| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A General History of the Middle East

Chapter 3: THE EARLY IRON AGE, PART II

930 to 627 B.C.

This chapter is divided into two parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| The Phoenicians | |

| Israel vs. Judah vs. Aram (Syria) | |

| The Hittites Fade Out | |

| Troy, the City With Nine Lives | |

| The Sea Peoples | |

| The House of Omri | |

| Assyria: The Calah Period |

Part II

| Israel's Indian Summer | |

| Urartu | |

| Phrygia | |

| The Mannaeans | |

| The New Assyrian Empire | |

| The Rise of Lydia | |

| Josiah the Righteous | |

| Assyria Triumphant | |

| Go to Page Navigator |

Israel's Indian Summer

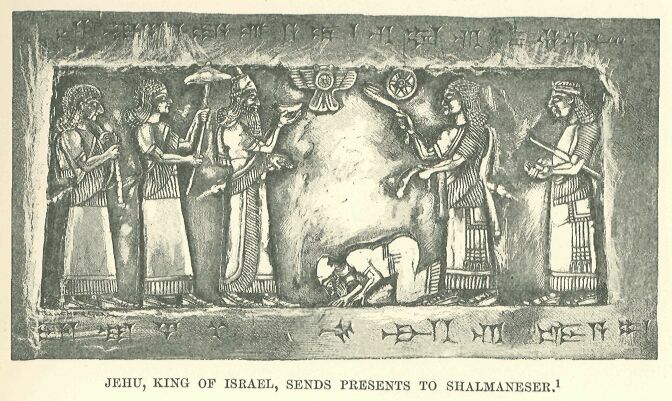

A furious charioteer named Jehu wiped out the dynasty of Omri in 841 B.C. He chased Jehoram, the king of Israel, shot him dead with an arrow, and because Ahaziah, the current king of Judah, happened to be there, Jehu mortally wounded him, too. A wholesale slaughter followed, with Jehu ordering the execution of seventy sons of Ahab and forty-two relatives of Ahaziah. Then Jehu vigorously persecuted Baal-worshipers in Israel, but failed to stamp out idolatry completely; because of his efforts, though, Elisha promised that Jehu's family would hold the throne for four generations. Shortly after that Shalmaneser III attacked Aram, and Jehu chose to pay tribute to the Assyrians rather than fight them. This event is recorded on a stone known as the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser; with the exception of a statue in Egypt identified as Joseph's, this may be the only representation we have of a Biblical character that was made during his lifetime. The king of Aram, Hazael, never forgave Israel for that, and attacked more aggressively than his predecessors had. The loss of all Israelite territory east of the Jordan marked an ominous end to Jehu's career. Under his son Jehoahaz, Israel lost Galilee and the coastal plain to Aram; the kingdom was reduced to a county-sized state in the highlands around Samaria. Hazael advanced far enough south on the coast to take the Philistine city of Gath, and even made a successful raid on Judah.(16)

Archaeologists have noted that during the early iron age, pottery made in styles common on the east bank of the Jordan began turning up on the west bank as well. To them this means a westward migration across the Jordan River took place; those making the move continued to make their pots in the same fashion afterwards. Moreover, conventional chronologies put the Exodus near the end of the bronze age, so this is also seen as evidence of the Israelites moving into Canaan under Joshua. However, the chronology used in this work has the Exodus in the middle of the bronze age, so the early iron age migration becomes an event that happened centuries later. For us, this is evidence of depopulation in the areas conquered by the Aramaeans, as members of the east bank tribes (Reuben, Gad, and Manasseh) became refugees, fleeing Hazael's chariots and relocating to Israel's core territory.

While Jehu was conducting purges in Israel, a counterrevolution took place in Judah. Queen Athaliah seized the throne and exterminated the entire dynasty of David except for an infant named Joash, who was hidden and raised in the Temple by his aunt and the high priest, Jehoiadah. This was a really low point for Judah, now ruled by the daughter of Ahab & Jezebel and the granddaughter of a Sidonian priest-king of Baal. When Joash reached the age of six, Jehoiadah revealed him to the public and crowned him; Athaliah was killed when she tried to interfere. Joash's early years as king went well; with Jehoiadah as his advisor, they gave the Temple some much-needed repair work. Jehoiadah lived to the ripe old age of 130, and was buried among the kings of Judah; with this positive influence gone, Joash was rapidly corrupted into idolatry, and eventually assassinated by two of his servants.

Joash's successor was an overconfident king named Amaziah who reconquered Edom and picked a fight with Jehoash (see below); Jehoash came out the winner. For the only time in Judah's history Jerusalem surrendered to an army from the northern kingdom. Jehoash removed the treasures of the Temple and 600 feet of Jerusalem's wall; Amaziah spent the rest of his life as a hostage of Israel. Amaziah's righteous son, Uzziah (791-740 B.C.), gave Judah a long period of prosperity to match what Israel was now enjoying.

In the north, Israel was rescued from the Aramaeans by a mysterious "savior," who is mentioned, but not identified, in 2 Kings 13:5. Most likely it was Assyria's Adad-nirari III, who broke Aramaean strength in a devastating raid on Damascus in 806 B.C. Another possibility is Shoshenk I of Egypt's XXII dynasty; on a wall at the great temple of Karnak, this pharaoh recorded a campaign in Israel near the end of his reign. Finally, there is the distant possibility that Sammuramat (see the next section), the mother of Adad-Nirari III, was the savior, but to accept her as a candidate you also have to believe the legends about her leading armies, and assume that the author of 2 Kings didn't mention her name because he was a male chauvinist.

Around 798 B.C., Jehoash became king of Israel, and Elisha made his last prophecy, predicting that Jehoash would defeat, but not destroy, his Syrian foe. Sure enough, Hazael died and was succeeded by his son, Ben-Hadad III, and Jehoash recovered all of Israel's lost territory. His successor, Jeroboam II (793-753 B.C.), conquered Ammon, Moab, and the Syrian cities of Damascus and Hamath, making Samaria the capital of the wealthiest, most powerful nation in the Levant since Solomon's day. We sometimes call these decades of prosperity in the early 8th century B.C. "the Indian Summer of Israel," because Israel's downfall came swiftly afterwards.

If you're not a Bible scholar, you probably haven't heard of Jeroboam II. The Bible only has seven verses describing this important king (2 Kings 14:23-29), and they are a laconic list of his achievements. This is because the Bible is mainly interested in spiritual matters; when it covers history, it does so to give examples of people acting right or wrong. Thus, the author of 2 Kings felt he said enough by telling us that Jeroboam "did evil in the sight of the Lord," and that he practiced the sins of the first king named Jeroboam, but God allowed Jeroboam II to be successful because He had promised Israel would not be destroyed in this generation. For us, the important point to remember is that the economic and political gains achieved by Jeroboam II and Uzziah were not matched with spiritual progress. The prophets of the day (Hosea and Amos in Israel, Isaiah and Joel in Judah) preached against the hypocrisy they saw. The leadership of Israel and Judah carefully observed sacrifices and holidays, but oppression, bloodshed and greed were commonplace; the rich got richer while the poor got poorer. The prophets started declaring that God would judge and scatter His chosen people because they had forgotten their creator and protector.

Jeroboam II was succeeded by his son Zechariah, and true to the prophecy of Elisha, the dynasty of Jehu ended there; he was murdered only six months after taking the throne of Israel. The killer, Shallum, was turn slain a month later by a general named Menahem. Menahem ruled from Samaria next, but another general, Pekah, refused to recognize Menahem's coup, and set up a rival kingdom east of the Jordan River. Then after Menahem's death, Pekah killed Menahem's son and reunited the kingdom under himself. Meanwhile in Judah, the succession passed peacefully from Uzziah to Jotham to Ahaz, but all was not well there, either. In 736 B.C., Pekah of Israel and Rezin, the last Aramaean king of Damascus, joined forces to attack Judah, and Judah's Ahaz got the Assyrians to rescue him, by sending treasures from the Temple and his palace. By this time Tiglath-Pileser III was king of Assyria, and inviting him to attack your enemy was like chasing a wolf from the front door of your house by letting a tiger in through the back door! We will come back later to Tiglath-Pileser and the Assyrian conquest of the Levant, but now we should take a look at what the tribes and nations outside the Fertile Crescent were doing in the late ninth-early eighth centuries B.C.

Urartu

From 824 to 745 B.C. Assyria was ruled by five kings and one queen. The latter was one Sammuramat, wife of Shamshi-Adad V, who ruled from 811 until her son Adad-nirari III came of age in 806 B.C. She is scarcely mentioned in Assyrian records, which definitely wanted to give all the glory to men, but in later Babylonian accounts she became a legendary figure named Semiramis, "the most beautiful, most cruel, most powerful, and most lustful of Oriental queens." Apparently the priests of Babylon wanted to erase the accomplishments of the Assyrian kings, so they credited them to somebody else; the imagination of gullible travelers did the rest. The original view of Semiramis as an Ishtar-like character comes to us from Herodotus; later historians like Strabo and Diodorus Siculus further embroidered the story, as did modern operas and plays by Voltaire, Cimarosa and Rossini. They called Semiramis the builder of Babylon and the conqueror of Egypt and India, and her name came to symbolize the vanished glory of Mesopotamia. By an ironic trick of fate the virile Assyrian empire builders were forgotten until their cities were rediscovered in the nineteenth century, while their legacy came to us in the form of legends about a woman.(17)

The most capable Assyrian monarch during this period was Adad-nirari III (811-783). As seen earlier in this chapter, he succeeded where Shalmaneser III failed by defeating Syria; he also took tribute from the Phoenicians, Philistines, Edomites, Israelites, Medes, Persians, and Anatolians. Nevertheless, Assyrian power was limited, having suffered a severe setback in the civil war of 828-821. Campaigns failed more often than they succeeded, Assyria's borders shrank back toward the core territory, and there were epidemics and an ominous eclipse of the sun. It was sometime during this period that the prophet Jonah visited Nineveh. While Assyria was in eclipse, the rest of the Middle East enjoyed a time of relative peace.

We mentioned the prosperity of Israel and Judah during this time in the previous section. Another nation that did well was Urartu, a new kingdom in Armenia. In Chapter 2 we saw a collection of city-states and tribes, called the Nairi by the Assyrians, in this region. Then in the time of Shalmaneser III, a king named Arame (858-844) united the Nairi into one state. He built a fortified capital at Arzashkun (location unknown), but Shamaneser captured it, and we don't hear from Urartu again until after Shalmaneser's reign ends.

The new state appears to have included both proto-Armenians and non-Armenian peoples, because the official language was related to Hurrian. Thus, the kingdom was not ruled by Armenians, but because of its location, today's Armenians claim it as the first state of theirs to appear in historical records. Even the name we normally use for it is foreign; the inhabitants of the kingdom called it Biainili, while the name "Urartu" comes from Assyrian clay tablets. The Urartians adopted the use of cuneiform from the Assyrians, and though we can read their language, so far we have only found a few tablets from them, so Urartu's history, like that of the Elamites, comes with gaps in it. We may have the missing details at a later date, though; some 300 Urartian sites have been identified in Armenia, Iran, Iraq and Turkey, but less than half of them have been excavated, due to the chronic warfare and instability of the Middle East.

The next king, Sardur I (844-828), was not the son of Arame, but of an otherwise unknown individual named Lutipri. He did better, building a new, more permanent capital at Tushpa (modern Van). Under him the kingdom expanded to dominate everything between the three great lakes of the Transcaucasus region: Lake Van, Lake Sevan and Lake Urmia. It stretched south to the northern border of present-day Iraq, and north to the Kura River in Georgia. Within its borders were the upper reaches of the Tigris, Euphrates and Araxes Rivers, not to mention Mt. Ararat, which now carries a modern version of Urartu's name. His successor, Ishpuini the Establisher (828-810), conquered Musasir, a neighboring city-state; Chaldi, the god of Musasir, became the chief god of Urartu as a result. Ishpuini also appointed his son Sardur II as the kingdom's viceroy, but two other relatives got to wear the crown first: Menua (810-785), a younger brother of Sardur II, and Menua's son, Argishti I (785-763).

From a military standpoint, Argishti I was Urartu's most successful king. He added more territories along the Araxes River and Lake Sevan, pushed the northern frontier almost all the way to Colchis, the city-state of the Golden Fleece, and defeated invasions from his Assyrian counterpart, Shalmaneser IV. One Urartian campaign even captured Babylon. From about 780 to 747, the kings of Babylon are described as "Chaldean," but it is likely they were Urartian, with the first one being a puppet governor installed by Argishti; the association of Chaldea with the Persian Gulf came a few decades later (see footnote #21). Also worthy of note is that Argishti founded Erebuni in 782 B.C., which later became modern Armenia's capital, Yerevan. Beyond the kingdom's borders came tribute from the Neo-Hittites, the Cimmerian tribes in the Caucasus, and the Mannaeans (Mannai), an advanced tribe in Iran. Urartu prospered because of rich farmlands along the Araxes River, cow pastures near Mt. Ararat, and most of all, from copper and iron mines within its territory. In fact, the real source of Urartu's wealth and strength was in its skill at metal working; the finest artifacts we have from that civilization are all made of metal.

Urartu's power peaked when Sardur II finally got his chance to rule (763-735); he persuaded the Aramaeans of Syria to transfer their allegiance to him. This made the kingdom a northern rival to Assyria, because it now threatened to surround the Assyrians on three sides (east and west as well as north). To prevent that from happening, Assyria would have to conquer and firmly hold Syria and Iran. The time of quick and easy raids was over; Assyria had no choice but to become an empire or perish.

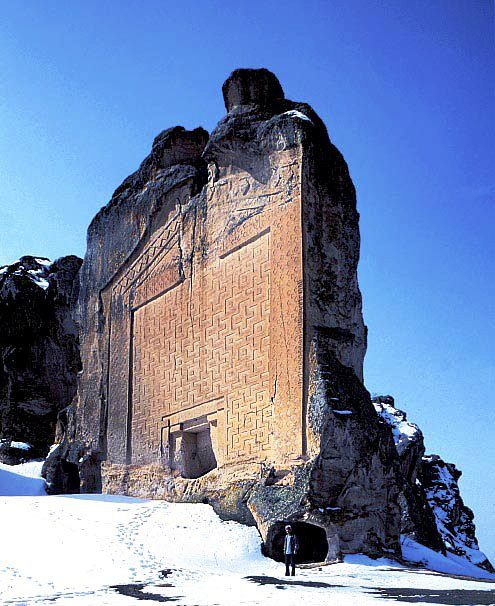

Phrygia

In the Anatolian interior, a little-known people called the Phrygians set up a kingdom of their own; the founding date is uncertain, except that it happened before 800 B.C. Their exact origins are also unclear, and a source of controversy; all we know for sure is that they were an Indo-European tribe. Because the Phrygians lived just east of the Ionian city-states, the Greeks mentioned them often; they reported that the Phrygians migrated out of the Balkans, and their first leader was named Mygdon. They arrived a generation before the Trojan War (900 B.C., give or take a few years), and marched with a youthful King Priam to the Sakarya River, where they fought the Amazons.(18) Then when the Trojan War itself broke out, they fought on the side of the Trojans. For most modern historians, this information is enough to give the Phrygians a European origin. On the other hand, the Assyrians called them Mushki, which suggests they came from the east; unfortunately there is no way of telling whether these were the same people as the Mushki that Tiglath-Pileser I fought (see Chapter 2). Excavation of Phrygian sites have revealed that they wrote with an alphabetic script, borrowed from the archaic Greek alphabet, but so far the Phrygian language has not been translated.

Like many other pagans, the Phrygians believed that the two most important gods were an earth goddess and a sky god. In this case, "Mother Earth" was named Cybele, and "Father Sky" was called Sabazius. Later on, for reasons unclear to us, the Greeks would see Cybele as an Asian version of their chaste huntress, Artemis, while Sabazius would be seen as either Zeus or Dionysus, depending on who you're reading.

According to Greek myth, the Phrygian Kingdom was founded by a declaration from the temple of Sabazius. Once upon a time the Phrygians had no king, and asked the temple's oracle who should be king over them. The oracle answered that the honor should go to the next man who rides up to the temple in an ox-cart. Meanwhile, an eagle landed on the ox-cart of Gordias (also spelled Gordius), a poor farmer from Macedonia. Like the Etruscan prophetess Tanaquil, Gordias saw this as a sign that the eagle was paying homage to a future king, because the eagle is a royal symbol. As he drove to the oracle of Sabazius, the eagle stayed on the cart, which to him was another sign. At the gate of the city surrounding the temple and oracle, he met a seeress, who told him to offer sacrifices. Here was the exchange between them:

Seeress: "Let me come with you, peasant, to make sure that you select the right victims."

Gordias: "By all means. You appear to be a wise and considerate young woman. Are you prepared to marry me?"

Seeress: "As soon as the sacrifices have been offered."(19)

Then the seeress joined Gordias in the ox-cart and they rode up to the temple, where as predicted, Gordias was acclaimed king. To thank Sabazius for this sudden promotion, he donated his ox-cart, and tied it down with an elaborate knot of rope, the famous Gordian knot. The kingdom's capital would be renamed after him, too--Gordium.

Today Gordium is Yassihöyük, a flat mound fifty-five miles southwest of modern Ankara. Like Troy, Yassihöyük also holds artifacts from other eras, ranging from the early bronze age to the Galatian and Roman periods (see Chapters 6 & 7). The archaeologists have given most of their attention to the Phrygian level, as you might expect, and the main thing they learned was that the city was destroyed by fire. Too much of it burned down for the blaze to be considered an accident, which agrees with the Greek claim that it was an act of arson on the part of nomads from Russia, the Cimmerians.

Whereas the Hittites and Urartians prospered because of iron, the Phrygians prospered because the rivers in their kingdom had deposits of gold and silver. To explain where the gold came from, the Greeks told the myth of King Midas, Phrygia's most important ruler, and the Golden Touch. For those not familiar with the story, one day a weary stranger came to the palace of Midas; the king took him in and after the stranger freshened up, he provided the court with entertainment for ten days. Then the god Dionysus appeared, and told Midas that the stranger was Silenus, his tutor. In payment for Midas' act of kindness, Dionysus would grant his fondest wish. Midas said, "I wish that everything I touch will turn to gold!" When the first things he touched became gold, he thought for sure he would be the richest man in the world, until he learned that the new gift was a curse, rather than a blessing. At mealtime, he found he could not eat because the food turned into inedible gold in his mouth, and when he touched his daughter, she became a golden statue. Midas pleaded with Dionysus to take the Golden Touch away, and Dionysus told him to bathe in the Pactolus River, saying, "You shall be cleansed of the Golden Touch, and perhaps of your greed, too." Midas jumped into the river, and his power passed to the water, turning the sand on the bottom of the river into golden sand. Since the Pactolus runs by Sardis, the future capital of Lydia, this guaranteed a fortune for King Croesus later on (see Chapter 4).

The Phrygians also gave us a fashion that is still in use, but you probably don't think of the Phrygians when you see it--the Phrygian cap (see the next picture). This is a conical, felt hat, usually red, with a jaunty curve on top. In Roman times the Phrygian cap was associated with Asians, so followers of the Iranian god Mithras (see Chapter 8) made statues and paintings of him wearing one. Ex-slaves also wore it as a sign that they had been freed, making it a symbol of freedom. For that reason, the Phrygian cap has been very popular in France, from the French Revolution to this day. Finally, the Smurfs wear a white version of the cap, except for Papa Smurf, who stayed with the red.

The most interesting Phrygian discovery to date was in the largest of more than eighty burial mounds near Yassihöyük. This was penetrated in two seasons of digging (1951 and 1957) by a team from the University of Pennsylvania, led by archaeologist Rodney S. Young. In the mound (which was 170 feet high and 980 feet wide) they found an undisturbed burial chamber, containing an old man's skeleton in an open boat-shaped coffin, and the oldest wooden furniture ever found outside of Egypt. Also present were cauldrons, plates, cups and ladles, from a funeral banquet held just before the tomb was sealed up. These items contained enough residue from the feast to determine the food and drinks served, and that there was enough to feed a hundred guests. Since the excavation, this site has been called the "tomb of Midas," but it now appears to have belonged to an earlier king, most likely Gordias, because no gold, silver or jewelry was found. You wouldn't expect a king famous for his greed to be buried without that!

The Greeks gave us the names of only three Phrygian kings--Mygdon, Gordias and Midas--but because the Phrygian kingdom lasted for about two centuries, there must have been more. For example, there had to have been at least three kings named Midas. The first Midas lived just before the fall of the Hittite Empire, when Arnuwandas III, the second-to-last Hittite king, reported trouble on the northeastern frontier with a local ruler named Mitash of Pakhuwa. This would put his tribe in the land that would someday be called Pontus, but historians have no trouble assuming that Mitash is another way to spell Midas, and that the Phrygians lived somewhere else before settling in the heart of the former Hittite Empire. The second Midas ruled in the first half of the eighth century (ca. 785-765 B.C.); this is the best candidate for the Midas of the Golden Touch story. Midas II was followed by Gordias, and the last king would have been Midas III (ca. 725-696 B.C.), who ruled when Gordium was destroyed.

Under Gordias, the Phrygian kingdom expanded far enough east to encroach upon Urartu. However, this brought Phrygia into contact--and conflict--with the Assyrians, who had now gotten their act together, after an eighty-year period when nothing seemed to go right. The new Assyrian king, Tiglath-Pileser III, transformed the Assyrian state from a "first among equals" kingdom into a fullscale empire. He also vowed to "smash like pots" any nation that opposed him, especially Urartu. Thus, the Phrygians prepared for an inevitable confrontation by building strong walls around their cities, along with underground passages and wells to provide water in the event of a siege. These defenses stood firm against the Assyrians, but failed to stop Assyria's barbarian allies, as we will see in a later section.

The Mannaeans

We haven't heard from the Elamites since Chapter 2 of this work, and hopefully someday records will turn up, to tell us what they were doing for the two centuries between 970 and 770 B.C. About the only one we have comes from Babylon, which states that in 813 B.C., the Babylonian king Marduk-balassu-iqbi fought the Assyrian king Shamshi-Adad V, and Elamite troops helped the Babylonians. Although the Elamites still had the southern half of present-day Iran to themselves, we now hear reports of several new neighbors in the north, Indo-Iranian tribes like the Medes, Parthians, Sagartians, Margians, Bactrians, Sogdians, and Persians. Soon they would expand southward into the Elamite domain as well.

Between 900 and 700 B.C., the most important group of newcomers were the Mannaeans. They appear in Assyrian records as the Mannai, and in the Bible as Minni (Jeremiah 51:27); they founded a kingdom called Mannea, in what is now the Iranian part of Kurdistan. We are not sure how the Mannaeans are related to the other Indo-Iranians; the current theory is that they were really from several tribes and united for a common cause, much like how today's Swiss are a combination of ethnic Germans, French, Italians and Romansch. The Mannaean capital, Izirtu, has not yet been located.

Most of the artifacts we have from the Mannaeans were discovered at Hasanlu, a community on the south shore of Lake Urmia. Here a team of archaeologists from the University of Pennsylvania, led by Robert Dyson, Jr., excavated from 1956 to 1977. They hit paydirt in 1958 when they discovered the "golden vase," a fancy golden cup the size and shape of a small bucket. Of course they rejoiced over this, but soon they were sobered up by the discovery of 246 skeletons of men, women and children. Many were killed by falling walls or roofs, and the rest bore grievous wounds, showing that everyone died violently. The conclusion reached was that Hasanlu was destroyed by Urartu around 800 B.C.; moreover, at least three of the victims had died fighting over the golden vase.

Mannea was drawn into the conflicts of the Middle East because both Urartu and Assyria wanted the kingdom's territory. The Urartians got the better of the first clashes, as we saw at Hasanlu, and managed to build several forts within Mannea. Then after 750 B.C., success shifted to the Mannaeans, and they expanded outward. The kingdom peaked during the reign of Iranzu (725-720 B.C.), but not for long. This was because Iranzu's success challenged the Assyrians, who were now strong enough to take on both Urartu and Mannea at the same time. For more about that, read on!

The New Assyrian Empire

Tiglath-Pileser III was the first Assyrian king since Shalmaneser III to realize that the political situation had changed, and during his reign (745-727 B.C.) Assyria made a more than complete recovery. His administrative reforms were extensive, to start with. To limit the power of the old governors, he multiplied Assyrian provinces and made them smaller. Wherever possible, defeated princes, instead of merely being required to pay and promise, were replaced by loyal governors and tax collectors. Now the Assyrians made permanent conquests of their enemies, instead of simply raiding them and calling it a victory. They built new roads, and a relay system of runners was set up to carry messages to any part of the empire within a week or two. In the courts of nations not directly under Assyrian rule, representatives were sent to keep a watchful eye on everything that interested Assyria, including an uninterrupted flow of tribute.

Tiglath-Pileser also reorganized the Assyrian army to make it the largest, most formidable fighting machine the world had seen up to that time. Previously they had called up a new army every spring; because it was made up of just Assyrians, it never exceeded 50,000 men, and everybody in it went home at harvest time. Now in its place came a permanent standing army whose core was still Assyrian but included foreign mercenaries and conscripts from vassal states and annexed provinces. The new army at times had a total of 200,000 men, but its ill-assorted and often untrustworthy foreign elements were inferior in endurance and courage to the tough Semitic peasants from northern Iraq. For the mountain campaigns, Tiglath-Pileser enlarged the cavalry until it was as big as the chariot force.

To deal with the ever-present problem of rebellions, Tiglath-Pileser introduced deportation; he would remove the entire population of a troublesome area and send them to some other province, while Assyrians and conquered peoples from elsewhere moved in to take their place. The idea behind this final solution was to break up ethnic groups, and with them their will to resist. This cruel policy, like the atrocities, had the opposite effect: it did not prevent rebellions from breaking out and it led to a general dislike of the Assyrians everywhere. In the next century a Babylonian civil servant from Nippur dared to write to King Esarhaddon, "The king knows that all lands hate us on account of Assyria."

Nowadays we believe that the Assyrian army was just as good as the Roman army would be, centuries later. Both armies had the best equipment in their day, and were better trained and more disciplined than any other force. In a one-on-one fight, the Assyrians, like the Romans, usually won. However, the Roman Empire lasted longer and it was more stable; the Romans weren't in danger of a civil war destroying the Empire, every time they got a new emperor. The difference was in how they administered the areas they conquered. Whether they appointed governors like Pontius Pilate, or used client kings like the Herods (see Chapter 7), the Romans were far more effective administrators.

The campaigns of Tiglath-Pileser went forth in all directions, leaving no stone unturned. First an expedition to the south drove the Aramaeans away from Babylon and reminded the Babylonians that Assyria was still in charge. So far we haven't talked much about Babylon in this chapter, so let's take a brief time-out to see what Assyria's old rival was doing. The current king, Nabonassar (747-734 B.C.), was the first native ruler Babylon had seen in many years. He was having trouble establishing Babylon's authority over the rest of central and southern Mesopotamia, due to unruly Aramaeans, Chaldeans, Elamites, etc. Consequently he was willing to play second fiddle to the Assyrians, if that meant Assyria would do the fighting for him. At any rate, Nabonassar appears to have been more interested in intellectual pursuits; in the past, Babylon had a reputation as a center of knowledge, and under Nabonassar it became a center of knowledge again.

The main reason why Nabonassar is worth remembering is because he reformed the calendar. Later on, when the people of Judah were taken in captivity to Babylon, they would adopt this calendar. You can see the Jewish calendar's Babylonian origins in the Babylonian names of the months; even the month of Tammuz has kept its name, though it comes from a Sumerian king who was declared a god (see Chapter 1, footnote #3). Also, this is the first calendar on record to count from a fixed year, in this case 747 B.C. As far as we can tell, before this time every city-state or kingdom counted dates according to the reign of the current monarch, so whenever they got a new king, the year number went back to 1. Classical-era authors familiar with astronomy, like Berosus, Hipparchus and Claudius Ptolemy, wrote about an "era of Nabonassar" beginning in 747 B.C., so according to the Babylonian calendar, the death of Alexander the Great, which we date to 323 B.C., occurred in the year 425. When the Greeks and Romans got calendars, they counted from earlier fixed years (776 B.C. for the Greeks, 753 B.C. for the Romans), but their calendars were developed later, and were probably inspired by the Babylonian model.

Now let's return to the narrative. Once he was done with Babylon, Tiglath-Pileser charged to the west and defeated the Neo-Hittite and Aramaean city-states in Syria, and their protector, Sardur II of Urartu, who fled ingloriously on a mare. The surviving princes, including Rezin of Damascus, Menahem of Israel(20), and a certain Zabibe (the "queen of the Arabs"), rushed to bring presents and tribute. Three campaigns to the east conquered the Medes, and in 735 B.C. the capital of Urartu was besieged, but not taken.

A new anti-Assyrian coalition formed in the west, forcing Tiglath-Pileser to return there. This time the Philistine prince of Ashkelon was killed in action; his counterpart in Gaza "fled like a bird to Egypt." Ammon, Edom, Moab, Judah, the Greeks of Cyprus and another Arab queen named Shamshi paid tribute. Two years later King Ahaz of Judah, besieged by both Israel and Damascus, called for help; Tiglath-Pileser annexed Damascus and half of Israel, and put a puppet named Hoshea in charge of the latter. In 729 B.C. he went to Babylon and killed a usurper who had taken the Babylonian throne, after the reign of Nabonassar had ended. Henceforth, there would be no separate Babylonian king; the king of Assyria was the king of Babylon, too. At the following New Year festival Tiglath-Pileser "took the hand of Bel (Marduk)" and was proclaimed king of Babylon under the name of Pulu (Pul in the Old Testament). One year later he died, or to use the Babylonian expression, "he went to his destiny."

When the next king, Shalmaneser V (727-722), was crowned, Israel refused to pay tribute. Assyrian troops surrounded Samaria on schedule, but Shalmaneser was assassinated while the siege was still in progress. The killer who took his place, Sargon II (722-705), founded Assyria's last ruling dynasty and lived up to his Akkadian namesake. At the beginning of his reign he finished what Shalmaneser V started, by capturing Samaria. The northern tribes of Israel were relocated beyond the Euphrates and disappeared from history, becoming the "Ten Lost Tribes." In their place came other unfortunates, who mingled with the few Israelites left behind and produced a half-breed people, the Samaritans of New Testament times.

Outside Assyria's borders, Egypt and Elam grew increasingly nervous of the Assyrian advances. They lent men and weapons to rebels in the nearest provinces, and thus joined Sargon's list of enemies. The pro-Elamite rebel in Babylonia was one Marduk-apal-idina, called Merodach-Baladan in the Old Testament. When Sargon came against him in 720 B.C., the Babylonians appear to have won, for Merodach-Baladan ruled the south as he pleased for another decade, backed by the current Elamite kings, Khumbanigash (743-717) and Shutruk-Nahunte II (717-699). One amusing detail: Merodach-Baladan's inscription proclaiming his first victory was confiscated from Uruk by Sargon in 710 B.C., taken to Calah, and replaced with a clay cylinder bearing a radically different Assyrian version of the event (evidently propaganda and "cold war" tactics were in use long before our time!). In the west a quick campaign from Syria to Gaza got rid of the Egyptians and their allies. In 717 B.C. he took Carchemish, and invaded Cilicia. Here the main enemy was Phrygia's Midas III, called "Mita of Mushki" in Sargon's records, and hostilities continued for a decade before Midas agreed to pay tribute.

In 716 B.C., king Sargon II of Assyria moved against Mannea. Here the ruler Aza, son of Iranzu, had been pro-Assyrian, and was murdered by a conspiracy in his court that had been hatched in neighboring Urartu. Sargon couldn't let this go unpunished, so he marched in, conquered the Mannaeans, killed the conspirators, and installed Aza's brother Ullusunu as governor of the new province. As soon as he left Mannea, however, Ullusunu abruptly switched sides, becoming pro-Urartu. Sargon quickly returned and burned down Izirtu; Ullusunu fled into the mountains, but feeling that he couldn't escape even there, returned and begged for a pardon. Incredibly, Sargon granted it, and even let Ullusunu resume the governorship; perhaps he felt Ullusunu had been bullied by Rusas (735-713), the king of Urartu, into becoming a turncoat. After this, the Assyrians used Mannea to breed, train and trade horses.

Now that Assyria had stripped Urartu of its allies and vassals, it was time to invade Urartu itself. This proved to be Sargon's toughest campaign, and it got underway in 714 B.C. The march northwards through the mountains of Kurdistan was especially hard, and the geography of the region favored the enemy. However, the Assyrians fought their way around Lake Urmia and captured Urartu's sacred city, Musasir, and as the Elamites had once done to Babylon, they took away the national god, Chaldi. When King Rusas heard the news, he committed suicide. Urartu lingered on after that for just over a century, but it was never an important state again. Thousands of Urartians were deported to an area along the Persian Gulf that the Assyrians named Kaldu(21); henceforth the inhabitants of the region were known as Chaldeans.

The northern campaign also nipped a Median revolt in the bud. Sargon's records mention that an individual named Daiakku had succeeded Ullusunu as governor of the Mannaean province (Herodotus called him Deioces). He chose to back Urartu, was captured, and deported with his family to Hamath in Syria. His spirit lived on, though; the Medes remembered him as the founder of their state, and under his son Khshathrita (Phraortes), the Median tribes were united.

Now that he had won in the west, east and north, Sargon was ready to march south, for a rematch against Merodach-Baladan. This time he succeeded, defeating the Babylonians and their Elamite allies in 710 B.C., and again in 708; Merodach-Baladan was forced to flee to Elam.

Victorious everywhere, Sargon was at the peak of his career. All attempts to stop him had failed, leaving Assyria stronger than ever; places as far away as Cyprus and Bahrein were now sending tribute. At home Sargon began to build a new capital, which he named Dur-Sharrukin (modern Khorsabad). During the last ten years of his reign he built a magnificent palace, with huge stone cherubim (winged figures with human heads and the bodies of bulls) guarding the gates, and over a mile of bas-reliefs adorning the walls. However, the city was not in use for long; one year after the king finished it he went on a campaign against the Cimmerians (see below) in the Taurus Mountains, and was slain in battle. We are not sure, but it looks like Sargon's body was left on the battlefield, and never buried; to a superstitious people like the Assyrians, that would have been a very bad sign. The court abandoned his new capital, and Sargon's son and successor, the famous Sennacherib, chose to rule from Nineveh instead.

Before we continue, I would like to mention a spectacular discovery that has gotten little attention. In 1989 A.D. Muzahim Mahmoud Hussein, an Iraqi archaeologist, discovered the intact tombs of several Assyrian queens at Nimrud (ancient Calah), buried under the harem of Ashurnasirpal's palace. This came as a surprise because other archaeologists had gone through Calah for a century an a half, without finding the tombs. Moreover, we already knew that it was the Assyrian custom to bury the dead under their houses, so somebody else should have found them first; the tombs would have been picked clean of their treasures if that had happened. On top of that, these were the wives of some of the most important kings: Yabaya, the queen of Tiglath-Pileser III; Banitu, the queen of Shalmaneser V; and Talya, the queen of Sargon II. Buried with them were 80 pieces of gold jewelry (mostly crowns, rings, necklaces, earrings and bracelets), that contained semiprecious stones; together, they weighed thirty-one pounds. A fourth tomb, meant for Queen Mulisu, the wife of Ashurnasirpal II, contained the largest treasure trove of all--440 works of gold weighing a combined total of fifty-one pounds--but the Queen's stone sarcophagus was empty, while three bronze coffins containing unidentified skeletons were also in the room. The quality of the goldwork is exquisite, and of all the artifacts that have turned up in graves from the ancient world, only the treasures of Tutankhamen are more impressive. It also showed us that Calah/Nimrud remained the preferred location for the Assyrian capital until Sargon II's reign.

The discovery of the "Treasure of Nimrud" made few headlines because it was overshadowed by current events. The Iraqi government discouraged foreign journalists and archaeologists from coming to Calah, because it didn't want to deal with publicity, when the country was recovering from the recent war with Iran (see Chapter 17). Then when another Persian Gulf war broke out in 1991, it put an end to plans for further excavations. As for the treasures of the queens, they went to the chief museum in Baghdad, where they stayed until Saddam Hussein's ouster in 2003. When a wave of looting hit Iraq's museums that year, it was thought the treasures had been stolen. Fortunately they were really hidden, and turned up in a flooded bank vault a few months later, along with the treasures of King Faisal I (see Chapter 15).

Now back to the narrative. Sennacherib spent his reign (705-681) dealing with the various rebellions that broke out when he assumed the throne. Judah's Ahaz had been pro-Assyrian because Israel was anti; now promises of Egyptian aid persuaded Ahaz's successor, Hezekiah, to act otherwise. In 702 B.C. Sennacherib came to deal with this challenge, uprooting rebels along the Mediterranean coast from Sidon to Philistia. An Egyptian army that came to the rescue was stomped at Eltekeh. Then he chastised Judah, taking Lachish (Judah's second largest city) in a siege that went so smoothly that pictures of it were inscribed on the walls of Nineveh, as a model of how future sieges should look. Sennacherib locked Hezekiah in Jerusalem "like a bird in a cage," as he put it, and exiled 200,150 people; he levied so much tribute on Judah that the gold had to be stripped from the doors of Solomon's Temple to pay the bill.

Despite Egypt's defeat, Hezekiah still tried to get aid from the Nile valley. The Bible tells us his chief ally at this point was "King Tirhakah of Ethiopia" (2 Kings 19:9; Isaiah 37:9), no doubt the XXV dynasty pharaoh we call Taharqa. However, we are at 701 B.C., and Taharqa's reign was from 690 to 664 B.C.; the best way to explain this is to assume that at the time of Sennacherib's first invasion, Taharqa was a general or viceroy of Nubia, like "Zerah the Ethiopian" from earlier in this chapter. Thus, the authors of the Old Testament account may have called him king simply because they lived after his coronation, just as we might call Dwight D. Eisenhower a future president of the United States, while talking about his battles in World War II. The alliance caused the Assyrian army to march to Jerusalem, and outside the walls of the holy city a dramatic debate (recorded in 2 Kings 18-19 and Isaiah 36-37) took place between the representatives of Hezekiah and Sennacherib. What happened next is uncertain, but it must have been dreadful; according to the Biblical account an angel of the Lord went out one night and slew 185,000 Assyrian soldiers. Herodotus quoted an Egyptian account that claims a swarm of mice chewed up everything the Assyrians had that consisted of rope or leather; the Babylonian historian Berosus said a plague wiped out the army; some modern historians like Immanuel Velikovsky speculate that a meteorite blasted the Assyrian camp. Whatever it was, the Assyrians chose to say nothing about this inglorious episode.

In Babylonia the situation was far worse, because Merodach-Baladan, Sargon's old rival, refused to give up. In the year that Sennacherib came to power, he returned from exile in Elam to raise the banner of revolt in Babylon again. It was around this time that Merodach-Baladan made his appearance in the Bible, when he sent an embassy to Judah (2 Kings 20:12 and Isaiah 39:1), to congratulate Hezekiah's recovery from a life-threatening illness, and to inquire if Hezekiah was interested in fighting the Assyrians some more. Hezekiah let the ambassadors know he had the resources to help, by showing them his treasures, but he did not take part in the rebellion, which is just as well, because Merodach-Baladan failed again. Sennacherib marched on Babylon in 700 and drove out Merodach-Baladan a second time; the Assyrian king installed his own son, Ashur-nadin-shumi, in Merodach-Baladan's place.

Shutruk-Nahunte II was the last Elamite king to use the old title "king of Anshan and Susa." He was assassinated by his brother Khallushu, and then in 694 B.C. Khallushu marched into Mesopotamia, got the Babylonians to revolt, captured Babylon, killed Ashur-nadin-shumi, and reinstated Merodach-Baladan. Sennacherib returned nine months later and defeated the Babylonians near Kish, forcing Merodach-Baladan to flee once more. To escape, Merodach-Baladan put his goods, his people and his gods on boats, sailed down the Euphrates to the Persian Gulf, and then followed the Gulf's eastern shore until he came to Elamite country. Sennacherib followed him as far as the shore of the Persian Gulf, before turning back. Shortly after that Merodach-Baladan died, but there were plenty of folks left to take up his cause.

The failures of the Babylonian-Elamite alliance seem to explain why quite a few Elamite kings at this stage were murdered by their own relatives. The next assassination was done by Kutir-Nahunte, who slew his father Khallushu, only to abdicate a year later so that his brother Khumma-Menanu III (692-689) could rule. Khumma-Menanu recruited a new army to help the Babylonians in their next revolt, and together they very nearly defeated the Assyrians in a great battle at Hallule, on the Tigris. Blind with rage, Sennacherib did the unthinkable: when he captured Babylon two years later (689 B.C.) he utterly destroyed the city, the heart of Mesopotamian civilization, the "bond of Heaven and Earth." Whereas all his ancestors had treated Babylon with patience and respect, Sennacherib bragged about attacking it "as a whirlwind," and about the destruction he caused: "Its inhabitants, young and old, I did not spare, and with their corpses I filled the streets of the city." He even collected the ashes from the burnt houses and buildings, and sent them as souvenirs to loyalists; some of the ashes went to the temple of the god Ashur "in a covered jar." The gods whose temples Sennacherib had burned could not let this crime go unpunished; the priests of Sumer and Akkad predicted a violent end for the brutal king, which would be fulfilled eight years later.

Before that could happen, though, there was time for one more campaign in the west. Judah's eastern rivals--Ammon, Moab and Edom--fell to the Assyrians around 688 B.C. Then came an invasion of Egypt; the Assyrians advanced to Egypt's easternmost city, Pelusium. Taharqa fled up the Nile, and Sennacherib crowned a pro-Assyrian Egyptian, Tefnakht II, as his vassal; he may have been descended from the XXIV dynasty ruler named Tefnakht.

The Rise of Lydia

On their northern frontier, the Assyrians received unexpected help from the barbarian tribes migrating across the Caucasus. The first to arrive, the Cimmerians, came in 720 B.C., in time to help Sargon II during his campaign against Urartu. Two things motivated the Cimmerians to move: a chance to do some easy raiding, and pressure from a stronger tribe behind them, the Scythians. We credit the Scythians with inventing the horse-riding nomad culture that dominated the central Asian steppes for most of history afterwards. The Cimmerians were probably still using chariots when first attacked by the Scythians, but their success after this argues that soon they were also fighting Scythian-style on horseback.

After this Urartu was a vassal state to the Assyrians, and the Assyrian-Urartian alliance was too strong for the Cimmerians, so the nomads were directed westward into Anatolia, where the main target was Phrygia. They destroyed Gordium in 696 B.C.; King Midas III reportedly committed suicide by drinking bull's blood when he saw that the end of his kingdom had arrived. Then everyone else in the area was hard hit as well. Finally in 679 B.C., Assyria's Esarhaddon inflicted a crushing defeat upon them in the gorges of Cilicia, ending the Cimmerian threat to everyone except the folks in Anatolia.

In western Anatolia a new kingdom named Lydia replaced the Phrygians. Until now Sardis, the Lydian capital, was just another city-state in the region. According to Herodotus, it had existed for 505 years, and seen twenty-two kings, but it had never been very important. That changed with the extinguishing of the Phrygians, which left a vacuum to fill. Then around 690 B.C. a new dynasty, the Mermnadae, took over, and Lydia's fortunes soared.

Greek writers were in agreement that Gyges, the founder of the dynasty, did it by seizing power, but disagreed on what prompted him to do it. The best-known account comes from Herodotus, who claimed that Gyges was a peeping Tom! According to him, Gyges was the favorite guard of the previous king, Candaules, and one day Candaules boasted to him about the queen's beauty. Gyges didn't respond with much enthusiasm, so the king thought he was skeptical, and told him to find out for himself: "Well, a man always believes his eyes better than his ears, so do as I tell you--contrive to see her naked." Gyges didn't want to do any such thing because the Lydians, unlike the Greeks, did not think it is proper to see a man or woman without clothes under any circumstances, but the king insisted. He suggested that Gyges go into the royal bed chamber, and hide behind the door; then when the queen arrived that night, she would undress beside a chair and go to bed, giving Gyges one good chance to see her naked before he sneaked out of the room. It would have worked, except that the queen saw Gyges sneaking out; however, she kept her mouth shut. Then the next day, she summoned Gyges on what he thought was routine business, told him what happened the night before, declared that she knew either Candaules or Gyges was behind this outrage, and gave him this choice: he could kill his master and take the queen as his wife, or he could die on the spot. Faced with possible death if he launched a coup and failed, or certain death if he didn't act, Gyges chose the former, and killed Candaules in his bed. The people of Sardis were mad enough to revolt, but Gyges placated them by letting the Oracle at Delphi, the most famous advice-giver of ancient times, decide the matter, and when asked (presumably after Gyges sent Delphi a gift), the oracle said that Gyges should be the ruler.(22)

As king, Gyges had many enemies to deal with. The nearest were the Greeks in the Ionian city-states, and all he could do regarding them was capture one of their cities, Colophon. Another danger was the Cimmerians, and that forced Gyges to call on Assyria's Ashurbanipal for aid. Ashurbanipal regarded Gyges as yet another king submitting to Assyrian authority (the Assyrians called him "Gugu"), and saw Lydia's gifts as tribute, but after the danger passed, Gyges started meddling in Egyptian politics, giving aid to Psammetich when he declared Egypt's independence from the Assyrians (see below). Consequently the Assyrians stopped supporting Lydia against the Cimmerians, and Gyges was killed when the Cimmerians looted Sardis in 652 B.C.

The next king was Ardys (678?-629 B.C.). Herodotus asserts that the Cimmerians sacked Sardis again during his reign, but this looks like a scribal error; somebody probably wrote down the previous raid twice on a manuscript, so it looked like there were two Cimmerian attacks on the capital, not one. After Ardys came Sadyattes, and the only information we have on him is that he reigned for twelve years (629-617 B.C.), and he spent the second half of his reign raiding the land of Miletus, another Ionian city-state. Presumably both Ardys and Sadyattes followed the foreign policy established by Gyges: accept the Assyrians in the east--even pay tribute, if necessary--and you will have a free hand to expand in the west. The Lydians would be much more active under Alyattes, the fourth king of the dynasty, but that's a topic for the next chapter of this work.

Like Phrygia, Lydia was fabulously wealthy. From the start the Lydians had a commerce-based economy, which traded Greek manufactured products like pottery for the raw materials of Anatolia. In the latter they were blessed, for the nearby river valleys had good farmland, the mountains had trees to provide lumber, and as we mentioned previously, there was mineral wealth, especially gold. To improve on the trade network of the Phoenicians, they had two new inventions, money and a capitalist economy. In the early days of the kingdom, they used lumps of electrum (a naturally-occurring alloy of gold and silver) as currency, stamped with pictures of animals; by the middle of the sixth century B.C., coins of the shape we are familiar with came into use. Trading with money proved to be much more convenient than estimating the value of precious metals by their weight, and was less complicated than the barter used previously, so it didn't take long for the Phoenicians and the Greeks to adopt coinage for themselves; after the Persians took over they would spread the concept of money to the rest of the known world. We can claim they invented capitalism, too, because between 650 and 600 B.C., Sardis built the oldest known marketplace--a business and industrial quarter walled off from the rest of the city, which we call the Lydian Market. Up until this time, any kind of shop was usually part of a temple or connected to the owner's house; the idea of zoning for purely residential districts had not occurred yet. Now with workshops and bazaars set aside in a separate area, cities had what the Greeks would call an agora, and what the Romans would call a forum--a place for manufacturing, trading and just plain socializing on a larger scale than what had been possible before.

Josiah the Righteous

Hindsight tells us that it would have been better for Judah if Hezekiah had not recovered from his illness. As the prophet Isaiah predicted, he lived fifteen years after he got better, and during that time, his son Manasseh was conceived and born, for Manasseh was only twelve years old when he got to wear the crown. At fifty-five years, Manasseh enjoyed the longest reign of any king in Israel or Judah, but he was as evil as his father had been good. He rebuilt all the altars and holy places to foreign gods that Hezekiah had torn down, set up an idol of Baal in Solomon's Temple, and even offered up a son as a burnt sacrifice to Moloch. The prophets warned that God would allow Judah to suffer the same fate as Israel, and Manasseh killed many of them in a wave of persecution; Jewish tradition asserts that one of the victims was Isaiah, who was placed in a hollow log and sawn in two.

Eventually Manasseh got to be so bad that the Assyrians didn't want him around anymore, and when you've been bad enough that the Assyrians don't want you around, you've been bad! Anyway, the Assyrians took Manasseh away and threw him in a Babylonian prison, where he repented of his wicked ways and was eventually allowed to return to Jerusalem. The Bible does not say whether Esarhaddon or Ashurbanipal was the Assyrian king who hauled him off, or if they did it because of any anti-Assyrian activities on Manasseh's part. One thing we know for sure: Manasseh must have been at least pro-Egyptian, because his son and successor was blatantly named Amon, after the chief Egyptian god (also spelled Amen or Amun).

Amon followed the evil pattern that Manasseh practiced in his youth. Unlike Manasseh, though, he did not get a chance to reform; after ruling for only two years, he was assassinated by his servants. However, the people of Jerusalem wanted nothing to do with the assassins, killed them in the riot that followed, and installed Amon's eight-year-old son, Josiah, as the next king.

Josiah (639-608 B.C.) was Judah's last good king. From the start, the only god that interested him was the God of his ancestor David and his great-grandfather Hezekiah. He couldn't act on his beliefs until he grew up, but once he came of age he banned idol worship, destroying all images, pagan altars, sacred poles, and even the graves of the priests who served gods other than the One True God. The high point of his reign came in his eighteenth year, when the Temple was being repaired, and in the wall the high priest Hilkiah found what he described as a "book of the law of the Lord"; we believe it was a copy of the Book of Deuteronomy. The king's scribe read the book to Josiah, and when he realized how many of the laws in the book were broken, he tore his clothes, called all the people of Jerusalem to the Temple, and read them the book from there. Those who heard it were moved as well, and after Josiah finished, everyone agreed to make a new covenant with God. The Bible tells us that the next Passover celebration was the greatest observed since the time of the prophet Samuel, four centuries earlier. But all their supplication could not stop God's judgment upon Jerusalem; all they could do was postpone it beyond Josiah's lifetime.

Assyria Triumphant

In 681 B.C., Sennacherib, while praying in a temple, met with the violent death which had been predicted for him; he was "smashed with statues of protective deities" by two of his sons. The rightful heir to the throne was not one of them, however, but Sennacherib's youngest son Esarhaddon, who fought them in a six-week civil war, that ended with the parricide brothers fleeing to the mountains of Armenia. The new monarch was the wisest of Assyria's leaders, and once his position was secure, he started rebuilding Babylon. The angry Babylonian priests had prophesied that the city would lie in ruins for seventy years, but once construction got underway they found an easy way to make the gods change their minds: "The merciful Marduk turned the book of fate upside down and ordered the restoration of the city in the eleventh year."(23) This act won Esarhaddon the friendship of his subjects in Babylonia, and they gave him little trouble for the rest of his reign. In 669 he tried to return Babylon's statue of Marduk, because the Babylonian New Year festival could not take place without it. However, an incident occurred in a village the statue passed through; people saw it as a bad omen and the statue went back to Assur.

If he could forgive, he could also punish. We already mentioned his defeat of a Cimmerian raid in 679 B.C. Then Abdi-Milkuti, the king of Sidon, revolted in 677 B.C.; Esarhaddon captured and beheaded him, deported the Sidonians, and gave their territory over to Tyre. We have a treaty with Tyre from this date, where Esarhaddon listed thirty-one kings from the Levant and Cyprus, including Manasseh of Judah, as Assyrian allies. Two years later he defeated an Elamite invasion, and scored a diplomatic victory by putting a pro-Assyrian prince, Urtaku, on the Elamite throne in Susa.(24) In 672 B.C. he returned to the Phoenician shore and captured Tyre, which had become anti-Assyrian in his absence. The ultimate source of all this trouble in the west was the pharaoh Taharqa, who during the same year had ousted Nekauba, the pro-Assyrian prince of Lower Egypt (Tefnakht II's successor). Esarhaddon now prepared to punish the Egyptians for their insubordination.

In 671 B.C., Esarhaddon led his army out of Syria and across the Sinai desert. Once they entered Egypt the campaign went swiftly: "From the town of Ishupri as far as Memphis, his royal residence, a distance of fifteen days' march, I fought daily, without interruption, very bloody battles against Tarqu (Taharqa), king of Egypt and Ethiopia, the one accursed by all the great gods. Five times I hit him with the point of my arrows, inflicting wounds from which he should not recover, and then I laid siege to Memphis, his royal residence, and conquered it in half a day by means of mines, breaches, and assault ladders; I destroyed it, tore down its walls and burned it down." In Memphis he captured Taharqa's queen and children, the women of his palace, and "horses and cattle beyond counting," all of which he sent back to Assyria. After that he chased Taharqa upstream for thirty days, imposed tribute and Assyrian governors on the whole land, and returned to Nineveh with prisoners of war and workers who had useful skills: physicians, divination experts, goldsmiths, cabinet makers, cartwrights, and shipbuilders.

The Assyrians conquered Egypt easily, but it was too far away to hold easily. Only two years later Taharqa returned for a rematch. Esarhaddon was marching to Egypt again when he fell sick in Haran and died (669 B.C.).

Esarhaddon's eldest son and crown prince, Sin-iddina-apla, had died three years before his father, in 672 B.C. That left two sons, Shamash-shum-ukin and Ashurbanipal. Esarhaddon picked Ashurbanipal to succeed him, and made the entire Assyrian court swear loyalty to the heir, because Ashurbanipal was younger and less popular than Shamash-shum-ukin. The result was a dual monarchy: Ashurbanipal became the next king of Assyria, while Shamash-shum-ukin became king of Babylon. The statue of Marduk finally came home, after a 21-year absence, so that Shamash-shum-ukin could appear with it during religious ceremonies, and Babylon was given local autonomy to keep the Babylonians happy.

Once the details of succession were taken care of, Ashurbanipal resumed the Egyptian campaign that his father's death had interrupted. In 667 B.C., Taharqa was routed yet another time, and Ashurbanipal pursued him as far as Thebes. The Assyrians were now 1,300 miles from home, in the middle of a strange land where the language, religion and customs were utterly foreign to them. Alexander the Great, in a similar position, would let the Egyptians proclaim him both pharaoh and a living incarnation of the god Amen (see Chapter 6), but Ashurbanipal, as high priest and ambassador of the god Ashur, could not even think of doing this. Since he did not have enough troops and civil servants to govern the country directly, he had to follow his father's policy: the twenty native "kings, governors, and regents" appointed by Esarhaddon were reinstated.

When he returned home, however, the governors began planning rebellion. The Assyrian officers got wind of the plot, arrested the rebels and sent them to Nineveh. All of them were executed, except for Necho I, the son of Nekauba. Necho put on such a good show of repentance that he was forgiven, "clad in brilliant garments," given a royal ring, and sent back to Egypt to be its sole governor. Then Taharqa died and was succeeded by his son-in-law Tantamani. The young Ethiopian came boldly northward, killed Necho and occupied Lower Egypt, which, however, he abandoned when he heard that Ashurbanipal was coming back with the Assyrian army. The Assyrians stopped on the Lebanese coast just long enough to retake Tyre, which had revolted in 665 B.C., and then entered Thebes a second time in 664, this time burning and plundering the main city of Upper Egypt. Twelve new governors were placed over Egypt before the king departed to deal with matters that needed his attention elsewhere.

One of those was the changing situation in Iran. In Esarhaddon's day the Scythians had pursued the Cimmerians out of Russia, made a wrong turn in the Caucasus, and came out in Iran instead of Anatolia. The Scythian presence meant that Assyria was cut off from its main source of horses, but Esarhaddon turned the situation to his advantage with an Assyrian-Scythian alliance against the Medes. In 653 B.C. Khshathrita, the king of the Medes, lost his life in an unsuccessful attack against Nineveh. The Iranian plateau fell under Scythian domination for the next 28 years.

Next door to the Medes were the Mannaeans. A Mannaean king named Ahsheri revolted against Assyrian rule in 676 and 660 B.C., against Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal respectively, but the revolt was put down each time. Ahsheri was succeeded by the last Mannaean king, Ualli, who bought off the Assyrians by sending his son to be a hostage in Nineveh, and his daughter as a wife for Ashurbanipal's harem.

South of the Medes and Scythians was the Elamite realm. Ashurbanipal once sent wheat to Elam during a famine, but the Elamite king Urtaku later changed his mind about the Assyrians, and died while attacking Mesopotamia in 664 B.C. The next king, Tempti-Khumma-Inshushinak (Teumman for short), was defeated and killed at the Battle of the Ulai River (653 B.C.), and Ashurbanipal divided Elam between two different members of its royal family, who ruled from the towns of Hidalu and Madaktu. Elam was never again a united kingdom after this, and the latter Elamite kings that we know anything about had short reigns, a good sign that the land wasn't doing well.

In 655 B.C., a governor of Egypt, Psammetich I, the son of Necho, deposed his rivals, recruited Ionian and Carian mercenaries from Lydia, and raised the flag of independence. Normally the Assyrians would have crushed such an upstart without hesitation, but now the Assyrian army was tied up in a bloody struggle with the Elamites (see above). Ashurbanipal was forced to give up Egypt to save Iraq, and in 652 he allowed Psammetich to rule Egypt on condition that he support Assyria in future conflicts. The first of these involved the rebellious Philistine city of Ashdod. Psammetich sent an Egyptian army to Ashdod, but lacking the siege equipment of the Assyrians, it took 29 years to capture the city (Herodotus called this the longest siege on record).

For nearly twenty years Babylonia remained quiet, due to a need to recover from the wars and devastation of the past decades. However, relations cooled between the brothers; no doubt Shamash-shum-ukin resented his second-rate status, and like Kurigalzu in Chapter 2, life in Babylon turned him into a Babylonian nationalist. In 652 B.C. he launched a huge conspiracy to bring Phoenicia, Philistia, Judah, the Arabs, Elam and even Lydia and Egypt against Assyria. This may have been the time when the Assyrians threw King Manasseh of Judah in prison. Fortunately for the Assyrians, they discovered the plot in time to stop it; only the Chaldeans and Elamites sent troops to fight on Shamash-shum-ukin's side(25). Then Ashurbanipal moved against his brother. For three years the war went on around Babylon (651-648), until Shamash-shum-ukin lost hope, set fire to his palace and perished in the flames. Ashurbanipal put a loyal governor named Kuduranu in charge of Babylonia, and marched into the Arabian desert, conquering the Arabs in a campaign that was remarkably successful, considering the environment the fighting took place in.

The Arabs subdued, Ashurbanipal went against Elam. In 646 B.C. he sacked Susa and devastated the surrounding countryside (Susiana). Still, the war continued for a few more years. Ashurbanipal had to take some time off in 643 to punish the Urartians, who had squabbled with the Assyrians over Ubumu, a provincial capital that Esarhaddon had annexed a generation earlier. Once he showed Urartu who was boss, the current king, Sardur III, quickly sent tribute and resumed the policiy of avoiding conflict with the Assyrians. Finally Ashurbanipal captured the last independent Elamite king, Khumma-Khaldash III (also spelled Humban-Haltash III), in 640. Then he devastated and thoroughly plundered the entire land of Elam. The clay tablet, which Ashurbanipal used to record the destruction of Elam, reads as follows:

"Susa, the great holy city, abode of their Gods, seat of their mysteries, I conquered. I entered its palaces, I opened their treasuries where silver and gold, goods and wealth were amassed...I destroyed the ziggurat of Susa. I smashed its shining copper horns. I reduced the temples of Elam to naught; their gods and goddesses I scattered to the winds. The tombs of their ancient and recent kings I devastated, I exposed to the sun, and I carried away their bones toward the land of Ashur. I devastated the provinces of Elam and on their lands I sowed salt."(26)

The rivalry between Elam and Mesopotamia, which had lasted for more than two thousand years, was finally over.(27)

"I am Ashurbanipal, the great king, the mighty king,

king of the universe, king of Assyria, king of the world's four regions,

king of kings, unrivaled prince, who, at the divine command of Ashur,

holds sway from the Upper to the Lower Sea (the Mediterranean Sea and the Persian Gulf),

and has brought under his feet all princes."(28)

At Nineveh Ashurbanipal greatly enlarged his capital and celebrated his triumph. The captured Khumma-Khaldash III was brought home and forced with another Elamite ruler, Tammaritu, to pull the Assyrian kings chariot to the Ishtar temple, in a parade that must have resembled the triumphs the Romans would stage for their conquering heroes.(29) However, he may have been even prouder of the library he built at Nineveh, which was discovered in 1849 A.D. by Sir Austen Henry Layard, a British archaeologist. At the last count, the library contained 30,943 clay tablets, including the best preserved copies we have of the Gilgamesh epic, the Babylonian creation story (Enuma Elish); Ashurbanipal even claimed to have some texts which were written "before the flood" (Noah's flood).(30) We also have a letter from Ashurbanipal to the Babylonian governor Kuduranu, which gives us an idea how he acquired that collection: "Seek out and send to me any rare tablets which are known to you and lacking in Assyria."

To Ashurbanipal, the whole world was now defeated and under his rule. Nineveh was overflowing with tribute taken from other cities, and the Assyrians were feared from the shores of the Aegean Sea to the sands of Arabia. Never did Assyria look so invincible, but there were clouds on every horizon. Egypt and Media were lost forever; Elam was destroyed; Babylonia was devastated and no longer loyal; the Phoenicians were losing their commerce to the Greek competition. The Scythians, supposedly allies, marched and raided through the Assyrian empire as if it were their own, advancing as far southwest as Israel before the Egyptians bought them off.(31)

The Assyrian army was exhausted, bled white from a century of unending warfare. Despite appearances, Assyria was now weaker than it had ever been. You can call 639 B.C. the year when the Assyrian Empire peaked, because records abruptly stopped after that; we have almost no records for the last twelve years of Ashurbanipal's reign (639-627). We used to think the lack of records meant the empire was peaceful and happy; now it seems more likely that new revolts broke out during that time, and the reports of those revolts were destroyed, either erased by Ashurbanipal himself, or lost in the conflagration that marked the empire's last years.(32) One record that we do have is a prayer from the king, showing a remarkably different attitude from the triumphal inscription above:

"I did well unto god and man, to dead and living. Why have sickness and misery befallen me? I cannot do away with the strife in my country and the dissensions in my family; disturbing scandals oppress me always. Illness of mind and flesh bow me down; with cries of woe I bring my days to an end. On the day of the city god, the day of the festival, I am wretched; death is seizing hold upon me, and bears me down. With lamentation and mourning I wail day and night, I groan, 'O God! Grant even to one who is impious that he may see thy light.'"(33)

Because of that prayer, and because only the city of Haran has records mentioning Ashurbanipal after 631 B.C., some historians have suggested that the burdens of rule had become too much for the king, and he abdicated a few years before his death to become a priest in Haran. Whether or not he did, the long-term result was the same. By the time of Ashurbanipal's death in 627 B.C., the revolts were more than his successors could handle, and in less than twenty years the empire collapsed.

This is the End of Chapter 3.

FOOTNOTES

16. At this point, the Aramaeans were the most widespread people in the Middle East. Outside of Syria, they made up a significant portion of the Fertile Crescent's population, especially in Babylonia. In addition, the Aramaeans were fine traders, and they established a land trading network that mirrored the network the Phoenicians had on the seas. For these reasons, around 800 B.C. Aramaic replaced Akkadian as the international language of diplomacy. It would still be widely used for centuries after the Aramaeans were gone; it became the official language of the Persian Empire; in the time of Jesus the Jews used it for everyday conversation, while the Gentiles used Latin or Greek. It is still used today in the liturgies of the (Nestorian) Church of the East. Another Aramaean contribution to us is their alphabet; cursive forms of it eventually became the Arabic and Farsi (Persian) scripts.

17. Semiramis was credited with inventing pants. Supposedly it was done on a campaign into the Zagros mountains, so that her enemies would think she was a man. Whether the invention was for disguise or to keep warm in cold places, most historians will tell you that the Scythians were the first people on record to wear trousers of any kind, because they were far easier to handle on horseback than robes. At any rate, it was men, and not women, who wore them for most of history; hence the early twentieth-century expression about a strong-willed woman "wearing the pants in the family." Other legends claimed that Semiramis invented eunuchs (compare this with Chapter 5, footnote #5), used and discarded men like an ancient Catherine the Great, and even invented a male chastity belt to keep her son from fooling around with women while she was out of town! As with the pants legend, I don't take these stories seriously, either.

18. We noted in Chapter 2 that "Amazon" is a word of Anatolian origin. Though the Amazons figure prominently in Greek myths, so far no civilization has been found that was dominated by female warriors. Most Greek authors put the Amazons somewhere in Anatolia; Herodotus thought they settled in Ukraine, where they intermarried with the Scythians and became the ancestors of the Sarmatian tribe; Diodorus Siculus believed they came from Libya. Recently it has been suggested that some Mycenaean or Archaic-era Greeks saw beardless Asiatic warriors at a distance, and because Greek men almost always have beards, they thought they were looking at an army of women. If that is the case, then the Hittites become a candidate for the Amazons, because in their art they portrayed themselves as beardless.

19. Robert Graves, The Greek Myths, 1955, §83d.

20. Tiglath-Pileser imposed a staggering tribute on Israel: a thousand talents of silver. This works out to more than thirty-three tons, or 3,600,000 shekels, roughly $16.98 million in 2010 dollars. In this era, when the heads of banks and corporations make equivalent salaries, and governments talk about budgets in the billions or even trillions, $16.98 million does not sound like much. Keep in mind, though, that the average price for a slave in the early iron age was fifty shekels, so forcing Israel to pay what works out to the cost of 72,000 slaves was enough to start that kingdom on a death spiral, from which it did not recover.

21. The origin of the name Kaldu is uncertain, but it could mean "land of Chaldi," referring to the Urartian god by that name. Nowadays the area is known as Kuwait.

22. Plato told a different story about Gyges. In Book 2 of The Republic, he claimed that Gyges was originally a shepherd. One day an earthquake opened a cave in a mountain, and Gyges was the first to find it. The cave turned out to be the tomb of a giant, and the corpse wore a golden ring, which Gyges took. The ring had the power to make its wearer invisible. When Gyges learned how the ring worked, he used it to seduce the queen, then with her help he murdered King Candaules and became the new king of Lydia. Like he did with the Atlantis legend, Plato was teaching a lesson in morals; with Gyges the lesson was that morals disappear when men have no fear of being caught or punished. If the story sounds familiar, it should; the ring of Gyges gave some ideas to J. R. R. Tolkien.

23. The cuneiform symbol for 70 looks like 11 when flipped over, just as our figure 9 becomes a 6.

24. There was a revolt at the beginning of Esarhaddon's reign by Nabu-zer-kitti-lisir, the governor of the Sealand province along the Persian Gulf; he was both an ethnic Elamite and the son of Merodach-Baladan. The governor besieged Ur, failed to take it, and fled to Elam, but instead of giving him refuge, "the king of Elam took him prisoner and put him to the sword."

25. Next to Sammuramat/Semiramis, the most important woman in Assyrian history was Na'qia, the queen of Sennacherib and a power behind the thrones of Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal. Na'qia probably started out as a concubine, because her name is western Semitic in origin; she could have been Aramaean, Phoenician or even Jewish. Later she was given an Akkadian name, Zakutu. At any rate, she rose to become the chief wife, though Sennacherib had to keep the other women around for political reasons. She was the reason why Esarhaddon became Sennacherib's heir (he was her son, while Esarhaddon's brothers had other mothers), and the other sons probably killed Sennacherib over the succession. One generation later, she became a kingmaker again; Ashurbanipal was her favorite grandson. All that was enough for a spectacular career, but it also appears that Na'qia/Zakutu capped it by thwarting some of Shamash-shum-ukin's plots, before he launched his rebellion.

26. Editors of Time-Life Books, Persians: Masters of Empire, Alexandria, VA, Time-Life Books, 1995, pp. 7-8. From the Lost Civilizations series.

27. We are done talking about the Elamites, but they remained a distinct people for another century or two. Elam was still divided into city-states, which didn't amount to much; their kings tried to look impressive by reviving the title they used in happier times, "king of Anshan and Susa," though Anshan was now occupied by the Persians. During the 120 years after Ashurbanipal's last victory they were vassals first of the Assyrians, then the Babylonians, and then the Persians. Darius I deposed the last Elamite king in 519 B.C., as part of his work to consolidate the Persian Empire. However, the Elamite language remained widely used at this point, since it was one of the three languages Darius used in the Behistun inscription. This tells us that the Elamite people hadn't yet disappeared at this late date. Finally, when the Parthians took over in the second century B.C., the name they gave to their southwestern Iranian province, Elymais, reminds us of the ancient kingdom that once existed there. Modern historians divide the last period of Elamite history into three parts, which they call Neo-Elamite I (970?-770), Neo-Elamite II (770-646), and Neo-Elamite III (646-519).

28. One of Ashurbanipal's boastful inscriptions. From Daniel David Luckenbill, Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1926-27, Volume 2:323.