rivalry between the MNR and the military tore the government apart. In 1946 mobs of students, teachers, and workers seized arms from the arsenal and moved to the presidential palace. They captured Villarroel, shot him, and hung his body from a lamppost in the main square, while the army stayed put in the barracks. The MNR leadership fled to Argentina, and spent the next six years (1946-52, a time present-day Bolivians call the "Sexenio") organizing.

An interim junta ruled until elections could be held in 1947. The newly elected president, Enrique Hertzog Garaizabal, formed a coalition cabinet that included the great landlords, mine owners and the PIR. Unfortunately, this attempt to burn the candle at both ends didn't work; the PIR was discredited for allying itself with conservatives. The workers, especially the miners, grew more radical, and the government responded with repressive measures; in 1949 it brutally suppressed another uprising in Catavi. 1949 also saw a coup attempt, led by the MNR, that turned into a four-month civil war; although it gained control of most of the cities and forced President Hertzog to resign, it failed to capture La Paz, and the vice president, Mamerto Urriolagoitía Harriague, completed Hertzog's term in office.

Next, the MNR tried to take over legally. In the presidential election of 1951, the MNR won with a clear plurality. The outgoing president, however, refused to hand over power to the leftists, and persuaded the military to install a junta instead. They got away with it, but only for a year, because of Bolivia's deteriorating economy. The tin industry had not recovered from the Great Depression; ore production at the mines was down, due to depleted veins, and tin prices on the world market were still low. The agricultural sector was in bad shape, too, requiring more food imports to feed the population, and high government spending resulted in high inflation. Under these conditions, more social unrest was inevitable. On April 9, 1952, with the support of a friendly junta member, the MNR launched a rebellion in La Paz by seizing arsenals and distributing arms to civilians. Armed miners marched on La Paz and blocked troops coming to defend the city.(73) After three days of fighting and the loss of 600 lives, the army surrendered. Paz Estenssoro was called back from exile to assume the presidency, beginning what is now called Bolivia's "National Revolution."

Cuba: Batista's First Reign

Following the resignation of Gerard Machado, the presidency was offered to Carlos Manuel de Céspedes (the son of the Carlos Manuel de Céspedes in Chapter 4). He lasted for three weeks, and then was overthrown in a coup called the Revolt of the Sergeants, because it was led by a group of non-commissioned officers, of which the most important was Sergeant Fulgencio Batista y Zaldivar. The sergeants set up a provisional government headed by a five-man commission; nowadays it is called the Pentarchy of 1933. That lasted for five days, because the commission members came from different political parties and could not reach agreement on anything, so the main revolutionary group, the Student Directory, forced all but one of them to resign. The one they kept was Dr. Ramón Grau San Martín, a popular physician, university professor and a long-time opponent of Machado. Grau became president; the other two important figures were Antonio Guiteras Holmes, leader of the Student Directory, and Batista, who was now promoted to colonel and became the Army Chief of Staff.

The Grau government did not last much longer--just 100 days (September 1933-January 1934)--but what it got done was impressive. The first and most important thing they did was repeal the Platt Amendment.(74) For the first time in history, Cuba was governed by people who did not take orders from either Spain or the United States. The social legislation passed gave women the right to vote, established an eight-hour work day, gave cane workers a minimum wage, created a Ministry of Labor, promised to give peasants legal titles to their lands, and a law required that 50 per cent of all workers in agriculture, commerce and industry be Cuban citizens (that ended the practice of bringing in cheap labor from other Caribbean islands).

However, the Grau government soon found itself with a problem all politicians have--how do you please everybody? The Student Directory and the Communist Party thought the social legislation did not go far enough; moderates thought Grau had gone too far; conservatives did not like the reforms at all. The United States refused to recognize the Grau government because it did not make payments on loans owned to Chase National Bank, and seized two mills belonging to the Cuban-American Sugar Company. The United States secretly maneuvered with Batista, forcing Grau to resign so that a new government could be set up that Washington found more acceptable. Six presidents quickly rose and fell after Grau; the only one who lasted more than a year was the last one, Federico Laredo Brú (1936-40). All of them were controlled by Batista, who used his position as commander of the armed forces to make himself the most powerful man in the country. Although he did not become president until 1940, most historians consider him to be the real ruler of Cuba from 1933 onward.

The Brú administration held free elections in 1940. At this point, Fulgencio Batista was extremely popular among the masses, because of all that he had done in the 1930s, and because he had recently courted the support of left-wing organizations. Batista and former President Grau ran in the 1940 elections, and a "Democratic Socialist" coalition (which included labor unions and the Communist Party) backed Batista. Grau's party did best in the House of Representatives, but the Democratic Socialists won in the Senate and Batista won the presidency.(75)

Batista's official term as president coincided with World War II. Cuba acted as a reliable US ally, declaring war on Japan on December 9, 1941, and then on Germany and Italy two days later. When he visited Washington in December 1942, Batista said that Latin America would go to war with Francisco Franco's Spain, if necessary, because Franco was a fascist, too. As it did during World War I, Cuba enjoyed another economic boom with sugar, shipping it to countries that could no longer produce their own. In 1944, sugar production finally returned to levels reached in the 1920s. And the boom continued after the war. In 1946, the United States bought the entire sugar harvest for 3.7¢ a pound, to use in its program to rebuild Europe (the Marshall Plan). Then during the Korean War, demand for sugar caused the price to reach 5¢ a pound. But then the high price encouraged other sugar producing nations, especially the Philippines, to grow more sugar, so a glut replaced the wartime shortage and prices fell again.

Venezuela In Transition

When Venezuelans learned that the old tyrant, Juan Vicente Gómez, was dead, they went on a rampage, looting and destroying the houses of his family and collaborators (and killing those folks if they happened to be inside). At Lake Maracaibo the mob threatened to set fire to the oil wells, prompting foreign workers to flee with their wives and children. However, this would not be a civil war, like what Mexico experienced when the rule of Porfirio Diaz ended. Instead, the military and the landowners quickly regained control, making sure that the now-vital oil industry was safe. Because of them, the years from 1935 to 1958 would not see a social revolution, but a generation-long transition to democratic rule.

Because everyone in the government at this point had been appointed by Gómez, his will would be carried out for a little while. For the next president, the military chose his Minister of War, José Eleazar López Contreras. López served the last six months of Gómez's term, and then Congress elected him to his own five-year term, so he was in office from 1935 to 1941.(76)

López realized he needed to eliminate the worst abuses of the previous regime, or there would be more riots. For that reason, he freed political prisoners and allowed exiles to return. The latter formed Venezuela's first political parties and labor unions. But when the unions staged a successful general strike in June 1936, López reversed his stand, figuring that the country had all the reform it could take. In November the left-wing parties decided to merge to form the National Democratic Party (PDN); López refused to give them legal recognition and brutally suppressed an oil workers' strike a month later. Then in 1937 the regime outlawed the unions and nearly all political opposition. After that, López spent the rest of his term on economic reforms (e.g., establishing banks and opening new oil fields), because those were far less controversial.

In 1941, Congress stuck to the pattern set previously and again picked the Minister of War, Isaías Medina Angarita, to become the next president. It would not be business as usual, though, for Medina was more willing to relax the military's grip on the nation than López had been. The PDN was legalized, it immediately changed its name to Democratic Action (AD), and it became a vocal minority in local governments and Congress (Medina allowed congressional elections in January 1943). Medina responded by creating a political party for those currently in charge, the Venezuelan Democratic Party (PDV), and it won a legitimate victory in the next congressional elections (1944). Because Venezuelan presidents were indirectly elected by Congress, it looked like Medina's successor would be hand-picked by him.

Medina astonished the country when he chose Diógenes Escalante, the ambassador to the United States, as the next presidential candidate; Escalante was a liberal civilian, not a military man. Delighted, the AD agreed to support Escalante; opposition instead came the right wing of Medina's party, which wanted former President López nominated for a second term. Shortly after that, though, Escalante fell ill and could not run, and the next candidate Medina chose was seen as a puppet of his, so now both sides of the political aisle were offended. On October 18, 1945, several junior military officers working with the AD ousted Medina in a coup, and installed the AD leader, Rómulo Ernesto Betancourt Bello, in his place.

At first Betancourt appointed a seven-man junta, with four AD members, two officers, and one independent. All officers who had held a rank above major before the 1945 coup were retired. Universal suffrage for men and women over eighteen was passed, and all political parties were legalized. Congressional elections were held in 1946 and 1947, and both were overwhelming victories for the AD; 79 percent of the vote in 1946, 73 percent in 1947. This gave Betancourt and his partners the green light to go ahead with their plans for the country. The foremost items on their agenda were a new constitution, raising taxes on the oil industry's profits to 50 percent, and to expand/regulate education (previously the schools had been run by the Church). In February 1948, the AD candidate, Rómulo Ángel del Monte Carmelo Gallegos Freire (Rómulo Gallegos for short) was elected president.(77)

The AD's inexperienced politicians did not realize that their program to turn Venezuela into a welfare state was moving too fast, for those who disagreed with them. Oil companies were upset at the new taxes, landowners were outraged by a bill that promised to distribute unused land to the peasants, and the military was alienated by cuts in defense spending and a reduction in the number of military men in the cabinet. The inevitable coup came in November, just nine months after the inauguration of Gallegos; both Betancourt and Gallegos went into exile again.

The Rise of Juan Perón

The first leader of the 1943 Argentine junta, Arturo Rawson, promised the British embassy that he would declare war on the Axis in three days, so he was removed by the rest of the junta on June 6, only two days after the coup. The next president was Pedro Pablo Ramirez, but a minor member of the GOU, Colonel Juan Domingo

Perón, soon moved to the forefront. First he was an assistant to the new Secretary of War, then he became Minister of Labor, getting that job because nobody else wanted it.

Juan Perón (1895-1974) is both the most loved and the most hated figure in Argentina's history. He rose to the top because unlike the other members of the GOU junta, he had a vision for the future. In 1938-39 he served as a military attaché to Mussolini's Italy, and while overseas he studied the governments of Europe to see what worked best. He decided that in the twentieth century, it is better to be a populist than an elitist, so a new type of caudillo was needed, one who, in the Spanish macho tradition, was still a real man, but like the political bosses of big US cities, he would be friends with the middle and working classes. He also believed, from watching Mussolini, that a leader needed to stage spectacles for his subjects, but a totalitarian government like Nazi Germany was too much; for Perón the happy medium was a European-style social democracy with a strong leader in charge of it. By combining his populism with a strong dose of nationalism and a fondness for flashy uniforms, Perón attracted people from both the right and left ends of the political spectrum, but this inconsistent ideology (we will call it Peronism after this) also led to feuding among Perón's followers, preventing the movement from generating a unifying vision for the nation.

As Minister of Labor, Perón cultivated the support of the labor unions, promising to work for them if they swore loyalty to him. He encouraged the development of trade unions in the meat-packing plants, where they had not been allowed before, acted as the moderator in collective bargaining between workers and employers, pressed for improvements in wages and holidays, working conditions, health and pensions--and loudly proclaimed the results when he succeeded. This quickly made him popular. When an earthquake killed more than 10,000 people in the Andean city of San Juan, Perón was put in charge of raising funds for the relief effort, and he did such a good job that he earned widespread praise. At one of the fundraising events Perón organized, he met a radio actress named Eva Duarte (1919-52). It was love at first sight, and Perón's first wife had died in 1938, so Eva became his mistress as soon as the party ended. They would become one of history's most famous partnerships.

Around the same time (January 1944), President Ramirez broke diplomatic relations with the Axis powers. The GOU junta still wanted to be neutral, so it replaced Ramirez with a half-Irish general, Edelmiro Farrell. Perón backed Farrell, and Farrell rewarded his support by making Perón vice president and Secretary of War; he kept his Minister of Labor job, too. However, it was becoming clearer each day that the Allies were going to win the war, and gradually Farrell decided that it would be a good idea to join the winning side. Still, to please the nationalists, he did it in a way that meant Argentina would not have to do any fighting, but the country would qualify for membership in the United Nations, the postwar organization the Allies were setting up. Argentina was the last Latin American country to declare war on the Axis, on March 27, 1945 (less than two months before the European phase of the war ended).

After his promotions, Perón continued to work on all kinds of social legislation, basically passing everything that Yrigoyen couldn't get approved, almost thirty years earlier. By now it was clear to anyone that Perón was a very ambitious man. A group of alarmed officers forced Perón to resign from his jobs, and imprisoned the colonel. Crítica, (then the most widely read newspaper in Argentina), announced the arrest with this headline: Perón is no longer a threat to the country. But they had acted too late. Less than a week after the arrest, on October 17, 1945, hundreds of thousands of workers in Buenos Aires held demonstrations calling for Perón's release, and this scared the junta so much that they set him free and gave his jobs back. The episode proved two things: Perón had a mass movement behind him, and the junta could not deal with a crowd of unarmed civilians. One of the organizers of the demonstrations was Eva Duarte; henceforth she would also be known by the nickname "Evita." A few days later, Juan and Eva were married.

Haiti: Elections and Coups

As with the Dominican Republic and Nicaragua, the only strong and effective institution left behind in Haiti was the police force the Americans set up. The Garde's membership was almost completely black, and it had a US-trained black commander, Colonel Démosthènes Pétrus Calixte, but most of the other officers were mulattoes. Unlike previous Haitian armies, it represented the whole country, not a certain faction or region, and its first loyalty was to a democratically elected government.

Alas, the departing Americans were barely out of sight before President Vincent began to alter the government they had set up, to give himself absolute power. He got a referendum to approve the transfer of control over the economy, from the legislature to himself, but that wasn't enough. In 1935 he produced a new constitution, twisted the arms of the legislature to approve it, and held another referendum to second its approval. This constitution praised Vincent, and gave him control over all three branches of government: he could dissolve the legislature at will, appoint ten of the twenty-one senators, rule by decree when the legislature wasn't in session, and reorganize the judiciary.

Under this system, the only ones who benefitted besides the president were the merchants and corrupt military officers closest to him. One officer who could not be won over was the Garde commander, Calixte, who still believed Haiti came first. Vincent fired and exiled Calixte; later Calixte became a commissioned officer in the Dominican army, a remarkable achievement when you recall what Rafael Trujillo thought of Haitians. Vincent did not stop with Calixte, but purged all officers suspected of disloyalty.

Vincent may have gained supreme power in Haiti, but he had to acknowledge a greater power than his--the United States. After staying quiet for seven years, the Roosevelt administration made it clear in 1941 that it would not let Vincent get elected to a third term as president.(78) Vincent backed down and stepped down, handing over power to Elie Lescot.

Lescot was not an improvement; he had too much in common with Vincent. Both came from the mulatto elite, and were very competent in the government jobs they held before becoming president. But after moving into the top spot, Lescot, like Vincent, repressed his opponents, censored the press, and gathered as much power into his hands as possible. When Haiti declared war on the Axis during World War II, he said the wartime emergency justified his actions, though all Haiti did was supply raw materials to the United States and let the Americans have a Coast Guard base on Haitian soil.

Even more disturbing was Lescot's relationship with the Dominican Republic's tyrant. One of his previous jobs was ambassador to the Dominican Republic, and he became friends with Trujillo during that time; in fact, Trujillo's money was used to buy the legislative votes that allowed Lescot to rise to the presidency. Their secret friendship ended in 1943 for unknown reasons, and after that Trujillo revealed his dealings with Lescot, undermining the Haitian leader's support. But what ended the Lescot presidency was an event now called the Revolution of 1946. In January 1946 Lescot had the editors of a Marxist journal, La Ruche (The Beehive), thrown in jail. Government workers, teachers and shopkeepers launched strikes and protests, and the Garde, which we told you was predominantly black, decided that the mulatto elite had been in charge long enough. The Garde forced Lescot to resign, installed a three-man junta, and instead of trying to elevate one of its officers, it promised free elections to set up another civilian government. Public demonstrations in support of potential candidates forced the junta to actually keep that promise.

A new National Assembly was elected in May 1946, and the Assembly elected a president in August. This time all three candidates were black; the winner, a former school teacher, assembly member, and cabinet minister named Dumarsais Estimé, was the most moderate, and thus considered the safest. He also was a civilian from a humble background, unlike his predecessors who were either from the military of the elite, and genuinely concerned for the people. Estimé's accomplishments included expanding the school system, established rural cooperatives, raised the salaries of civil servants, and opened more government jobs to middle-class and lower-class blacks.

At the same time, though, Estimé offended too many people, especially from the elite. Besides feeling discriminated against, they were mad at Estimé for introducing Haiti's first income tax, encouraging the growth of labor unions, and suggesting that voodoo was just as good as Roman Catholicism (the European-educated elite were Catholics, and wanted nothing to do with voodoo). In addition he alienated foreign corporations by nationalizing the Haitian assets of the Standard Fruit company (modern Dole), and he alienated workers by requiring them to invest between 10 and 15 percent of their salaries in national-defense bonds. When Estimé tried to extend his term in office, the Garde acted, launching a coup and forcing him to resign and go into exile (May 10, 1950). The same junta that had assumed power in 1946 now reinstalled itself.(79)

Because a populist president didn't work out, there was general agreement that the next president would need to be someone who got along with both the army and the elite. Accordingly, the strongest junta member, Paul Eugène Magloire, decided he was the man for the job, resigned from the junta so he could run as a candidate, and got elected. Incidentally, the 1950 election was the first direct election, allowing voters to cast ballots for a presidential candidate, instead of for his party.

The economy did well during the first part of the Magloire presidency, though because the elitists were in charge again, that mainly benefitted businesses and the government. Haiti became a popular resort for US and European tourists, and the US government liked Magloire because he was definitely anti-communist. To Haitians, Magloire was a firm ruler, but not a harsh one. Though he jailed political opponents, and shut down their presses when they protested too much, he allowed labor unions to function, so long as they did not strike.

Unfortunately, Magloire was also corrupt; he controlled the country's sisal, cement, and soap monopolies. When Hurricane Hazel struck Haiti in 1954 and relief funds were stolen, Magloire's popularity fell; Haitians were sure he kept some of the money. Then in May 1956, Magloire made matters worse by disputing the date when his term in office ended. Protesters took to the streets, Magloire declared martial law, and a general strike shut down Port-au-Prince. Magloire gave in first and fled to Jamaica, meaning the army would have to restore order once again.(80)

The next sixteen months (May 1956-September 1957) were stormy, even by Haiti's standards. Of the three provisional presidents during this time, one resigned and the other two were deposed by the army. We believe François Duvalier (see the previous footnote) was actively involved behind the scenes, for when he appeared as a presidential candidate, he had all the advantages, starting with military support. Another was that he had been a doctor before entering politics, and his first job in the government had been rural administrator during a United-State funded campaign against Haitian epidemics, so he was seen as honest and not having a strong ideology. Finally, the only opponent of Duvalier who had a chance of winning, Louis Déjoie, came from the mulatto elite, so Duvalier campaigned as the heir of Estimé. The 1957 election was the first to allow women to vote, and Duvalier won decisively; his party got two-thirds of the seats in the lower house and all the seats in the Senate.

The Duvalier dictatorship was one of the worst in recent history, combining repressive tactics with voodoo and outright crazy behavior. It lasted for 29 years (1957-86), and because all of two of those years occurred after the cut-off date for this chapter, we will pause the narrative here and cover Haiti's dark age in the next chapter. Stay tuned!

Peru: APRA vs. the Army

Two new political parties, claiming to represent the majority of Peru's population, got started in the 1920s, but had to wait until after the coup of 1930 to make their presence felt. The most important was the American Popular Revolutionary Alliance (APRA), founded in 1924 by Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre (1895-1980), while he was exiled to Mexico City. APRA is a nationalist, populist and anti-imperialist movement, usually taking a center-left stand on the issues; it is the oldest active party in Peru today. In 1928 José Carlos Mariátegui founded a more extremist movement, first calling the Socialist Party of Peru, and later the Peruvian Communist Party (PCP).

The period from 1930 to 1968 saw the government alternate between democracy and militarism, as the military and the oligarchy worked together to keep a lid on the APRA and PCP, and the "unruly masses" they represented. The first example came with the 1931 presidential election, when Lieutenant Colonel Luis M. Sánchez Cerro, the leader of the previous year's coup, barely defeated APRA's Haya de la Torre. Claiming electoral fraud, APRA launched a bloody rebellion in Trujillo, Haya de la Torre's home town, in July 1932. Sixty army officers were executed by APRA, and the army retaliated by killing at least 1,000 Apristas (APRA members). Incidentally, some of the latter deaths came from aerial bombardment, the first time bombers were used in South America. Because of this event, the army and APRA had a vendetta for many years, and APRA's participation in elections was restricted in one way or another until 1979.

The Trujillo revolt came at the same time as a border war with Colombia. Peruvian soldiers, not satisfied with the Salomón-Lozano treaty (see footnote #18), occupied the disputed town of Leticia, and clashed with Colombian forces in 1932-33. It took another treaty, this time from the League of Nations, to settle the matter (1934); it ruled that Leticia would stay with Colombia. Meanwhile in Lima, an Aprista assassinated Sánchez Cerro in 1933; Congress quickly elected a former president, Oscar Raimundo Benavides, to finish out Sánchez Cerro's term. With the next election, in 1936, Haya de la Torre was prevented from running, Benavides got a reluctant Congress to nullify the results, and then he had his term extended until 1939.

Fortunately, Peru wasn't affected too badly by the Great Depression. Demand remained good for cotton, lead and zinc during the worst years. Even more important, unlike many other Latin American countries, Peru did not try trade protectionist practices or wage/price controls, so recovery began as early as 1933.

Benavides was succeeded by Manuel Prado y Ugarteche (1939-45), a Lima banker and son of a former president. His administration saw Peru get involved in two wars, World War II and a border war with Ecuador. World War II was the big war, of course, but of the two conflicts it had less of an effect on Peru. Peru rounded up around 2,000 Peruvians and immigrants of Japanese descent and sent them to the United States as part of the US Japanese-American internment program. Aside from that, all Peru did was declare war on the Axis in February 1944.

The Ecuadorean-Peruvian War happened because Ecuador also disliked the Salomón-Lozano treaty. The portion of the Amazon basin held by Ecuador after independence was bordered by two rivers, the Napo in the north and the Marañón in the south; both flowed into the Amazon itself, giving Ecuador indirect access to the Amazon and the Atlantic. But the river mentioned in the treaty, the Putumayo, was a few miles north of the Napo, and Colombia's acceptance of the new frontier gave Peru a claim to all Ecuadorean land east of the Andes. Tensions rose from 1938 onward, and in July 1941 Ecuador invaded the northwest corner of Peru, Zarumilla Province. The Peruvian force was larger and better equipped, and it had no trouble throwing the Ecuadoreans back, after which it staged a counter-invasion of Ecuador. The Ecuadoreans sued for peace, a cease-fire went into effect at the end of July, and a new treaty was signed at Rio de Janeiro on January 29, 1942. The Rio Protocol ceded most of Ecuador's Amazonian territory to Peru, reaffirming previous agreements, and formally defined most of the Ecuadorean-Peruvian border. However, one 49-mile stretch of the border was left undemarcated, and that would lead to two more petty wars (in 1981 and 1995), before the dispute was finally resolved.

A map of the disputed territory between Ecuador and Peru. From Wikimedia Commons.

Domestically, Prado mended the government's relations with APRA, mainly because Haya de la Torre moderated the party platform during World War II. You could say the APRA leader had mellowed, for he was fifty years old at this point. He stopped talking about re-distributing wealth and talked instead about creating new wealth, and he dropped the anti-imperialism rhetoric in favor of calls for democracy, foreign investment, and cooperation among the western hemisphere's nations. In May 1945, shortly before his term ended, Prado legalized the party.

The next president, José Luis Bustamante y Rivero (1945-48), was elected through an alliance with the now-legal APRA. Under them Peruvian policy took a turn to the left; instead of trusting the economy to laissez-faire capitalism, Bustamante favored state intervention to stimulate growth and wealth redistribution; he also increased wages and used controls on prices and exchange rates, when necessary. However these measures were poorly thought out, not well ministered, and done at a bad time; Peruvian exports dropped after World War II ended, because the foreign market did not need as much of them now. The result was more inflation and labor unrest, and the alliance fell apart. APRA controlled Congress and the Cabinet; without their support, the president could not get much done.

In 1947 Aprista militants assassinated Francisco Grana Garland, the director of the conservative newspaper La Prensa. Bustamante responded by dismissing his Aprista cabinet and replacing it with a mostly military one. The new ministers included a hero from the recent war with Ecuador, General Manuel Arturo Odría Amoretti; he became Minister of Government and Police. Soon after that, Odria urged Bustamante to make APRA illegal again; the President refused and Odría resigned. When APRA organized a naval mutiny in 1948, the military, under pressure from the oligarchy, overthrew the government and installed Odría as president.

Just as the eleven-year presidency of Augusto Leguía was called the oncenio, so the eight-year presidency of Manuel Odria (1948-56) is called the ochenio. He came down so hard on APRA that Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre took refuge in the Colombian embassy of Lima, only to find he couldn't leave the country (he ended up staying in the embassy for five years, not going into exile until 1954). At the same time Odria went back to the old-style free market, but otherwise practiced a populist policy to make the poor switch their support from APRA to him. It helped that the economy did better for him than it did for Bustamante; the Korean War brought the price and demand for Peruvian goods up again. Unfortunately it was mainly on the coast where the standard of living rose; highland communities tended to stagnate. Odria used the new revenue to pay for expensive but crowd-pleasing social policies, but otherwise civil rights were severely restricted and corruption ran wild. Consequently many highland peasants moved to the coast to seek jobs, forming a ring of slums (barriadas) around Lima; others went on strike or joined the rebel movements that afflicted Peru in the late twentieth century.

Nobody was fooled into thinking that Odria did not rig the vote, when he ran for re-election and won in 1950. Those who thought he would rule for life got a bigger surprise in 1956, when Odria allowed new elections and said he was not going to run again. The establishment candidate was a former president, Manuel Prado y Ugarteche, but his opponent, Fernando Belaúnde Terry, got more attention. A charismatic reformer, Belaúnde had founded the National Front of Democratic Youth in 1944, and with the way Peruvian elections had been, this was the first time the party had much of a chance of winning. The most dramatic moment came after the National Election Board refused to accept the application Belaúnde filed to become a candidate. Belaúnde's response was to lead a massive protest, now called the manguerazo (hosedown) because the police used water cannon on the demonstrators. To keep the confrontation from turning violent, Belaúnde calmed his supporters and walked across the gap separating the demonstrators from the police, alone and armed with nothing but a Peruvian flag. To the police chief he delivered an ultimatum that his candidacy be accepted. The government backed down and Belaúnde was allowed to run.

Despite winning the war of nerves with the government, Belaúnde did not win the election; he got 36.7% of the vote to Prado's 45.5%. APRA allied itself with its old enemy, the oligarchy, by agreeing to support Prado's campaign in return for legal recognition. Critics called this strange partnership the convivencia (living together), and it showed that the once-liberal APRA was turning conservative. Many disillusioned voters deserted APRA and switched their support to Belaúnde. After the election, Belaúnde went to Cuzco and founded the Popular Action Party (AP), promising to apply the traditional Inca values of community and cooperation to a modern democracy. This move made him the centrist choice, between the pro-oligarchy right-wing and the radicalism of the Communists and other left-wing parties.

Paraguay: The Rise of the Colorados

After an airplane turned José Félix Estigarribia into a red pancake, General Higinio Moríñigo Martínez was given his job. By the world's standards he was brutal and repressive, but by Paraguay's standards, he was rather timid; he didn't go after his opponents as ruthlessly as other Paraguayan dictators did. He also was less eager to go to war; though it had no effect on Paraguay or the outcome of World War II, he waited until 1945 to declare war on Germany and Japan.(81) Elections were scheduled for two months after Moríñigo took charge in 1940, so he suspended the constitution, announced he would be the only commander of the army and the people, and postponed the elections for more than two years. When Moríñigo let them take place, in 1943, he was the only candidate on the ballot.

Moríñigo's main achievement was to install the Colorado Party. Although he claimed no party affiliation, he did so many favors for the Colorados that he left them firmly entrenched in the government. Thus, except for an interruption from 2008 to 2013, they have run the country ever since. In 1946 he formed a cabinet with two parties, the Colorado Party and the Revolutionary Febrerista Party (a minor party); to keep the army friendly while the people were protesting his rule, he gave it 45% of the national budget.

When the Febreristas realized that Moríñigo was interested in helping the Colorados but not them, they resigned and joined the Liberal and Communist Parties in launching a rebellion against his regime. The Paraguayan Civil War lasted for five months (March-August 1947), because the army was also divided; of its eleven divisions, seven supported Moríñigo and four supported the rebels. Moríñigo prevailed, and all parties except for the Colorados were wiped out. In early 1948 he held another election to choose his successor, but two months before Moríñigo's term in office ended, he was deposed by the army. Oh, the ignominy!

The next six years (1948-54) were not as violent, but just as turbulent. Six presidents came and went; two were elected, while the rest were military men; there were also two coups. All six belonged to the Colorado Party, and they came and went so quickly that we won't bother keeping track of their names.

That brings us to Alfredo Stroessner Matiauda, who seized power in a 1954 coup and held the top spot until 1989. If you only knew about one Paraguayan leader before reading this narrative, it would have been Stroessner, because his thirty-five-year reign is the longest in Paraguayan history. By the end of it, 75 percent of Paraguayans had grown up without ever knowing another leader. Like François Duvalier of Haiti, most of Stroessner's reign will come after the end of this chapter, so we will return to him in the next chapter of this work.

Alfredo Stroessner.

Costa Rica: The Unarmed Democracy

The next important Costa Rican leader was Rafael Ángel Calderón Guardia, a doctor and president from 1940 to 1944. He introduced more social reforms, such as paid vacations, unemployment insurance, and national healthcare. A bigger surprise came when instead of backing elite interests, he arranged a powerful alliance between the working class and the Church. However, Calderón also practiced considerable corruption, so he managed to offend both the elite and reformers more honest than himself. In 1944 he was succeeded by Teodoro Picado, who came from the same political party, the National Republican Party (PRN).

One of those reformers who wanted a cleaner government was José María Hipólito Figueres Ferrer, a successful coffee and hemp grower who called himself a "farmer-socialist." In 1944 he founded the Democratic party (later renamed the Social Democratic Party) to oppose the PRN. Then he trained an armed force of 700, which he called the Caribbean Legion, and used it to carry out terrorist attacks in Costa Rica in 1945 and 1946. These were suppose to coincide with a general strike, but the strike didn't happen. Figueres would soon find another use for the Legion, though.

Former President Calderón ran for a second term in the 1948 election, and when it looked like he had lost to another candidate, Otilio Ulate Blanco, Calderón's supporters claimed the results were rigged and invalidated them, but to everyone else it looked like the fraud came from Calderón's camp. Protests over the election results mushroomed into armed conflict, then into a civil war that lasted for forty-four days and killed around 2,000 people. With some aid from Cuba and Guatemala, Figueres defeated Communist-led guerrillas and the Costa Rican Army, to come out on top.After the civil war Figueres became president, leading a provisional junta known as the Junta Fundadora (Founding Council), which held power for eighteen months. While the junta lasted, he was exceptionally busy. In a 1981 interview, he explained: "In a short time, we decreed 834 reforms that completely changed the physiognomy of the country and brought a deeper and more human revolution than that of Cuba." The purpose of those reforms was to transform the country into a welfare state.(82) He put taxes on the wealthy, nationalized the banks, and wrote a constitution that granted full citizenship and voting rights to women, blacks, Native Americans and Chinese.

Most amazing of all, Figueres abolished the military. He had plenty of examples in Latin America of the military threatening and ending democracy, and would nip that danger in the bud. As he put it: "The future of mankind cannot include armed forces. Police, yes, because people are imperfect." Since 1949, Costa Rica has had no army and has maintained a 7,500-member national police force for a population that is now four and a half million. Of course, other nations have not willingly laid down their arms, because this imperfect world is governed by the aggressive use of force; all too many people and governments believe that "might makes right." So far, doing without any armed forces has worked for Costa Rica because it has powerful friends like the United States.(83) When Figueres was done, he handed over power to Otilio Ulate Blanco, giving him the term in office he had been denied, one year earlier. In 1953 Figueres started a new party, the National Liberation Party (PLN), and was returned to the presidency in that year's elections. His second term lasted until 1958.

Costa Rica's no-military policy went through its toughest test in a border war with Nicaragua. Ever since Costa Rica did away with its army, Figueres had used the Caribbean Legion in plots to overthrow right-wing dictatorships in the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, and Nicaragua. It was a dangerous game, because any of those tyrants could retaliate against a defenseless Costa Rica, if it was caught in the plots. In 1954 he supported some exiled opponents of the Nicaraguan dictator, Anastasio Somoza García, as they snuck back into Nicaragua. Somoza found out, and invaded Costa Rica in January 1955, supposedly to reinstate former president Calderón. Figueres called on the Organization of American States to help; the OAS ordered a cease-fire and sent a delegation to investigate the crisis.

Somoza realized that he needed help, too, and the ally he could count on was the US Central Intelligence Agency. The CIA owed him a favor, because in 1954 he had allowed them to use Las Mercedes Airport, outside Managua, for air strikes while intervening in Guatemala. Now he wanted to use the P-47 Thunderbolt fighters parked there, in his feud with Figueres, so three days after the OAS action, a P-47 bombed and strafed targets in Costa Rica.

Because Costa Rica had no defense against World War II aircraft, Figueres appealed to the OAS again, and the OAS immediately authorized the United States to sell four P-51 Mustang fighters to Costa Rica for the bargain-basement price of one dollar each. At that point, some US congressmen were pleading with the US State Department to rescue the region's "lone democrat," and the United States needed to clean up its image after Guatemala, so the planes were sold. Somoza called off the invasion when he heard the news, but before withdrawing he got a commitment from Figueres to stop dealing with the exiles. The final score? It was a fight between two US client states, one backed by the CIA and the other backed by the State Department, with the State Department scoring the winning point.

Figueres hated communism; at the end of his second term he sent a planeload of arms to Cuba, to aid Fidel Castro in his war against Batista, but turned against Castro's regime after it became fully Communist. In March 1959, Figueres was invited to Havana, and during a public speech, he warned Castro about the growing Communist influence he had seen in Cuba; immediately the microphone was taken from him. Because of his dislike of communism, Figueres gave the US armed forces his full cooperation. The United States established the School of the Americas in the Panama Canal Zone to train Latin American officers in Anti-Communist techniques, and from 1950 to 1965, more Costa Rican "police" graduated from the School than did officers of any other nation in the region, except Nicaragua.

But Figueres also hated dictators of any ideology, whether they were left-wing or right-wing. In that sense, he was more consistent than the United States, which at this stage tended to only oppose left-wing dictators, while giving right-wing dictators a pass. He explained it thusly in a 1951 interview: "Your hands are not clean to fight communism when you don't fight dictatorships. It seems that the United States is not interested in honest government down here, as long as a government is not communist and pays lip service to democracy."(84) For that reason, Figueres respected and admired the United States, but did not always toe the American line. When the United States held an inter-American conference in Venezuela in 1954, Figueres refused to attend, because Venezuela's dictator, Marcos Pérez Jiménez, was the host. He also supported the Sandinista movement when it overthrew the Somoza dictatorship (1979), but refused to back the Contras when Nicaragua went the way of Cuba. Overall, the success of Figueres' vision for Costa Rica shows in how his system is still running today, more than sixty years after he set it up.(85)

"There's No Place Like Uruguay"

The Amézaga administration saw industrialization and significant changes. Overall the mood was upbeat, and the most popular slogan of the time was "Como el Uruguay no hay" (There's no place like Uruguay). In 1943 the government established wage councils to set salaries (membership in the wage councils came from the government, workers, and employers), and also a family assistance program. In 1945 the General Assembly passed legislation requiring paid leave for all workers. In addition, the government worked to improve the lives of rural workers, who had always been poor, and guarantee civil rights for women.

If the above paragraph sounds likes a rerun of the years when José Batlle y Ordóñez was in charge, it definitely was after 1946, when the Batlle family returned to power. The next president, Tomás Berreta, died after only six months in office, and was succeeded by his vice president, Luis Batlle Berres (1947-51), a nephew of Batlle y Ordóñez. Also prominent were two of his cousins--Lorenzo and César, Batlle y Ordóñez's sons--who became opponents of his and formed a new conservative faction within the Colorado Party. Batlle Berres himself rejected the communist and populist approaches of other Latin American countries, especially that of Juan Perón in Argentina. His own philosophy, a multiclass movement that promoted compromise and conciliation, was against the government working too closely with corporations, except to correct the "unfair differences" created by society and the economy; this came to be known as "Neo-Batllism."

The winner of the 1950 elections was another Batllist, Andrés Martínez Trueba (1951-55), who promised to try Batlle y Ordóñez's proposal for a council of executives, the colegiado. He was supported by Herrera, who saw this as a way to recover the power the Blancos lost in 1942, and by conservative Colorados who did not want Batlle Berres to run again. As promised, he had a new constitution (the fifth so far for Uruguay, in case you're keeping track) written, which was approved by plebiscite in 1951 and went into effect in 1952. Instead of a president, the country was now led by a National Council of Government. Six of the council's members would come from the ruling party, and the other three would come from the party that came in second place in the elections. Unfortunately it did not work as well in practice as it did in Switzerland. The nine members of the council could not make quick decisions, and were frequently locked in disagreement, so after another plebiscite was held on the matter in 1966, the council was abolished.

Quick decision-making mattered, because Uruguay suffered an economic slump in the 1950s. During the Korean War, the United States bought large amounts of wool for cold weather uniforms; after the war ended in 1953, worldwide demand not only dropped for wool, but also for other Uruguayan agricultural products. From 1955 onward, industry also stagnated, inflation set in, and labor unrest and unemployment increased. This led to an upset in the elections of 1958. All three Blanco factions agreed to put their votes together, meaning that for the first time in decades, the National Party voted as one party. Herrera also got the support of a radical labor union that was acting as a political movement, so for the first time since 1865, the Blancos gained control over the executive branch of the government.

The Bolivian National Revolution

The Bolivian Nationalist Revolutionary Movement (MNR) had a comprehensive program when it came to power in 1952, and the ultimate goal of that program was to raise the status of three groups that had not done very well since independence: women, workers, and most of all the Indians, who make up about 65 percent of Bolivia's population. Paz Estenssoro and the radicals in the MNR were in a hurry to act because they felt the need to keep their promises right away; if any part of their program was postponed, somebody would probably find an excuse to not do it at all. Accordingly, one of the first things they did was pass universal suffrage; all literacy and property requirements were eliminated. As expected, this caused a tremendous increase in the voter rolls; whereas 200,000 were eligible to vote in the 1951 elections, the next time elections were held, in 1956, there were nearly 1 million voters. To forestall a coup from the army, the nemesis of all previous civilian governments, the government dismissed officers associated with past Conservative Party regimes, drastically cut the size and budget of the armed forces, closed the Military Academy, and required that officers take an oath to the MNR.

Next on the agenda were the mines. The three largest tin companies, which together controlled two-thirds of Bolivia's mining industry, were nationalized. Instead of letting them be run by absentee owners, which had been the case until now, the Mining Corporation of Bolivia, partially run by the state and partially run by representatives of the workers, was set up to manage them.

Step three was land reform. In January 1953 the government established the Agrarian Reform Commission, and decreed the Agrarian Reform Law in August. This law abolished forced labor and established a program of expropriation and distribution of the least productive estates, giving them to the Indian peasants; those landlords who lost land would be compensated with twenty-five-year government bonds. Finally, a Ministry of Peasant Affairs was created to manage the distribution of land, give arms to the peasant militias, and organize the peasants into syndicates. These actions would make the peasants a powerful political force under all subsequent governments.

However, in one way the land reform was a step backward. To the Indians, it was a way to preserve or revive the way of life they knew before the Spanish conquest and modern capitalism, and keeping tradition is a conservative activity, not a revolutionary one. At the same time there is nothing conservative about granting universal suffrage and giving privileges and arms to miners, so those benefitting from the revolution would not speak with a united voice after 1953, leading to divisions between the peasants, workers and middle class factions of the MNR.

The most amazing thing about the Bolivian revolution was the response of the United States to it; indeed, all the activities above could only be carried out successfully because the US gave aid from 1953 onward. We have seen that in other times and places, the US preferred the status quo, so it was inclined to back right-wing governments--which were more likely to toe the American line and less likely to give surprises--rather than left-wing governments. But in Bolivia's case, the US diplomats stationed in La Paz successfully persuaded Washington that the MNR's revolution was likely to fail if it did not have lots of money, and if it failed, the result would be chaos and communism. So Uncle Sam gave the funds that were needed, with an eagerness that startled both Americans and Bolivians. This was the first time the US cooperated with a progressive Latin American government, even while some of its members were denouncing "Yankee imperialism" and engaged in behavior (e.g., the nationalization of mines) that Americans generally frowned upon. Besides peace of mind over the idea that Bolivia would not go communist, the Americans also got the Bolivian government to write a new petroleum code, allowing an American company, Gulf Oil, to invest in Bolivian oil (the first foreign investments in twenty years). Finally, it helped a lot that the Bolivians modeled their revolution after the one in Mexico, not that of the USSR or any other communist nation; e.g., they brought in Mexican consultants to advise them on how to implement the land reform. Compare this with the US response to land reform in Guatemala, later in this chapter.

Although the big three steps of 1952-53 were never reversed, the MNR ran out of steam after that, and started to break up. The main problem was a bad economy. Nationalization of the mines caused them to run at a loss, because of a shortage of technical expertise; what's more, the equipment was obsolete and the only available tin ore was low-grade. Meanwhile, anarchy in the countryside and the lack of transportation meant lower agricultural production. And then there was hyperinflation. In 1952 it took 60 Bolivian pesos to equal one US dollar; in 1956 the exchange rate was 12,000 pesos to the dollar. Because this hurt city-dwellers the most, they began to support opponents of the MNR.

Paz Estenssoro was succeeded by his vice president, Hernán Siles Zuazo, who served as president twice (1956-60 and 1982-85). US aid peaked during his first term; in 1957, the Americans paid for more than 30 percent of the Bolivian government's budget. However, accepting the aid also meant accepting guidance from the US. Washington and the International Monetary Fund brought down inflation by recommending politically dangerous measures, such as the freezing of wages and the ending of government subsidies for the miners' stores; this led to unrest in both the mines and the countryside. To control discontent, Siles Zuazo enlarged the military, and gave it new equipment and training; again, the United States provided the money to do it. Thus, when Siles Zuazo's term ended in 1960, the MNR may have looked more reactionary than revolutionary.

This is the end of Part IV. Click here to go to Part V.

FOOTNOTES

69. Gunther, John, Inside Latin America, London, Hamish Hamilton, 1942, pp. 281, 291.