| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of Europe

Chapter 9: TRANSITION AND TURMOIL, PART I

1300 to 1485

This chapter is divided into two parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

Part II

| The Failure of Greenland | |

| The Hundred Years War Resolved | |

| The End of the Byzantine Empire | |

| Nice Knowing You, Burgundy | |

| The Wars of the Roses, Phase 1 (1455-65) | |

| The Wars of the Roses, Phase 2 (1469-71) | |

| The Wars of the Roses, Phase 3 (1483-85) | |

| Showdown in Spain | |

| Renaissance Italy | |

| The Early Renaissance Men | |

| Economics at the End of the Middle Ages | |

| The First Age of Invention |

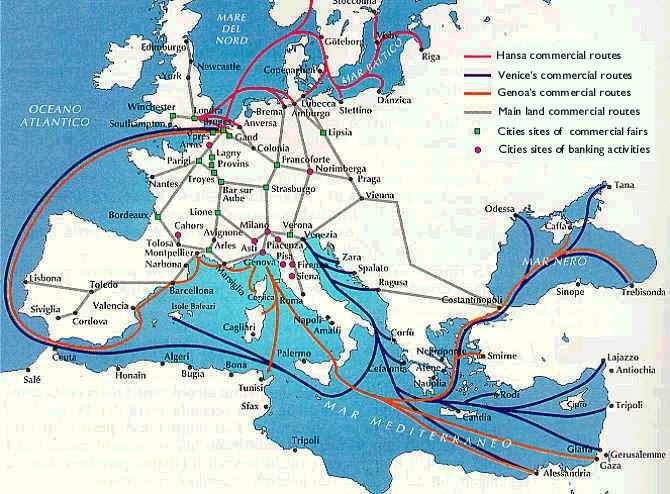

The Hanseatic League and the Merchants of Venice

In Chapter 8 we noted that the cities of Germany took charge when Denmark lost control of the Baltic trade in the 1220s. Based in the Baltic port of Lübeck, a collection of German merchants grew into the Hansa (group), the great trading cartel that controlled commerce in the Baltic and North Seas for much of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The merchants worked together as early as 1161, though they weren't formally organized as the League van der düdescen hanse ("of the German Hansa") until 1358. At its height, the League had seventy members, including every German town along the Baltic shore and a lot of inland German communities. Novgorod, the only Russian city to escape the Mongol devastations, belonged to it; so did the Swedish port of Visby, though not the rest of Sweden. In fact, Visby served as the Hansa's meeting place before the merchants moved to Lübeck. The Hansa also had major offices in London and Bergen, because it did a lot of business there. Its main enemy was Denmark, and like OPEC in the twentieth century, its principal weapon was the boycott.

The Hansa was successful because it had bigger ships. The Danes were still using the Viking-style knarr, a shallow-drafted open boat designed to carry raiders. In the late twelfth century the Germans introduced the cog, a round-bellied, fully decked vessel. Cogs couldn't be dragged onto a beach, but they could carry five to ten times as much (150 tons), while costing little more to run. Scandinavian sailors couldn't compete with this; they still caught and salted herring in the Baltic and cod in the Atlantic, but their fish were now marketed by the Hansa.

Besides fish, the Hansa carried and sold the usual trade goods of northern Europe: wax, furs and woolens. Even so, the cogs had room for some new items, like Swedish copper and iron, or Prussian wheat and barley. The Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights, himself a member of the Hansa, now became the greatest grain merchant in the world; when cargoes of his grain reached the West, it caused a significant price reduction.(1) Even more important in the long run were the English exports; England began to ship coal from Northumberland around this time. The British Isles and the Low Countries had been burning coal for many years, but it was only after Marco Polo reported large-scale use in China that people realized coal was worth selling to people who didn't live near the mines.

The Hanseatic trading network is an excellent testimony to the energy and initiative of medieval Germany. However, by Italian standards the Hansa was a minor-league player. Genoa, Milan, Venice and Florence each did ten times as much business as Lübeck. While Germany's economy was growing, so was Italy's, and the Italians remained ahead because they started so much earlier.

Besides the previously mentioned advantages of location and an advanced economy, Venice also had a powerful tool in the form of medieval Europe's largest industrial complex, a shipyard called the Arsenal (from the Arabic dar-sina'a, meaning "house of industry"). Founded in 1104, it was enlarged several times after 1300, until it sprawled across 80 acres and employed 16,000 men. The Arsenal dispatched Venice's commercial fleets, had storerooms with arms, armor and saddles for thousands of soldiers, and had a foundry for making cannon for the war galleys. Even so, Venice managed to keep the Arsenal's activities secret from most who didn't work in there, by surrounding it with high walls and twelve watchtowers.

The Venetians demonstrated the Arsenal's worth when King Henry III of France, a much-needed ally against the Turks, paid a state visit in 1574. City officials showed Henry the laying of a ship's bare keel in the morning, and twelve hours later they brought him back, so he could see the finished ship launched as a full-rigged galley. The king was impressed, and the alliance was assured.

In the sphere of finance the Italians were the masters until the Dutch took their place in the sixteenth century. We already mentioned in the previous chapter how the Italians led the way in re-introducing money to medieval Europe. Italian moneylenders also introduced banking practices to Europe; in fact, the word "bank" comes from banchi, the Italian word for the cloth-covered counters they used for doing business. They probably learned about banking from somebody in the Middle East, either the Arabs or the Knights Templar. At first their most important customer was the Papacy, the only medieval organization besides the Byzantine Empire that consistently had lots of money. There were some sticky questions over the issue of banks charging interest ("usury"), which the Church had long prohibited, but nobody could find a profitable way to manage banks and investments without it, so priests and popes learned to look the other way, especially when bankers made donations to the Church or to charities. The pope's equivalent of the Internal Revenue Service preferred to employ Italian tithe collectors, and that alone kept plenty of Italians involved in banking, to the extent that even the North Sea trade was largely financed by them. By the early fourteenth century they had a banking network that stretched from London to Tabriz (the capital of Persia under the Mongols). Italian communities abroad were described as either Oltramonte (over the Alps) or Oltramare (overseas), while banking houses like the Bardi and Petruzzi of Florence had more money than most kings. In post-feudal Italy, money transformed values and became a new virtue, celebrated in poetry:

"Money makes the man,

Money makes the stupid pass for bright, ...

Money buys the pleasure-giving women,

Money keeps the soul in bliss, ...

The world and fortune being ruled by it,

Which even opens, if you want, the doors of paradise.

So wise he seems to me who piles up

What more than any other virtue

Conquers gloom and leavens the whole spirit."(2)

The new industry of finance made new demands on those who practiced it. The most important requirement was education, and this education had to be purely secular, not directed toward service in the Church. Maybe reading, writing and the ability to do math were optional in most industries, but to use the newly invented system of double-entry bookkeeping, they were absolutely essential. In addition, the complexity of the new society required more lawyers, and as they studied law, they turned to the precedents written down by Roman and Greek authors. Thus Italian education encouraged interest in the classics and prepared its students for the intellectual outburst of the Renaissance.

Soon other merchants were imitating the organization of the banking houses. For much of the Middle Ages trade was handled by individual peddlers, who wandered from market to market or gathered in towns for trade fairs. Now the most successful merchants established trading companies, and used their profits to build more ships, create new industries like mining, or set up offices abroad. Near the end of this chapter we will look at the most successful of these corporations, that of the Medici family in Florence.

The Italians also became producers in the textile trade. Before the 1220s, the cloth they made was only good for local sale. Gradually it got better, and by the 1320s Italian fabrics were of a quality that could compete with the best products of Flanders and the Levant. The raw materials had to be imported; wool from England, cotton from Egypt, and silk from Persia.(3) Fortunately when the weavers were done, their Florentine woolens, Milanese fustians and Lucchese silks were worth enough to more than cover the cost. By itself, the Medici company produced enough cloth to employ 10,000 textile workers in 300 factories.

The disappearance of the pro-Christian Mongols in the 1330s and the arrival of the uncooperative Ottoman Turks made Mediterranean trade more risky and less profitable. The sea routes remained fairly safe, though, so long as Venice and Genoa had their string of island bases and Constantinople held open the gateway to the Black Sea. Each Turkish victory made the situation more precarious for Christendom, but Genoese and Venetians continued to fight each other bitterly; they never combined to stem the advance of Islam. Their long struggle reached a bitter climax in 1379-80, when the Genoese laid siege to Venice, only to be thrown back into the sea. Genoa had played her best card and never again did Venice come so near to defeat at the hands of her rivals. In the fifteenth century Venice annexed much of the north Italian plain, an enterprise that safeguarded her Transalpine route to Germany and provided enough farmland to keep her fed, but it also involved Venice in the perpetual and debilitating wars between the Italian city-states that she had previously sat out.

The picture painted so far in this section is a rosy one, but the late medieval economy did have some serious failings. First of all, the creation of the Italian textile industry caused the Flemish one to start declining around the same time. Second, they could do nothing about political instability to the east. The collapse of the Mongol Ilkhanate disrupted the silk trade, forcing the Venetians and Genoese to pull their agents out of Persia in the late 1330s.

Finally, the replacement of feudalism with capitalism brought new risks, which even educated people had trouble understanding. In the past, economic crises were usually caused by natural disasters like drought, a really bad winter, earthquakes and volcanoes; "unnatural disasters" were limited to wars and rulers demanding too much from their subjects (either taxes or labor). Now, however, the economy could also crash because of bad numbers in someone's ledger, like interest rates and the size of a debt. You may have heard that the Great Depression of 1929 was caused by overvalued stocks, and the Great Recession of 2008 was caused by too many subprime mortgages; in that sense, the Florentine banking collapse was the first modern recession/depression.

What happened was that the Bardi and Peruzzi banking houses had made a number of bad loans, especially to Florence, Naples and most of all, England. England's King Edward III built up a mountain of debt to finance the Hundred Years War, and when he realized that he was not going to win the war quickly, and that a large part of his income was going to payments on his debts to the unpopular foreign bankers, he repudiated the debts (1343). The Bardi and Peruzzi instantly lost 1.5 million gold florins because of the king's default, causing them to go bankrupt, and when they closed their doors, Italians who had accounts with the banks lost the money they had deposited, too. And because some of those account holders were farmers, a widespread famine began in 1345. All this was a bitter blow to Florence, the soon-to-be headquarters of the Renaissance, but something worse would soon make everyone forget about it (see below).

Scotland vs. England

Life was no bed of roses in medieval Scotland. The country was backward and off the beaten path; the climate was cold and wet; the soil was poor; the Scottish clans fought almost constantly, especially in the Highlands, where resources were scarce. Even the kings and queens had it rough--so rough, in fact, that they might as well have been peasants. In Chapter 6 we noted that a third of the Byzantine emperors met violent deaths. Well, in Scotland the probability of an unpleasant end was even greater. For the 43 Scottish monarchs between the original unification of Scotland in 843, and the final union with England in 1603, the scorecard reads as follows:

- 2 of the earliest had reigns so short that we know little besides their names--not a good sign.

- 15 were killed in battle, at the hands of Vikings, Englishmen or other Scots.(4)

- 4 were assassinated.

- 4 spent at least a year in prison, which could range from house arrest in a drafty castle to a hellish cesspit of a dungeon.

- 2 more, James III (1460-88) and Mary Queen of Scots (1542-67), were executed. Mary arguably had the worst biography of them all.

- 2, John Balliol and his son Edward, were defeated, deposed and forced into exile, which in those days didn't mean spending your last years in a fancy overseas hotel, as is the fate of today's ex-dictators.

- 2 died of natural causes, but at too young an age. Malcolm IV "the Maiden" (1153-65) lived to be 23, and Margaret "the Maid of Norway" (1286-90) checked out even sooner, when she was only eight.

- Constantine II (900-943) was so humiliated by the battle of Brunnanburh (see Chapter 7), that he eventually abdicated and became a monk.

- Edgar (1097-1107) was unmarried, childless and unpopular when he died at the age of 33. His submissive attitude to England, and his recognition of Norway's occupation of the Western Isles (the Hebrides and Isle of Man), led to an insulting nickname, "the Peaceable."

- Alexander III (1249-86) took back the Western Isles from the Norse in 1266, but all his children died before him, and at the age of 45 his horse carried him off a cliff. How embarrassing.

- Robert the Bruce saw most of his family killed by the English before the battle of Bannockburn, where he became Scotland's national hero (see below). Afterwards he suffered from poor health, and died of leprosy in 1329.

However, Robert did manage an El Cid-style posthumous victory. What remained of his body was buried in Dunfermline Abbey, but he had always wanted to go on a crusade, so on his deathbed he told his friend James Douglas to take his heart on a war against the enemies of Christ. Douglas had the heart sealed in a silver box, and led a unit of soldiers to Spain, the nearest place that had Moslems to fight. Sure enough, they found a battle taking place between Christians and Moors; Douglas threw the box into the middle of the fracas, charged after it, and the rest of the troops followed. Though the Scots won the battle, Douglas was killed. The survivors recovered the heart, returned to Scotland, and buried the relic in Melrose Abbey, where it lay until a team of archaeologists discovered it in 1996. - Robert II (1371-90) didn't get the short end of life's stick, but was boring and ineffective. When England invaded in 1384 and 1385, he was nearly seventy years old, and too ill to help the Scottish barons stop those invasions. Thus, he missed his best chance to be remembered as a heroic king like the first Robert, and after that, his son Robert III had to run the country for him.

- Robert III (1390-1406) was left crippled and bedridden by a horse's kick in 1388, and consequently was never healthy enough to rule alone; his brother, Robert Stewart the Duke of Albany, handled administration. His son and heir, David the Duke of Rothesay, was a murderous pervert who had to be imprisoned and executed in 1402. Fortunately, he had another son, James I, whom he sent to France to keep him safe from treacherous nobles at home. Unfortunately, James' ship was captured by the English, Robert died heartbroken, and James was held prisoner until 1423.

- James II (1437-60) saw a golden opportunity in the Wars of the Roses to take back Roxburgh Castle from the English. How did it go? Not too good--he was killed when the cannon he was standing next to exploded. He was only 29.

- James V (1513-42) became king when he was only 17 months old. When he grew up, he began a reign of terror, which only ended when he made the most common mistake of Scottish kings--he invaded England. His army was routed by Henry VIII at Solway Moss, James promptly went insane, and died a month later at the age of 30. John Knox described him thus: "he was called of some, a good poor man's king; of others he was termed a murderer of the nobility, and one that had decreed their whole destruction." In other words, he was called cruel in an age when all monarchs were expected to be brutal butchers.

Anyway, those grim statistics are meant to prepare the reader for the rest of this section. Returning to the narrative, relations between England and Scotland took a dramatic turn for the worse in the late thirteenth century. The trouble began with the extinction of the Canmore dynasty, caused by the aforementioned deaths of Alexander III and his granddaughter Margaret. Thirteen Scottish nobles subsequently put forth claims to the throne, and they sent a list of their names to England's King Edward I. Technically Scotland was no longer a vassal state of England, because a hundred years earlier, Richard I had allowed the Scots to buy their independence for ten thousand marks of silver. Still, Edward was happy to get involved, since his campaign against the Welsh had gone so well. The thirteen claimants were then reduced to three, all descendants of David I: John Balliol, Robert the Bruce and John Hastings. Edward chose John Balliol, thinking that he could rule Scotland through him. In November 1292, Edward led an army into Scotland and proclaimed Balliol as king.

Despite their initial request, many Scottish nobles and the overwhelming majority of the Scottish people bitterly resented English interference in their national affairs. Soon Balliol came under pressure to terminate English control, so in 1295 he formed an alliance with France (France and Scotland would be allied against England for the next three hundred years), and called for a revolt against the humiliations Edward I sought to impose on himself and the country. In response, Edward crushed Balliolís army at Dunbar (April 1296), removed his former vassal, and decreed the annexation of Scotland to England. The Stone of Scone, the stone on which all previous Scottish kings had been crowned, was carried off to England as a war trophy, where it remained until 1996.

The next year saw two anti-British uprisings, led by Andrew Murray in the north and William Wallace in the south. Together they achieved a stunning victory at Stirling Bridge (September 11, 1297), where 5,000 English were killed, but Murray was also mortally wounded, so Wallace, now calling himself the agent of John Balliol, became the sole leader of the rebellion. In 1298 Edward personally led another army, and this time, reinforced with Welsh archers (this is the first time we see the longbowmen who would make such a difference in the Hundred Years War), they crushed the Scots in the battle of Falkirk. Wallace tried to continue the struggle as a guerrilla leader, and spent two years in France, trying to get the support of Philip IV, but in 1304 the other Scottish nobles submitted to English rule, and Wallace was declared an outlaw. In 1305 Wallace was betrayed to the English, convicted of treason, and given the execution of a traitor: he was tortured, hanged, cut down while still alive, and then finally disemboweled and beheaded. But in so doing, England turned Wallace into Scotland's official martyr, most recently remembered in the Mel Gibson movie Braveheart.

This wasn't the end of the matter, though. In March of 1306, Robert the Bruce, in a fit of rage, killed John Comyn, his hated rival; because he had done it in a church, he was now guilty of both murder and sacrilege. The only way to escape the law was to put himself above the law, so Robert rode as fast as he could to Scone and had himself crowned king. Most of the Scottish clergy and nobility soon rallied behind him, compelling Edward to march on Scotland one more time, but he was now sixty-seven years old and ailing, and died during the campaign. But at least he was a decent soldier; his son, Edward II (1307-27), was a disaster, more interested in sports than in war or matters of state, so Robert gained the advantage, both against pro-English nobles and against English garrisons in Scotland. Back in England, Edward II reminded people of Henry III by surrounding himself with foreign friends; the most notable of these, a French knight named Piers Gaveston, may have been the king's homosexual lover. In 1311 the alienated barons, led by Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, forced the king to appoint a committee of 21 nobles to manage the country; one year later they kidnapped and executed Gaveston.

By 1314, Robert had liberated nearly all of Scotland, and even Edward felt it was time to do something about him. However, the army he sent to relieve Stirling Castle only got as far as Bannockburn, where the English cavalry blundered into camouflaged pits and was slaughtered by Scottish pikemen. This was England's worst defeat since 1066, but Edward still refused to concede. Then Robert expanded the theater of war by sending his brother Edward to Ireland, hoping that an invasion of that island would keep the English from trying to invade Scotland again. As a diversion from the main front it worked, but as an expedition of conquest it failed; Edward Bruce knocked the Earl of Ulster out of the way, and marched around Connacht and up to the walls of Dublin, but he caused so much destruction that most Irish didn't see him as any improvement over their absentee English overlords. The adventure ended with Edward Bruce's defeat and death at the battle of Faughart (1318).

Meanwhile, Thomas of Lancaster was the real ruler of England. He and his council declared that the king could not appoint anyone or start a war without their permission. In response, Edward II made another despicable favorite, Hugh le Despenser, his chief advisor. The nobles couldn't stand Despenser, and they banished him and his son (also named Hugh) in 1321. However, they returned a year later, gathered an army with Edward, and defeated and killed Lancaster at the battle of Boroughbridge.

In 1325, Edward sent his queen, Isabella, and their son, Edward III, to pay homage to the queen's brother, King Charles IV of France; according to feudal law, the king of England was still a vassal of the French king, and this duty was required to keep the duchy of Aquitaine in English hands. While in France, Isabella had an affair with Roger Mortimer, one of Edward's disaffected barons, and they came back with an army to get rid of the Despensers and put Edward in his place. Parliament declared Edward II deposed in January 1327 (the first time they acted to remove a king), he was imprisoned, and was murdered in Berkeley Castle eight months later.(5)

Edward III (1327-77) was only a minor at this point, so his regents acted to end the war with Scotland. In 1328 they approved the Treaty of Northampton, which recognized Scottish independence. However, this Edward turned out to be a warrior king, and when he grew up he made his own attempt to reduce Scotland to vassalage. First he tried to install Edward Balliol as a puppet king (1332), but the Scots quickly threw the younger Balliol out. In response, Edward led an army northward, routed the Scots near Berwick-upon-Tweed, and occupied the southeastern part of the country. Then the Hundred Years War began, and Edward had to abandon both Balliol and his conquests, to go after a bigger prize, the chance to become king of France. With Edward gone, the Scots were finally left alone, and by 1341 they had recovered several important occupied areas, including Edinburgh.

The Babylonian Captivity of the Papacy

The late Middle Ages saw steady advances in economics, science, and technology, which opened a breach between everyday life and the practices laid down by the Church. This breach widened further because the Papacy tried to restrict the use of anything new.(6) At the same time the clergy's special exemption from taxation and temporal responsibility was condemned by kings seeking to establish a real national unity in their dominions. The political blunders of the Papacy were numerous and its crimes of corruption and nepotism were perhaps greater and certainly better publicized, but the Albigensian Crusade showed that it could handle the challenges caused by these failings. The real reason for the steady downward trend of the power and prestige of the popes after 1300 came from their inability to adapt to a changing society. Consequently the popes triumphed over the emperors of Germany in the thirteenth century, only to become servants of the French kings in the fourteenth.

The fourteenth century was not a good time for the growth of Christendom. The Spanish Reconquista had halted in the mid-thirteenth century, because Christian Aragon, Castile and Portugal now paid more attention to each other than to Moslem Granada. The Finns and Lithuanians were converted in the northeast, but in the Balkans and Asia the Catholic Church retreated. Constantinople instantly lost its Latin patriarch when the Byzantines recaptured the city in 1261. The Bulgarian patriarch had gone back to Orthodoxy a generation earlier (1235), while the new Serbian patriarch, whose first job was to crown his patron, Stephen Dushan (1346), was Orthodox from the start. The Armenian patriarch remained faithful to the Papacy, but his state was squeezed out of existence by the Mameluke sultans of Egypt (1360-75). The Orthodox didn't have much to cheer about either; though they recovered ground in the Balkans, they lost their last towns in Asia Minor to the Turks. The century began with both the Russians and Georgians paying tribute to Moslem overlords; in the second half the Byzantines became Turkish puppets.

The Papal State in Italy was an attempt to set up a domain where the pope could rule like a real king. But the popes did not stop when they won their independence; they simply would not pass up any opportunity to meddle in secular matters. Their argument was that, because mankind was sinful, everything mankind did was under their jurisdiction. Thus the Papacy got involved in matters which should not have been any of its business, like claiming as Church doctrine the false idea that the sun and the planets all revolve around the earth.

The last of the great medieval popes, Boniface VIII, met his match in two strong-willed kings, Edward I of England and Philip IV of France. From 1294 to 1298 these kings fought over the land south of the Garonne River (Gascony), because England had ruled this area previously and Philip had just seized it. To pay for this and other wars, both kings hit upon the same solution: tax the clergy. In 1296 Boniface signaled his opposition with the Clericis Laicos, a Papal bull (bulletin) threatening excommunication for any monarch who taxed the Church and any clergyman who paid the tax without Papal consent. But proclamations from Rome no longer carried the weight they used to; Europeans had seen enough abuses of Papal power to wonder if the pope really held the keys to the gates of Heaven; both Edward and Philip were confident enough of their own strength to do what they wanted, whether the Church was on their side or not. Edward answered with a decree that any clergyman who did not pay would no longer have legal protection, and all Church-owned land that did not have a house of worship on it would be confiscated by the king's sheriffs. Philip placed a complete embargo on all gold, silver and jewels going out of France, depriving the Papacy of income from the richest state in Christendom. Boniface soon gave in; he explained that he had not meant to keep priests and monks from contributing to their country's defense in times of dire need. Since the kings decided what constituted "defense" and "dire need," the royal victory was clear. After that, both kings felt good enough about the matter to end the war by letting the pope decide who got the disputed land (he ruled in favor of France).

Despite this setback, the Papacy began the fourteenth century on an optimistic note. Everyday life had been steadily improving for centuries, and there was no reason to think this would not continue. In 1300 the pope celebrated the 1300th anniversary of the birth of Jesus by proclaiming a jubilee year. An estimated two million pilgrims poured into Rome to celebrate. So many gifts and offerings were heaped upon the altars that at St. Peter's, according to one chronicler, two priests were kept busy day and night "raking together infinite money."

Pope Boniface VIII, before he became "red-faced." From Wikimedia Commons.

The smashing success of the jubilee made Pope Boniface go over the top. In 1302 he issued the Unum Sanctum, a Papal bull which went farther than the others by declaring that the entire human race was under his authority. For Philip IV, this was going too far, and he replied with an equally uncompromising counterblast. The pope prepared his ultimate weapon, a bull of excommunication, but before he could publish it, Philip struck; he sent a squad of armed men to the Pope's hometown of Anagni, with orders to bring Boniface back to France. Leading this delegation was a shrewd lawyer named William of Nogaret, a master of the trumped-up charge. William approved of any means used to get a desired testimony; his favorite technique was to strip a witness, smear him with honey and hang him over a beehive. For this case he brought a series of charges against the pontiff, which included an illegitimate election, simony, heresy, and immorality. They caught up with the eighty-six-year-old pope in his bedroom, heaped verbal abuse on him, and may have beat him up as well. Boniface was held prisoner for just over a day, until the locals rose up and rescued him. Numbed and humiliated, Boniface escaped to Rome and died a few weeks later, his bull of excommunication still unpublished.

It is worthy of note that only the people of the pope's native town cried out against this outrage. The king of France had acted with the full approval of his people; before he sent the expedition he called the Estates-General and got its consent for his rough handling of the head of Christendom.(7) Nor was there any protest in England, Germany, or even the rest of Italy. The ideas of Christendom and Papal supremacy had lost their power over the minds of men. While popes and emperors quarreled over who had the ultimate authority, ordinary people learned that they could get along fine without both.

The subsequent surrender of the Papacy to France was swift and complete. Boniface's successor only lasted for two years, and Rome slid into lawlessness. Because it wasn't safe to go to Rome, the cardinals met in Perugia, and they elected a Frenchman, the Archbishop of Bordeaux. This pope, Clement V (1305-14), accepted the Papal crown in Lyons and refused to go to Italy, so in 1309 King Philip set up a new headquarters for the Papacy at Avignon, in the southeast corner of France. The Papal Archive, probably the largest library in western Europe at this time, was moved from Rome to Avignon as well. Because he never left France, Clement acted like a tool of the French king; other events of his reign included voiding the Unum Sanctum, and the purge of the Knights Templar (see the previous footnote). After Clement the next six popes, also French citizens, followed his example and moved to Avignon. Avignon grew from a small town to a city of 80,000, with an immense clerical bureaucracy and a fine Papal palace. In 1357 a great wall was built around Avignon, to keep out the mercenary companies that were running around loose in both France and Italy at this time. But during this seventy-year period the popes seemed to be an administrative authority rather than a spiritual one; the voice of the Vicar of Christ just didn't sound the same when it was headquartered somewhere besides Rome. Moreover, in the past the popes had insisted that each bishop should stay in his diocese, the district of land where his authority lay, and since one of the pope's titles was "Bishop of Rome," it now looked like the pope wasn't keeping his own rule. Finally, the popes could have used their move away from Rome as a first step toward cleaning up the Church, but instead they quickly made Avignon as decadent and sinful as Rome had been. Later Martin Luther would appropriately call this time "The Babylonian Captivity of the Papacy." Meanwhile, Europeans turned their attention to new problems.

The Hundred Years War: From Sluys to Crécy

One of these troubles was the Hundred Years War between England and France. The name of this conflict is convenient to remember, but inaccurate; for one thing, the war actually lasted 116 years (1337-1453). Furthermore, the war was not continuous but five separate campaigns fought over the same issues, with uneasy truces between them, rather like the Arab-Israeli conflict of our own time.

In the early fourteenth century, there were several disputes between London and Paris: the two kings had argued and fought over French territory, as noted already; both nations had pirates in the English Channel; the French gave military aid to Scotland, England's perennial problem to the north; both sides competed to control the wool market in Flanders. The main issue, however, was the confusing relationship between the English and French kings, now brought to the forefront because of the extinction of the French royal family, the Capetians. Philip IV's eldest son and successor, Louis X, only ruled for two years (1314-16), and when he died he left behind a pregnant queen and a daughter named Jeanne. The French were not willing to give the throne to a female(8), so the king's Great Council took charge and waited to see if the queen's baby would be a boy or a girl. It was a boy, and he is known to history books as either John I or John Posthumous. Unfortunately for the French, the infant king died five days later. The throne now passed to two short-lived brothers of Louis X: Philip V (1316-22) and Charles IV (1322-28). Neither one of them left a male heir, so with the death of Charles IV, the French picked a cousin, Philip of the House of Valois, and crowned him Philip VI. However, England's Edward III was a closer relative of the Capetians; his mother was a sister of Louis X, Philip V and Charles IV, making Edward a grandson of Philip IV. Now Edward put forth his own claim for the French crown. To the lions on his royal coat of arms he added the French fleur-de-lis.

Edward got off to a slow start; he sent an English force across the Channel to Flanders in 1338, but the first big battle didn't take place until 1340. In that year King Edward led the English fleet to the Flemish port of Sluys, where he encountered a larger French fleet, preparing to re-enact William the Conqueror's invasion of England. English archers fired a barrage of arrows at the French, making it impossible for them to attack or retreat until the English boarded them. The result was the first naval victory in English history. Most of the French ships were sunk or captured, giving England command of the Channel.

The English armies were also more effective than those of the French. With no thought of strategy, French knights charged the enemy at a mad gallop and then engaged in hand-to-hand combat. The English stopped this with the longbow; six feet long and made of yew or linden wood, the longbow shot steel-tipped arrows that were dangerous at 400 yards and deadly at 100. The usual English plan of battle called for their knights to dismount when they got to the battlefield. Protecting them was a forward wall of archers and a barricade of stakes, planted in the ground to impale enemy horses when the French launched their cavalry charges. By the time the enemy cavalry reached the dismounted knights, only a few remained for the English to take care of; the "feathered death" had done its work.

These tactics won a resounding victory for England when the two armies met at Crécy, at the mouth of the Somme River, in 1346. Again the French force was far larger (40,000 vs. 8,500), and this time the French had archers of their own--crossbowmen from Genoa--but both knights and archers were hopelessly outclassed. The English longbow could send five or six arrows per minute; during that time, the crossbowman could only load and fire one shot, which traveled half as far. The English poured so many arrows into the French that according to one witness, "they fell like snow." Meanwhile, the inept Philip VI worked hard to destroy his own army. When he saw the surviving crossbowmen retreating, the enraged king ordered his knights to kill them, though the longbowmen were still raining down arrows on both. Philip then ordered 15 cavalry charges against the English line, all of which were stopped by the arrows. The score at the end of the day: France lost 11,500, while killing only 200 Englishmen.

Another king defeated here was John of Bohemia, who became an ally of France at the beginning of the Hundred Years War, though he had recently gone blind. The blindness meant that John had no chance of winning at Crécy, and he wasn't even likely to survive the battle, but it would have been unchivalrous if he did not participate, so he told the knights around him: "Sirs, ye are my men, my companions and friends in this journey: I require you bring me so far forward, that I may strike one stroke with my sword." Thus, the king charged the English with his horse tied to the horses of his companions, and after the battle, the bodies of the king and those who directed him were all found together.

It was not only on the battlefield that the French got the worst of it; the war took place on French soil, leaving the homes of the English relatively unaffected by the conflict. Up to this time European wars had been well-behaved by our standards. All combatants followed the customs of chivalry and decrees laid down by the church, as if they were going to a football game rather than a life-and-death struggle. Civilians were never targets, and largely ignored by both sides. When fall arrived everybody went home for the winter and came back the following spring, to pick up where they had left off. Fighting did not take place on Sundays or holidays, nor would it begin until both sides said they were ready. The only battles which lasted more than a day were sieges, and a siege was something to avoid if at all possible, since the attacker often suffered more than the defender whose castle he was trying to take. But the logistics of shipping at that time meant that it was impractical to withdraw the English army across the Channel at the end of each campaign season, only to send them back to France a few months later, so the English soldiers and Genoese mercenaries learned to live off the land instead. In the process they wasted the countryside and acted like the barbarians of old. Crops and houses were burned, the land was picked clean of anything portable and useful, and the inhabitants were made penniless--if they were not simply killed.

Speaking of mercenaries, they were a new factor, one Western Europe had not seen since the fall of the Western Roman Empire. As noted in the previous chapter, English kings now excused nobles who paid a fine, instead of going to war when the king called for it. Edward III used this money to hire more new soldiers than his predecessors had done. These troops, organized into their own units, worked well enough, so long as they were paid on time and the war continued. However, when peace broke out, they weren't willing to lay down their arms just because the kings of England and France said the fighting was over; warfare was their profession, some of them didn't have homes to return to in peacetime, and in any case they were better off as bully-boys in France, than as peasants in England. Some mercenary bands wandered southeast, where they were hired by the Italian city-states or even by the Papacy; those who did not find new employers became a pestilence to the French, as noted above.

The Black Death

England was still celebrating the battle of Crécy when a catastrophe of unprecedented proportions hit Europe. From the Caspian Sea came the most devastating disease in European history. Contemporaries called it the Black Death, because of the dark skin blotches it left on victims; now we believe it was the bubonic plague. Those who caught it suffered an agonizing period of one to three days in which they coughed up blood, fell into delirium, and grew boils or lumps called "buboes" the size of eggs.

Then and now, the plague has been blamed on the Mongol hordes which had swept out of Asia and conquered Russia in the previous century. A recent DNA study (2022) traced the disease to a cemetery in present-day Kyrgyzstan, where the first plague victims were buried in 1338 and 1339. The first outbreaks reported by medieval writers were in Sarai and Astrakhan, the two main cities of the Golden Horde, in 1346. In early 1347 it reached the Genoese ports of Tana at the mouth of the Don, and Kaffa in the Crimea. The Mongols were attacking Kaffa at the time, and they employed the first known use of germ warfare; they loaded the corpses of those killed by the plague into catapults and flung them over the city walls. But microbes don't care about politics, and soon they infected both sides with glee.(9) The Mongols were forced to abandon the siege, but the defenders wouldn't have been much worse off if the city had been taken. Rats carried the pestilence on ships headed to Trebizond and Constantinople, and from Constantinople to Alexandria, Venice and Genoa. The first half of 1348 saw the plague rage across Italy, southern France, and Mediterranean Spain. By the end of the year it had swept through the Balkans, spread from Lower Egypt to Syria and the rest of North Africa, and got a foothold in the British Isles. England's turn came in 1349, Germany's and Scandinavia's in 1350. In 1351 it reached Poland, in 1352 Russia. The last major town to be hit was Moscow, where in 1353 the plague killed the Grand Prince, both of his sons and one of his brothers. This brought the epidemic back to the Volga, a few hundred miles upstream from where it started seven years earlier.

The number of victims was clearly colossal. The Italian city of Sienna, for example, reported losing 70,000 of its 100,000 inhabitants. "No one wept for the dead," wrote a resident of that devastated city, "because everyone expected death himself." In most places survivors claimed a mortality rate of 50 to 75 percent, but they rarely produced documents to back this up. One institution that did was the Church of England, and its records show that in most of the country a third of the clergy perished. Because the clergy lived under better conditions than most people in the Middle Ages, that figure is probably one of the lowest. Archaeologists excavating the trash pits of medieval East Anglia found that the amount of pottery discarded in the pits declined drastically in the mid-fourteenth century, enough to suggest that population in the area fell by 45%. Therefore, it looks like almost half of the people died in the average community. Modern estimates of the body count across Europe range from 20 to 100 million, with 25 million as the most likely figure.(10)

The French and the English were forced to take time out from their war when the plague hit them, but a few years later they were beating up on each other again; the armies were smaller but the strategies were the same. Apparently most Europeans thought that life would go back to the way it had been before. In addition, the survivors found themselves with extra land and money, because the dead couldn't take it with them.

Unfortunately, they weren't going to recover that easily. The plague germs found new hiding places in the countryside, and in 1357 a second outbreak began in Germany. It advanced slower this time, but it spread across most of the Continent during the next eight years. In areas that had been hit before, the deadliest plague germs had died with their victims, so the combination of weaker bugs and people with some immunity to the disease meant that fewer deaths occurred. However, there were still heavy casualties in areas that had escaped the first epidemic, and a new outbreak would occur about once per decade for the rest of the century, with a really bad one striking in 1400. Instead of recovering, Europe's population bumped against a ceiling of 60 million. In the Far East, the plague reached China between thirty and forty years after its first appearance in Europe; Chinese bureaucrats reported thirteen million killed there.

The damage done to society by the Hundred Years War was trivial compared to what the Black Death inflicted. So many fell victim that there were scarcely enough alive to bury the dead, and the dumping of several bodies into a mass grave replaced the standard funeral service. Many places suffered from famine because there was no one left to work the fields or bring the harvest to market. Schools, universities and other institutions broke down because of the lack of trained personnel to run them. Crafts suffered irretrievable losses because guild masters died before they could teach all their skills to their apprentices. For decades afterward, lawyers and judges were not expected to be familiar with the old unwritten laws that their fathers and grandfathers had lived by.

Many saw the Black Death as God's punishment for the moving of the Papacy to Avignon, the lifestyle of the current pope (Clement VI lived like the more extravagant Roman emperors), the Hundred Years War, and various other sins of mankind. No conqueror, not even Genghis Khan, had taken this many lives. The horror of the disaster encouraged extreme forms of behavior. As many as 25 percent of England's population did not bother to marry, not only because of the shortage of priests, but also because they did not expect to live long enough to have children. Some lost faith in Christianity completely, and became Satanists. Some spent their money on orgies, figuring that if the world was about to end, they should go out with a big party. Others went to the opposite extreme and joined the Flagellants, a new religious order whose members believed they could purify themselves of sin, and avoid further punishment, by beating themselves with leather scourges tipped with iron spikes. Superstition and mysticism increased, and people at this time had a morbid fascination for dead things; pictures and statues of skeletons and wormy corpses were common art subjects. Literature about Ars Moriendi, the art of dying, became immensely popular.

Probably the most gripping eyewitness account of the Black Death came from Friar John Clyn, a monk from Kilkenny, Ireland. Clyn wrote Annales Hiberniae (The Annals of Ireland), an Irish version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (see Chapter 7) that listed historical events relevant to him, from the birth of Jesus to 1349. We believe the book ended with 1349 because the Black Death killed him in that year. His entry for 1348 concludes with a message for future generations of humanity to continue his work, just in case this wasn't the end of the world:

"But I, brother John Clyn, a Franciscan friar, of the Convent of Kilkenny, have in this book written the memorable things happening in my time, of which I was either an eye-witness, or learned them from the relation of such as were worthy of credit. . . Expecting death among the dead, . . I leave behind me parchment for continuing it if any man should have the good fortune to survive this calamity, or anyone of the race of Adam should escape this pestilence, and live to continue what I have begun."

The Hundred Years War: Reverses and Revolts

The plague also started a generation of major social unrest. In began in France when the English recovered enough to launch a new offensive from the southwest. This time it was led by King Edward III's eldest son, called Edward the Black Prince because of the black armor he wore. At Poitiers in 1356, the French showed they did not really learn anything from Crécy. They noted that England's infantry won Crécy, so the French knights dismounted before the battle began; this gave the English longbowmen more time to put arrows into their targets. The Black Prince won a victory as complete as his father's at Crécy; he captured France's King John II, brought him back to London, and held him for ransom, but France could not pay it. Four years later the English got the treaty they wanted, with King Edward renouncing his claim to the French throne in return for France's formal surrender of Aquitaine. John II was allowed to become king of France again, on condition that he would try as hard as he could to raise the ransom.

While the king was gone, the pent-up wrath of the lower classes exploded. The Dauphin (crown prince) of France had to flee Paris after a mob forced him to wear a red and blue cap, the colors of the rebel movement. The entire northern part of the country was engulfed in a peasant revolt called the Jacquerie, named after a peasant named Jacques who launched the uprising because the local lord had failed to protect his peasants from the war's destruction and mercenaries, while continuing to insist on his usual rents and services. Maybe the peasantry had a legitimate grievance, but their rebellion was doomed to fail because of a lack of planning and arms. The rebels set fire to manor houses and killed any lord they caught unguarded, but staves and scythes are no match for swords and lances. Brutal reprisals followed the crushing of the insurrection, known troublemakers were hanged outside their own cottages, and entire villages were razed.

The anarchy caused by the Jacquerie allowed a pretender to appear. When the rest of Europe heard about John II's capture, a merchant in Siena, Giannino di Guccio Baglioni, announced that he was he was the rightful king of France, John I. According to his story, it was not John the infant king that died forty years earlier, but the baby in the cot next to him; to keep John safe, the babies were switched and the living one was smuggled to Italy. Now Giannino announced his own claim to the French throne, though the only evidence he had for it was the fact that he was born at the same time as the real John. He got financial backing from a Jewish merchant in Venice, and after a fruitless trip to Hungary, he produced fake letters claiming that the Hungarian king backed him, too. Next he went to Avignon, but Pope Innocent VI wanted nothing to do with this business. The 1360 treaty between England and France left enough mercenaries unemployed for Giannino to recruit them as a small private army, but with King John II back, the opportunity to replace him had also passed. Instead of marching on Paris, Giannino was captured in Provence, and died in the pope's prison less than a year later.

Once the Jacquerie was over and the pretender was locked up, the French were able to renew the war, and this time they were on the winning side. In 1364 the same Dauphin who had been mocked by the Paris mob, now known as Charles V (Charles the Wise), became the next king of France. To lead the war effort he found a brilliant general from Brittany, Bertrand du Guesclin. Charles got Bertrand as a result of the Breton War of Succession (1341-64), an on-and-off conflict over who would be the duke of Brittany. Here the French supported one candidate and the English backed the other, so the war became a side show to the main conflict in the rest of France. Bertrand distinguished himself by ably leading the army of the French candidate, Charles of Blois, until Charles was killed. The pro-English winner, John V, then did an abrupt turn-around and announced he would be the vassal of the king of France, not the king of England. As for Bertrand, he was captured in the same battle that killed his lord, and he was ransomed by King Charles for 100,000 francs.

However, Bertrand du Guesclin's first campaign in the service of the king was on the far side of the Pyrenees. A civil war had broken out in the Spanish kingdom of Castile, between King Pedro the Cruel and his half-brother, Enrique of Trastamara. Bertrand convinced the leaders of the mercenaries running around in France that if they went with him on an expedition to support Enrique in Spain, they would win a greater profit than whatever they got from plundering peasants at home. The army of the kingdom of Aragon also joined them, and together the Franco-Aragonese-Castilian force ousted Pedro and installed Enrique on the Castilian throne. But it wasn't going to be a simple walkover for the coalition; Pedro escaped to Aquitaine and petitioned the Black Prince to come to the rescue. The showdown between the Black Prince and Bertrand came near the Castilian town of Najera, in April 1367, and again the English longbow won the day. English archers routed the Castilian cavalry; Bertrand's mercenaries were tougher, but without the cavalry they were eventually defeated. This time it was Enrique's turn to flee to France, and Bertrand was captured again. The Black Prince allowed Bertrand to go free, after Charles V paid another ransom; the French king felt he could not do without his best general. Pedro was reinstated, but soon afterward, he refused to pay the English the amount they were expecting, so they went home. No doubt they considered the Castilian civil war a disaster; four fifths of the English soldiers died on the campaign. When Enrique returned to Spain in 1369, Pedro had to fight him without allies. Pedro was murdered by Enrique after the battle of Montiel, and Castile was a solid ally of the French for the rest of the Hundred Years War.

In 1369 the people of Aquitaine, oppressed by the rule of the Black Prince, called on Charles for help, and he was happy to oblige. During the next ten years Bertrand wore down the English and drove them from all of the territory they held in France except for the ports of Calais, Cherbourg, Brest, Bordeaux and Bayonne. The secret behind his success was that he deliberately avoided battles with the English; whenever he heard where the English were, he sent his troops to take an unguarded castle somewhere else. He may have gotten away with this because he was a commoner; other French military commanders, having been brought up with the ideals of chivalry, attacked any enemy they could find and lost their battles, again and again.

Unfortunately Charles V profited little from Bertrand's victories; he felt compelled to give much of the recovered land to his brothers as extensive duchies. Once of those duchies, Burgundy, was an independent state, for all practical purposes. The next French king, Charles VI (1380-1422), was a witless youth who suffered from frequent, recurring spells of madness. Since nobody made it clear who would run the country while the king was in "his malady," two factions fought for the job: one was headed by the duke of Orléans and the count of Armagnac, while the duke of Burgundy led the other. This delighted the English; the two things they liked the most were chaos across the Channel and dead Frenchmen across the Channel.

Charles VI, also called Charles the Mad.

The military reverses brought forth the same spirit of rebellion in England that had triggered the Jacquerie in France. The Black Death had caused a critical shortage of labor, so those workers left alive felt important enough to demand higher wages; if they didn't get them, they deserted to new employers willing to pay their price. Parliament, composed largely of landholders, was so horrified that in 1351 it passed a law ordering imprisonment for any laborer who refused to work at pre-plague wages. But you can't legislate economics, and laws like these had little effect. Now it was England's turn to loathe the war and watch the common people challenge the government at home.

Edward III was a very popular king, even in his own family; while he was in charge there was peace at home. His fifty-year-long reign ended with his death in 1377. Edward the Black Prince had died a year earlier, so the Black Prince's ten-year-old son was crowned Richard II, and guided by a twelve-man council until he came of age. The most important advisor was John of Gaunt, the king's uncle, duke of Lancaster, and the richest man in England. To finance the war, Parliament imposed a new head tax, which anyone but a certified pauper was required to pay.

For the lower classes, this tax was the last straw. Open revolt flared in 1381, and rebel armies recruited the unemployed soldiers who had just returned from France. Led by an ex-soldier named Wat Tyler, the rebels marched from Kent and Essex to London. Sympathetic Londoners opened the gates for the newcomers, who promptly went on an orgy of destruction. During the next three days they murdered the Archbishop of Canterbury and burned many mansions, including that of John of Gaunt. At this point the country was on the verge of becoming a socialist state--in the fourteenth century! King Richard went to meet with the rebel leaders and agreed to their demands, which included an abolition of serfdom along with lower rents and taxes. But at a second meeting the following day, one of the king's followers slew Wat Tyler, and without a successor or an official ideology, the rebellion collapsed. As in France, the rebels went home with their demands unfulfilled and the prospect of retribution from the local lords.

Though Wat Tyler's revolt was a failure, the king got the message. The hated tax was eliminated, and serfdom began to die out. More important, the peasant and the townsman found they could work together to win more rights from the government. Never again in England would anyone allow an economic gap between the upper and lower classes to grow as great as it did in other countries. This also was the time when England produced one of the first known populists, a clergyman named John Ball. The nobility called him mad, but the common people listened as he fervently argued that those at the top of the social ladder were really no better than the masses they ruled over and profited from. John Ball's preaching was soon condensed to an easily remembered rhyme: "When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman?"

Though the rhetoric of the rebels sounds like the jargon coined by revolutionaries in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, this wasn't a true forerunner of the socialist/communist movements of our own time. The kind of government the rebels wanted to see was an absolute monarchy, because they felt if the king held all the power, he wouldn't tax them as much as the barons had. King Richard got along with the rebels, after all. The rebels also felt the king would not wage as many wars; Richard wasn't interested in fighting the French, anyway. More centuries would go by before revolutionaries got the idea that they could run a nation with no king at all (see Chapter 11).

A year after the Wat Tyler rebellion, Richard II married Anne of Bohemia, daughter of the Holy Roman emperor Charles IV, and began to assert himself against the great nobles who controlled Parliament and prevented him from acting independently. It took until 1389, and the help of his political friends ("The Lords Appellant"), but once he was in charge, Richard proved to be mentally unstable, cruel, and power-hungry. In 1394 he led 10,000 soldiers to Ireland, trying to reestablish his lapsed authority there (he was the first English king to visit Ireland in nearly two hundred years), and while away, his queen died. Two years later Richard got a peace treaty with France by marrying a French princess, Isabella. Though Isabella was only six years old, she came with 800,000 francs and a nice sized tract of land. That and a new circle of friends allowed him to turn against his old friends, who had kept him from ruling as an absolute monarch.

Among those he exiled was Henry Bolingbroke, his cousin and the son of John of Gaunt. In 1399 John of Gaunt died, and Richard confiscated Henry's inheritance, something he had promised not to do previously. Henry raised an army in revolt, returned to England while Richard was on a second military expedition to Ireland, and when the king came back, Henry captured him in Wales and forced him to abdicate (September 30, 1399). One day later Parliament ratified the abdication, and Henry took the crown as Henry IV. Richard II was imprisoned in Pontefract Castle, and his death in 1400 brought the 246-year-old Plantagenet dynasty to an end.

Since we have a new dynasty taking over here, not everybody could accept Henry IV as king. In fact, there was someone with a better claim to the throne: Edmund Mortimer, the 5th Earl of March and a great-great-grandson of Edward III. Edmund's family and the Welsh rebel leader, Owen Glendower, tried to oust Henry and replace him with Edmund, but Edmund was just a kid, so Henry nipped the revolt in the bud, and had Edmund and his younger brother Roger kept under house arrest at Pevensey Castle for the rest of his reign. Thus, when Henry died in 1413, his son had no trouble succeeding him as Henry V.

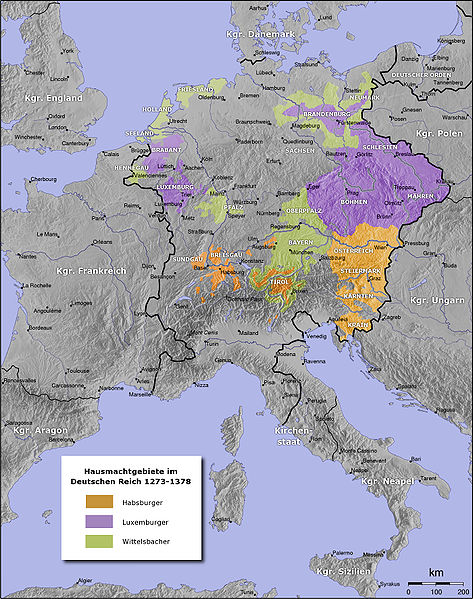

The Rise of the Hapsburgs

For nineteen years after the extinction of the Hohenstauffens, there was no Holy Roman emperor (1254-73). The pope did not recognize anyone who campaigned for the throne, which left the Empire without a central government. Lawlessness increased, and nobles waged petty feudal wars among themselves. During this time the most powerful noble was the king of Bohemia, Ottokar II; he used the "Great Interregnum" to build for himself an empire within the Empire, consisting of Bohemia & Moravia (today's Czech Republic), Austria and Slovenia.

The anarchy in the Empire persuaded the pope and the princes to end the Great Interregnum with a new imperial election in 1273. Ottokar ran for the top job, but the electors instead voted for a minor Swabian prince, Rudolf of Hapsburg, whom they believed would be no threat to their power and independence. This marked the beginning of the Hapsburg dynasty's long fortune, which would last for more than six hundred years.

At first all Rudolf had to his name was a castle in northern Switzerland. Ottokar paid homage to him, but refused to give back the lands he had seized previously. The pope placed Bohemia under the Papal ban, until Ottokar was killed in the battle of Marchfeld (1278). Bohemia and Moravia remained in the hands of Ottokar's son, Wenceslas II, but Rudolf succeeded in claiming Austria and Slovenia for the Hapsburgs, enlarging his personal estate tremendously. After Rudolf I, the Habsburgs moved their seat of power to Austria and promoted it to an archduchy, which made the Hapsburg family equal to the noble families who had originally elected Rudolf because of his insignificance.

Under the Hohenstaufens the Holy Roman Empire failed as an empire; under the Hapsburgs it failed as a purely German state. In 1278 Rudolf signed a treaty which recognized the Papal State as completely independent, ending the old power struggle between emperors and popes. He didn't even try to govern most of Germany, let alone Italy. The next emperor, Adolf of Nassau (1291-98), was not a Hapsburg, and less successful. He was deposed and killed in the battle of Gollheim by Rudolf's son, Albrecht I, who in turn ruled as emperor for the next ten years (1298-1308).

When imperial elections took place again, the electors passed over the Hapsburgs and chose Henry of Luxemburg, a French vassal and brother of the Archbishop of Trier. Henry VII (1308-13), like Rudolf I, concentrated his attention on feathering the family nest. He succeeded in landing Bohemia by marrying his son John to Elisabeth, the daughter of Wenceslas II. Because Bohemia had Europe's largest deposits of gold and silver, it was much more desirable than Henry's original estate, the county of Luxembourg. This self-interest is a little alarming, but as we saw previously, attempts by the emperors to buy the favor of their peers with gifts of land never really worked, so now it seemed more sensible to let the ruling dynasty keep available tracts. In fact, one could argue that what was good for the Hapsburgs and the Luxemburgs was good for the whole Empire, because central Europe had enough weak states already.

After Henry most of the prince-electors wanted another Hapsburg, namely the duke of Austria, Frederick the Handsome. A minority, however, favored Louis the Bavarian, who came from the Wittelsbach family. Both Frederick and Louis claimed they won the imperial election of 1314, so a civil war broke out. At this time the Papacy itself was vacant, so no pope could decide the outcome; force of arms did the job. In 1322 Frederick was captured, and from prison he recognized his rival as emperor. Despite his apparent victory, Louis IV remained unpopular; Pope John XXII refused to acknowledge his right to govern, and Louis responded by saying he did not need any pope's approval, just that of a majority of nobles. Then Louis marched into Italy, captured Rome, and installed Nicholas V as an antipope (1327-28). Nicholas gave the emperor the Church-approved coronation he wanted, but then abandoned his illegal claim to the Papacy when the real pope excommunicated him from Avignon.

Louis IV was the last emperor who tried to rule Italy; after his campaign the Italian states found themselves on their own. In the course of the fourteenth century Milan grew to dominate the Lombardy plain; its main rival was Venice, not an emperor who lived north of the Alps. In the far south, Robert the Wise, king of Naples (1309-43), attempted to gain control over the whole peninsula, but he mainly succeeded in weakening his own kingdom; the dynasty of Anjou went into decline afterwards. The Empire also lost ground to a slow French advance. Bit by bit, France nibbled at the lands between the Rhone River and the southern Alps, including Lyons. In 1349 France purchased a district called Dauphine, and this became the personal domain of the crown prince; this was where the French got the title Dauphin for their heirs. All this had previously belonged to Burgundy; the rest of Burgundy was ceded to France in 1378. Avignon was surrounded, but this was the time when it was the Church's headquarters, so it joined the Papal State instead.

To prevent church-state conflicts in the future, the imperial electors decided in 1338 that henceforth the candidate receiving the majority of votes would be both king of the Germans and Holy Roman emperor, without any need for confirmation from the pope. Louis IV viewed this as another attempt to limit his power, so he tried unsuccessfully to negotiate with both the princes and the pope. Instead, Pope Clement VI sponsored Charles of Moravia, the Luxemburg king of Bohemia, as an imperial candidate, thinking he would be easy to control. Thus Charles was elected next when Louis died in 1347.(11)

Despite Clement's hopes that Charles would reverse the electors' decision, the emperor diplomatically evaded the question of the papal role in imperial elections. In the Golden Bull of 1356, Charles put forth the rules for elections in writing, making the whole process more formal than it had been before. Charles limited the number of electors to seven, and specified that the electors would be three archbishops (of Mainz, Trier, and Cologne), the count Palatine of the Rhine, the duke of Saxony, the margrave of Brandenburg, and the king of Bohemia. Bavaria lost its vote, so it was always a second-rate member of the Empire after this, while the seven states containing electors became the strongest of all. Brandenburg and Saxony did particularly well; neither state had been important previously, but from this time onward they would be key players in German politics.

Like the other emperors at this time, Charles was most successful at enriching his personal domain. His base of power, Prague, was enlarged by many building projects, which included the first German university. The family realm grew in size, too; he acquired the Upper Palatinate in 1353, Lusatia and Silesia by 1368, and bought Brandenburg in 1373.(12)

The Luxemburg family fortunes reached their peak under Charles' son Sigismund (1378-1437). Sigismund got a lucky break early in his reign because the Hungarian king, Louis the Great, had no son. Mary, the eldest daughter of Louis, married Sigismund in 1385, bringing Hungary with her. However, the Hungarian dowry included a new enemy--the Ottoman Turks had recently invaded the Balkans, and were now subjugating Bulgaria, Serbia and Bosnia. King Sigismund, determined to stop the Turks at once, persuaded the pope to call for a crusade. As a result, he had a sizeable Franco-Hungarian force when he advanced down the Danube in 1396. Going on a crusade had never been this easy--Sigismund only had to cross his frontier to find infidels--but the leadership of it was no better than it had been in the past. They had the Bulgarian city of Nicopolis under siege when Bayezid, the Turkish sultan, arrived with his army. The French knights insisted on mounting a frontal charge against the Turkish position, for anything else would be less than chivalrous. They had done the same thing at Crécy, and here it got the same results; the Turks ambushed and annihilated the French. The Hungarians couldn't win on their own, so the last crusade was over almost as soon as it had begun. All it did was create an impression that the Ottoman Turks were unbeatable, which lasted until the late sixteenth century.

Sigismund had quite a collection of crowns: king of Bohemia, king of Hungary, king of Germany, and finally Holy Roman Emperor (the last was gained in 1410). This looked impressive on paper, but the more titles he had the less efficient he became. This especially was the case when he got involved in religious affairs. Sigismund successfully forced Pope John XXIII to convene the Council of Constance, which, as we shall see below, ended the Great Schism, but also made a martyr of the popular Czech preacher and religious reformer, John Huss, provoking a blazing revolt. Finally in 1436, the year before his death, Sigismund was able to reach an agreement that allowed him to enter Prague and mount the Czech throne, but for twenty years Bohemia, which should have been a useful home base, brought him nothing but humiliation.

Sigismund had no son, so his death ended the game for the Luxemburgs. His daughter Elisabeth married the next emperor, Albrecht II (1437-39). Thus the imperial crown returned to the Hapsburgs, this time permanently, and the Hapsburgs gained most of the lands that had belonged to their rivals: Bohemia, Moravia, Lusatia, Silesia and Hungary. However, the Luxemburgs managed to retain Luxembourg for a few more years, and Sigismund had passed Brandenburg to one of his vassals, Burgrave Frederick I of Nuremberg, in 1415. Frederick was from the Hohenzollern family, so this marked the beginning of another great dynasty, one which would play a pivotal role in the politics of the eighteenth, nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Unfortunately for the Hapsburgs, the natives of their new territories were non-Germans who didn't care much for German rule. They were also elective monarchies, like the Holy Roman Empire, so they voted the Hapsburgs out at the next opportunity. This happened in 1457 when Ladislas, the Hapsburg king of Hungary and Bohemia, died suddenly, and his uncle Frederick III (the current Holy Roman emperor) tried to take his place. Instead the Hungarians elected one of their own nobles, Matthias Corvinus; the Bohemians also chose a native, and when their first choice died, they offered the throne to the crown prince of Poland. The result was a three-cornered war between Hapsburgs, Hungarians and Poles; the Hungarians came out on top, taking Lusatia, Silesia and Moravia from the Bohemian-Polish coalition. In 1485 Matthias Corvinus even grabbed eastern Austria, and he made Vienna his capital for the next five years. Thus, Hapsburg family fortunes were at a low ebb when Maximilian I ascended the throne in 1493.

The Birth of Switzerland

This is a good place to cover how Switzerland got started. Though Switzerland is right in the middle of Europe, not much had happened there before the thirteenth century. It is easy to understand why; the land is poor in resources, except for edelweiss and yodelers, and because the Alps are such a formidable barrier, only somebody like Hannibal would want to go through the country, rather than around it. Anyway, we saw in the previous section that the Hapsburgs originally came from the Swiss Alps. The inhabitants around Lake Lucerne were always threatened by the Hapsburg ancestral castle looking over them, so in 1291 the cantons (communities) of Uri, Schwyz and Unterwalden formed an "Everlasting League," an alliance to keep them free from everybody else.

Unlike most European countries, Switzerland was founded by ordinary people, rather than by a king, and they did not crown anyone after they succeeded. You may have heard of one Swiss founding father, William Tell. According to the legend the Swiss all know, William Tell was a strong mountain climber and an expert crossbowman. One day the Hapsburgs sent an official named Albrecht Gessler to Uri. In Uri's central square, Gessler put his hat on a pole, and ordered everyone in the town to bow before the hat. When William Tell and his son Walter came to town and walked past the hat, Tell refused to bow to it; Gessler didn't see this as a friendly overture, and had Tell arrested. But Gessler had also heard of Tell's marksmanship, and wanted to see a demonstration, so he came up with a punishment that was both unique and cruel. If Tell could shoot an apple off the head of his son at 120 paces, he would be free to go; if he failed, Gessler would execute both Tell and his son.

Tell accepted the challenge, took two crossbow bolts (arrows) from his quiver, and successfully hit the apple with one shot. When Gessler asked why he had grabbed two bolts, Tell replied that if he had killed his son with the first one, he would have shot the second one at Gessler himself. Furious, Gessler ordered that Tell be taken to his castle dungeon. They boarded a ship to cross Lake Lucerne, but a storm struck in the middle of the crossing; Tell escaped and when Gessler pursued him on the lake's shore, Tell killed him with the second crossbow bolt. These events inspired the people of Uri to rise up and liberate their canton.

The problem with the William Tell story is that we can't prove any of it is true; William Tell may not have even existed. First, there is an historical error. The Swiss claim the apple-shooting incident took place on November 18, 1307, but as we saw above, Uri had been free of the Hapsburgs since 1291. Second, the oldest version of the story we have was written in 1474, more than a century after it supposedly happened. Still, the Swiss have made it a central part of their culture, to the point that in a recent survey, 60 percent of the Swiss polled said they believed William Tell was real, and the crossbow is one of Switzerland's national symbols because of him.

Now let's get back to what we know really happened. The Swiss have a reputation for being the most efficient people in Europe; it seems that they do everything right the first time they try it. That may have started with the Everlasting League, because the alliance worked superbly. Then came the task of raising a force to defend the League. Since horses were expensive, as we noted before, and the Alps are not a suitable place for cavalry, the Swiss concentrated on developing an excellent infantry, the famous Swiss pikemen. The pikemen showed what they could do in 1315, when 1,500 of them ambushed an attacking Hapsburg force that was ten times larger, and strung out along an icy road beside Lake Aegeri (the battle of Morgarten). In 1339 the three cantons, allied with Berne, defeated the Burgundians in the next major battle, at Laupen, and that allowed the League to live in peace for nearly fifty years. By 1353 five more cantons (Lucerne, Zurich, Glarus, Zug and Berne) had joined the original three, forming a confederation large enough to stand on its own. In 1415 they even conquered the Aargau valley, capturing Castle Hapsburg in the process. After several more defeats, the major powers chose to leave the Swiss alone, partly because of their country's spectacularly rugged scenery, and partly because of the Swiss practice of giving arms and military training to civilians. Two hundred years after the Everlasting League was founded, an admiring Machiavelli called the Swiss "the best armed and the most free people in Europe." The last attempt to conquer Switzerland was a short and vicious effort by Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, called the Swabian War (1499); after it failed he had to recognize the Swiss Confederation, now containing thirteen members, as an independent republic within the Holy Roman Empire. Later on, the Treaty of Westphalia declared Switzerland a completely independent country (1648). By this time Switzerland no longer got involved in the politics of its neighbors, so it became the ultimate neutral nation, long before the Congress of Vienna (see Chapter 13) put it in writing.

The Union of Kalmar

The Hanseatic League grew so aggressive toward Scandinavia that it became a downright kingmaker. Denmark's King Waldemar IV (1340-75) fought the Hansa twice; the first conflict went in his favor (1361-63), but in the second the Germans beat him so badly that he was forced to grant trade concessions to the League, and the right for them to approve whoever became king of Denmark in the future. In 1375 Waldemar died, and his daughter Margaret took charge; she compelled everyone to accept the election of her five-year-old son Olaf as the next king. Naturally this meant that Margaret would rule as regent, "the mighty woman and keeper of the house." Nor was that all; Margaret's husband was King Haakon VI of Norway, and when he died in 1380, Margaret offered to make Olaf the Norwegian king, too. The Norwegians accepted, so Margaret of Scandinavia became the ruler of two countries.