| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

The Anglo-American Adventure

Chapter 3: Pioneer America, Part II

1783 to 1861 (USA), 1783 to 1867 (Canada)

This paper is divided into four parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| Unfinished Business With the Tories | |

| Canada Reaches the Pacific | |

| The American Cincinnatus | |

| The Articles of Confederation | |

| The Writing of the Constitution | |

| Ratification | |

| "First In the Hearts of His Countrymen" | |

| John Adams at the Helm | |

| Republicanism, Jeffersonian Style | |

| The Lewis & Clark and Pike Expeditions | |

| Aaron Burr Kills Hamilton |

Part II

Part III

| The End of the Beothuk | |

| Deep in the Heart of Texas | |

| Old Kinderhook, Tippecanoe, and Tyler Too | |

| The Canadian Rebellions of 1837 | |

| The Search for a Northwest Passage (revisited) | |

| Westward Ho! | |

| The Cheerful Forties | |

| "From the Halls of Montezuma" |

Part IV

| Mormons, Doughfaces, and the California Gold Rush | |

| The Free Soil Republicans | |

| A House Divided | |

| The Utah War and the Colorado Gold Rush | |

| Meanwhile, North of the 49th Parallel | |

| Early American Demographics |

The War of 1812

Preliminary Activities

Though Jefferson's presidency ended on a rather unhappy note, Americans were not upset enough to give the government back to the Federalists. Because he had contributed more than anyone else to the Constitution, one would expect James Madison to be the chief Federalist, and indeed he was--in the 1780s. More recently, however, he felt that the central government no longer acted like the limited government he envisioned, so he became a Democratic-Republican and worked with Jefferson most of the time. This made Madison the logical choice to become the next president after Jefferson, and he won by a landslide in 1808 (the best candidate the Federalists could find was Charles Pinckney, the same one they had nominated in 1804). He inherited a nation that was still expanding; pioneers were not only moving into recently acquired territories like Louisiana, but also into areas still labeled as belonging to Spain or the Indians. In 1810 a group of American settlers on the Gulf Coast proclaimed all the land between Pensacola and the Mississippi River the "Free and Independent Republic of West Florida," overpowered the Spanish garrison at Baton Rouge, and raised a blue flag with a single star on it. Before the year was over President Madison ordered the annexation of West Florida, declaring (incorrectly) that it had been included in the Louisiana Purchase. The land around Lake Pontchartrain that now makes up eastern Louisiana (the so-called "Florida Parishes") was occupied at once. Spain disputed the US claim, of course, and in 1813 Madison acted again, this time sending General James Wilkinson to annex the Mobile District; this would become the southernmost part of Alabama and Mississippi. Meanwhile the territory of the lower Mississippi valley was first organized as the Orleans Territory, and then in 1812 it became the state of Louisiana.

Before statehood came to Louisiana, it saw the worst slave revolt in American history (January 8-10, 1811); unlike the Nat Turner revolt, twenty years later, chances are you haven't heard of it. Today it is sometimes called the German Coast Uprising because in the eighteenth century, the French allowed quite a few German immigrants to settle the area where it took place (modern St. John the Baptist and St. Charles Parishes, LA). The local slaves included a mulatto from Haiti named Charles Deslondes, who knew from his homeland's experience what armed slaves can do, so while he behaved well enough to be appointed an overseer over other slaves, he also spent years plotting a revolution. When the slaves revolted, they quickly captured the plantation they were on, and then they made a surprisingly orderly march in the direction of New Orleans. As they moved along, they destroyed plantations and more slaves joined the rebels, until there were an estimated 250-500 of them. Whereas the slaves in the Nat Turner revolt only wanted to free themselves and kill their masters, the ultimate goal of these slaves was to establish a black republic in the Mississippi delta. Deslondes and his co-conspirators knew that if they were going to have their own country, they would need a proper army to defend it, so when they stole weapons from the plantations, they also stole militia uniforms, marching drums and flags, and issued them to the "troops."

Ahead of the slave parade fled terrified slave owners to warn New Orleans. On the second morning of the revolt, the New Orleans militia encountered the rebels on the plantation where they stopped for the night, and because the rebels ran out of ammunition first, they were easily overwhelmed. About 40 to 45 slaves were killed in the battle; the slaves in turn only killed two white planters in the whole rebellion. Charles Deslondes escaped but was soon captured by the militia; they chopped his hands off, shot him and burned him alive in a bundle of straw. In the aftermath, a few dozen slaves were beheaded or hanged, and the legislature of the Orleans Territory paid $300 to the slave owners in compensation for every slave killed or executed.

The most amazing part of the story is that Southern whites succeeded in covering up how bad the revolt really was. Some Louisiana newspapers downplayed it, calling the rebels mere bandits, while others did not mention it at all. The white refusal to admit that a well organized, politically sophisticated slave revolt could happen caused almost everyone to forget about it for the next two hundred years, until historians started drawing attention to it, on the bicentennial of the event in 2011. Today the only memorial to the revolt is a plaque marking the spot where it started.

To the northwest, the Indians had put together their largest alliance since that of Pontiac, nearly fifty years earlier. This time it was the work of two brothers from the Shawnee tribe: Tenskwatawa, better known as "the Prophet," and Tecumseh. Like Hiawatha and Deganawida, the legendary founders of the Iroquois Confederacy (see Chapter 2, footnote #4), these two provided both spiritual and secular leadership, enough for several tribes. A drunkard and ne'er-do-well in early life, Tenskwatawa woke up one morning, declared that his previous behavior had been wrong, and began to preach abstinence. This was the first of several visions the Prophet revealed; from 1805 onward, he led a religious movement which claimed the white man was descended from an evil great serpent, and taught that the Indians should reject all white customs, white-grown crops, white-made products, and have no more dealings with the whites. Tecumseh, on the other hand, was sober from the start, having a reputation as a great warrior because he had fought in the battle of Fallen Timbers. Their main opponent was the governor of the Indiana territory, William Henry Harrison, another veteran of the battle of Fallen Timbers; when he saw followers gathering around Tenskwatawa and Tecumseh, Harrison sent them an open letter, calling on the Prophet to perform a miracle like the prophets of Biblical times: "If he is really a prophet, ask him to cause the Sun to stand still or the Moon to alter its course, the rivers to cease to flow or the dead to rise from their graves." The two brothers met in private for an hour, and then the Prophet announced that fifty days from that time, the sun would suddenly be hidden in the middle of the day. Sure enough, a solar eclipse occurred on the predicted day (June 16, 1806), and many more Indians joined Tenskwatawa and Tecumseh when they saw it. It was never clear how the Prophet knew an eclipse was coming; the most popular theory is that because Tecumseh could read English, he must have seen the eclipse mentioned in an almanac, and told his brother that useful tidbit of information later. In 1808 the two brothers left their native Ohio, because other Shawnees didn't want them around anymore, and they set up a new home village near the junction of the Wabash and Tippecanoe Rivers in Indiana, appropriately named Prophetstown.

Tecumseh also spent a good deal of time persuading Indians to join his cause, but he did it in a more straightforward way. Like a politician on the campaign trail, he traveled widely, from Canada to Florida, and talked to as many Indians as possible. Back at home, members of the movement accused those Indians who signed treaties, or otherwise tried to cooperate with the United States, of practicing witchcraft, and even executed some in the resulting witch-hunt. When Harrison and several Indian leaders signed the Treaty of Fort Wayne in 1809, which sold two major tracts of Indian land to the United States, Tecumseh announced his opposition; he declared that because the land in question belonged to all tribes, it could not be sold without the consent of all tribes, and American citizens should not try to settle on it. Tecumseh and Harrison had a peaceful meeting at Vincennes in August 1811, but now it seems that neither one of them expected a peaceful resolution of the dispute; afterwards Tecumseh went south to recruit more allies,(27) while Harrison moved more than a thousand soldiers north, and built Fort Harrison near present-day Terre Haute. Then Harrison received orders from the Secretary of War, authorizing him to use force to disperse the Indians gathering around Prophetstown. Tenskwatawa sent out 500 warriors, in an effort to strike the Americans first. In the resulting conflict, the Battle of Tippecanoe, the Americans suffered more casualties, but held their ground, and the next day they went on to occupy and burn Prophetstown. The Prophet was disgraced as a leader, because he had predicted earlier that the weapons of Harrison's men could not hurt his warriors, while Harrison immediately became a hero, and was often called "Tippecanoe" after that. Tecumseh managed to keep the war going, though, and after the British in Canada agreed to give him aid, Tecumseh's War merged into the War of 1812 (which from the British point of view was an American front in the Napoleonic Wars).

The War of 1812 was the strangest war in US history; bad communications caused it, and were a factor in its ending. Over in Europe, the British had succeeded in keeping Napoleon contained, but they hadn't yet won any major land battles, so the French Empire was a long way from being crushed. American merchants needed access to both Great Britain and France in order to be successful in commerce, but whenever neutral American shipping approached either country, it ran the danger of being harassed by the other's navy. Earlier we talked about the British practice of impressing American crews to serve on Royal Navy ships, which bothered Americans the most. An aggressive faction of young congressmen emerged, led by Henry Clay of Kentucky and John Caldwell Calhoun of South Carolina. They called for an invasion of Canada, to punish the British for supporting the Indians in the west. President Madison agreed with the "War Hawks" that Canada could be easily conquered, while most of the British army and navy were busy with Napoleon. As tensions rose, he recommended that Congress declare war if Britain did not change its policies, especially impressment. Congress went ahead and passed a war declaration on June 18, 1812. What they didn't know was that just five days later, on the other side of the Atlantic, the British decided to stop harrassing American commerce, taking away the main reason for the war.

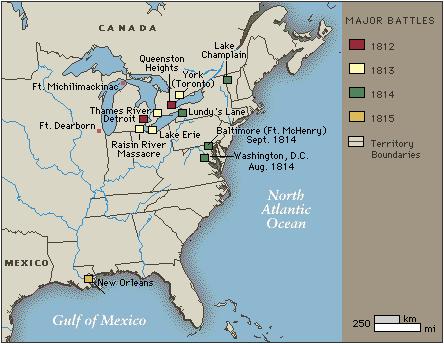

Important battles of the War of 1812.

Campaigns of 1812

There were three major fronts to the war: the Atlantic, the Great Lakes Region, and the South. On the sea, you would expect the British Navy to beat all challengers, but while British ships outnumbered American ships by four to one, the Americans had gained experience from fighting the Barbary pirates, so they gave as good as they got. The most celebrated victories were those of the USS Constitution, which captured two British frigates, the Guerriére and the Java; in the first battle, an American sailor saw a cannonball actually bounce off the Constitution's wooden hull, which led to a new nickname: "Old Ironsides." American privateers also did well, but much of the Atlantic coast eventually came under a British blockade. Finally, Jean Lafitte, the famous pirate captain, helped out the Americans by raiding non-American ships in the Gulf of Mexico; Andrew Jackson would use his crew at the battle of New Orleans to kill isolated groups of British soldiers, because they wore red shirts, fooling the British into thinking the pirates were on their side.

The "War Hawks" in Congress had spoken rashly about conquering Canada and turning it into another US territory to be settled. Henry Clay, for instance, once said that the Kentucky militia by itself could overrun Upper Canada and take Montreal in four weeks. However, the US army did not have the kind of veterans the navy had. At the beginning of the war, the army only had 7,000 men, and while Congress authorized enlarging the force to 35,000 before it declared war, these soldiers would be raw, green recruits for quite some time. The generals had seen service in the American Revolution, but none of them were inspiring leaders; there wasn't anybody like George Washington or Anthony Wayne in that group. The lack of experience and leadership showed in the Canada invasion.

Montreal and Quebec were still the two most important Canadian cities, so logically, the Americans would have their best chance of winning if they captured those cities first. Instead, the first battles were fought in the west. The British were able to take Mackinac Island easily, because the American garrison defending it didn't even know a war had begun, and were thus caught unprepared when a British cannon started bombarding them. That put Fort Detroit in a precarious situation, so in July General William Hull, the commander of the force defending Detroit, decided to protect it by going on the offensive, and crossed the border into Upper Canada. However his men were poorly equipped, insubordinate and unreliable, and when they heard that a force of 1,300 British soldiers, Canadian militiamen and Indians was coming, they quickly retreated.

Back in Michigan, 600 Indians, British soldiers and Canadian militiamen faced Detroit. This was a much smaller force than the defending garrison, but Tecumseh and the British commander, Isaac Brock, captured Detroit by pulling a series of tricks. First, knowing that Hull was terrified of "the savage Indians," Brock wrote a letter to his superiors, falsely claiming he would not need reinforcements because the 5,000 Indian warriors he already had were enough to take Detroit by themselves, and then he made sure the letter fell into American hands. Second, because the Americans weren't afraid of Canadians, Brock dressed the militiamen in red coats, to make them look just like the British regulars. Third, Tecumseh marched his men in circles, shouting war whoops and keeping the troops visible in a clearing between the trees as much as possible; as soon as each man was out of sight in the trees, he would run around the fort until he got back to the clearing again. This fooled the defenders into thinking there were thousands, not hundreds of Indians, outside the fort. Fourth, Brock warned Fort Detroit that he was "losing control" of Tecumseh, and if there was a battle, it would probably end with an Indian massacre. The psychological warfare worked. By the time the American force got back from Upper Canada, Hull was so frightened that he spent the whole afternoon sitting on the ground in a corner of the fort, drooling tobacco juice on his chin and vest. The next day (August 16), he surrendered his army and the fort without firing a shot. This was the only time after the American Revolution when a US city surrendered to a foreign power.

The day before Detroit fell, Fort Dearborn (modern Chicago) was abandoned, also under orders from Hull. 148 of that fort's occupants, soldiers plus their wives and children, began marching to Fort Wayne, but a mile and a half after they started, they were ambushed by Indians from the Potawatomi and Miami tribes. More than fifty Americans were killed in the resulting massacre, and the rest were sold to the British, but since the British didn't believe in this kind of slavery, they promptly released the "slaves" after buying them. Fort Dearborn was burned to the ground, the Americans effectively lost control of Michigan, and Ohio was now open to a British counter-invasion.

The Americans made a second attempt on Canada in October, this time from the other end of Lake Erie. A small force crossed the Niagara River and got as far as Queenston Heights, where it met defending British troops. The American commander, Stephen Van Rensselaer, ordered the New York militia to go in as reinforcements, but the militia would not budge, insisting that it could not legally be sent out of the United States (see footnote #3). Van Rensselaer could only watch while the British defeated and forced the surrender of the Americans, but Isaac Brock, the British general who had taken Detroit, was also killed in that battle, so it could have been a lot worse.

Van Rensselaer's replacement, Inspector General Alexander Smyth, was a total incompetent, whose main accomplishment in the army to this point was translating a set of French military guidelines. In November, Smyth ordered 2,000 men into boats to cross the Niagara River, and then ordered them out again. Three days later, he gave the same orders, and the soldiers mutinied, shooting at the general's tent. Smyth fled all the way to his home in Virginia, and Congress got him out of the army by abolishing his position; Madison's comment on the affair was that Smyth's "talent for military command was . . . equally mistaken by himself and by his friends."

A fourth attempt on Canada was tried in the east by General Henry Dearborn. It only got as far as Lake Champlain before the New York militia again refused to cross the border, turned around, and marched back into winter quarters at Plattsburgh, NY.

Campaigns of 1813

On the western front, William Henry Harrison took Hull's place, but his attempt to retake Detroit was halted at the battle of the River Raisin, in northwest Ohio (January 1813). He built Fort Meigs nearby to protect the remaining troops, and it successfully withstood two attacks by a joint British-Indian force, led by Colonel Henry Proctor and Tecumseh, the following May and July. A third British-Indian attack, at Fort Stephenson on the Sandusky River in August, was also held off, and the British gave up trying to conquer Ohio.

By the end of 1812, both sides realized that victory would go to the side that controlled the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River, so the winter of 1812-13 saw a race to build ships on Lakes Erie and Ontario. In April 1813, General Dearborn sent a raiding party across Lake Ontario, which managed to capture and burn York (modern Toronto), the capital of upper Canada. Zebulon Pike, the explorer of Colorado, was killed in that battle. However, the largest military base in Upper Canada was at Kingston, not York, and Dearborn felt he did not have enough troops to take Kingston, so he didn't try. A British counterstrike on Sackett's Harbor, NY failed, and the next three engagements on Lake Ontario, in the summer of 1813, were indecisive.

At the other end of Lake Ontario, an American amphibious force captured Fort George, the British fort guarding the Niagara River, and then advanced to Stoney Creek. Here 700 British ambushed 3,400 Americans, fought them to a draw, and captured both of the American commanders, John Chandler and William Winder, when they wandered over to the British line, mistaking those troops for their own. Unfortunately for the Americans, their incompetent generals were released, allowing them to receive new commands in 1814 (Chandler was put in charge of defending the coast of New Hampshire and Maine, and Winder got the task of defending Washington). Then naval support for the Americans ended, because their ships were withdrawn to defend Sackett's Harbor (see above). Before the army pulled out, they decided to protect their rear by taking out the nearest British outpost. However, Laura Secord, the wife of a British officer, overheard American officers discussing their plans, and went to warn the outpost, thereby becoming the "Canadian Paul Revere." The result, the battle of Beaver Dams, was an ambush of the Americans by the local Mohawks, followed by their surrender to a much smaller British and Indian force.

On Lake Erie, the Americans finished building their fleet of nine ships in September. The British squadron of six ships based at Amherstburg, just across the river from Detroit, sailed forth to meet the new fleet; that encounter was the Battle of Lake Erie (September 10, 1813). Although the American commander, Oliver Hazard Perry, had to abandon his flagship, that was the only American ship lost; the entire British squadron was captured. This prompted Perry to write a note to General Harrison, which contained one of the most famous quotes from an American officer: "We have met the enemy and they are ours." With the Americans now in control of the lake, the British felt overextended, and they abandoned Detroit; Harrison crossed the border in pursuit, capturing both Detroit and Amherstburg. He caught up with the British at the Thames River on October 5. The battle of the Thames saw the British routed, and Tecumseh was killed, breaking the Indians' ability to resist. A Kentucky colonel, Richard M. Johnson, claimed he fired the shot that brought down Tecumseh, and used that claim to promote a career in politics after the war, eventually becoming vice president in the 1830s (see footnote #44). As for Harrison, he now felt overextended, so after the battle he returned to Detroit and Amherstburg. Except for an American raid across the frontier that burned Newark (modern Niagara-on-the-Lake) in December, followed by a British raid that briefly captured Fort Niagara and burned Buffalo, NY, that was the last activity in Upper Canada for 1813.

In the last few paragraphs we covered the fighting in Upper Canada, but Lower Canada, where Montreal and Quebec are located, was not forgotten. Late in 1813, a plan was finally agreed upon for invading Lower Canada. General James Wilkinson would transport 7,000 troops on ships from Sackett's Harbor, sailing down the St. Lawrence, where they would join 4,000 troops marching up from Lake Champlain, led by General Wade Hampton, and together they would go after Montreal. The plan probably would have worked at a different time, under different commanders. But because the two forces didn't start moving until October, bad weather hindered Wilkinson, while bad roads likewise slowed down Hampton. Worse, Hampton disliked Wilkinson and refused to cooperate with him, which led to poor morale all around. This allowed much smaller British units to intercept both forces before they united. At the battle of Crysler's Farm, Wilkinson was defeated by a British force only one-tenth the size of his own. Meanwhile at Châteauguay, Canadian buglers tricked Hampton into thinking the number of Redcoats ahead was much larger than it actually was, so he turned around as well. As the two generals withdrew from Canada, it seemed that they had been less interested in winning than in blaming each other for the failure of the expedition.

The Creek War

Meanwhile to the south, a second conflict was beginning, because Tecumseh's Creek allies were finally ready. As John Sugden put it:

"We speak of the War of 1812, but in truth there were two wars. The War between the Americans and the British ended with the treaty of Ghent. The war between the Big Knives [American frontiersmen] and the Indians began at Tippecanoe, and arguably did not run its course until the last Red Sticks were defeated in the Florida swamps in 1818."(28)

The southern conflict, also known as the Creek War, began in early 1813, when the "Red Stick" tribes of Creeks (see footnote #27) attacked those tribes which had tried to adopt elements of Western civilization like domesticated animals, modern farming techniques, and spinning wheels. The only thing made by the white man that the Red Sticks did not destroy were guns and steel knives, which they kept for themselves, as you might expect. American soldiers got involved when they intercepted a party of Red Sticks in Alabama, who were returning from a trip to buy ammunition from the Spanish governor of Pensacola, Florida. This resulted in the Americans ambushing and scattering the Indians, followed by an Indian counter-ambush when the Americans started looting the pack horses of the Red Sticks (the battle of Burnt Corn, July 27, 1813). One month later the Red Sticks attacked Fort Mims, massacring 400-500 American militiamen, settlers, and pro-American Creeks; only the black slaves of the Americans were spared, and they now became slaves of the Red Sticks.

Alarmed by news of the massacre, the states of Tennessee and Georgia mobilized their militias; so did the Cherokee, who were rivals of the Creek and had a grudge against the British dating back to the French and Indian War. Tennessee's militia of 5,000 men, which included 200 Cherokee, was divided into two equal parts: the eastern unit under General William Cocke, and the western unit under Colonel Andrew Jackson. The trip southward was greatly slowed by a lack of supplies and a lack of discipline; most of the men had signed up for short terms of service, and wanted to go home when those terms expired. Jackson ended up dismissing many before they deserted outright, so that by the end of 1813 he was down to 103 men, before reinforcements arrived. After the two forces united, a full-scale mutiny broke out among the eastern Tennessee men, once they learned that Jackson's men had only enlisted for three months, compared with six months for them. Jackson accused Cocke of starting the mutiny and had him arrested (he was later acquitted); he commanded the whole Tennessee militia after that.

By that time, Jackson's admiring soldiers were calling him "tough as old hickory," giving him the nickname that has been used for him ever since. In the east, Georgia contributed 950 militiamen and 300-400 friendly Creeks, but when they were attacked at Calibee Creek (January 29, 1814), they pulled back into Georgia, so they never joined Jackson's force. The decisive battle came at Horseshoe Bend, in eastern Alabama, where Jackson trapped and killed 800 Creek, with a ferocity that shocked many on both sides (March 27). In August Jackson ended the Creek War by forcing the Creek to sign the Treaty of Fort Jackson, which called on the Creek to give up 23 million acres of land (southwest Georgia and half of Alabama). At this point Jackson saw no difference between those communities that were for him and those that were against him, so land was taken from both. Even the Cherokee felt like losers, because they believed some of the surrendered Creek land really belonged to them.

Campaigns of 1814

1814 saw the collapse of Napoleon's empire in Europe, allowing Britain to move some of its better units to North America. This meant that the opportunity for the United States to mount a successful invasion of Canada was over. However, this did not rule out an offensive strategy, because the end of the war was now in sight, and if the Americans were in a position of strength when the fighting stopped, they would get a peace treaty written in their favor. The US army in the north was larger, more competent, and led by a new generation of generals: Jacob Brown and Winfield Scott on the Niagara frontier, and George Izard on Lake Champlain. In mid-1814 the first two generals were ready for a new campaign; Brown quickly captured Fort Erie, while Scott intercepted the British force when it showed up. The battle of Chippewa (July 5) was an astonishing victory that showed how much the American troops and their leadership had improved; it caused the British general, Sir Phineas Riall, to exclaim, "These are regulars, by God!" Later on the historian Henry Adams had this to say about the battle: "Small as the affair was, and unimportant in military results, it gave to the United States Army a character and pride it had never before possessed."(29) Brown advanced to Queenston, and then fell back when British reinforcements arrived. The two sides stood their ground at Lundy's Lane (July 25), which turned out to be the bloodiest Canadian battle of the war. Casualties were roughly even, so the battle was declared a draw: 878 British vs. 860 Americans lost, Brown and Scott were seriously wounded, Riall was wounded and captured, and even Riall's replacement, Lieutenant Governor Gordon Drummond, suffered a neck wound. As a result, the Americans retreated to Fort Erie, and the British to Queenston. After that Drummond put Fort Erie under siege in August, but it held out until the Americans evacuated and destroyed the fort in November.(30) Meanwhile in the west, a British expedition from Mackinac Island captured Prairie du Chien, a trading post in Wisconsin, on July 20, and because the Indians in the neighborhood were on their side, they managed to hold it for the rest of the war, beating off an attempt by Major Zachary Taylor to recover it.

On the New York-Lower Canada frontier, it was the British who were trying to finish the war with a good offensive. They had 15,000 men based in Montreal, 11,000 of them veterans, and they decided to try the same strategy that had been attempted twice during the American Revolution: strike south into New York, using Lake Champlain and the Hudson River as their path to follow. To avoid a disaster like the battle of Saratoga, they built a squadron of ships, for the purpose of gaining control over Lake Champlain. The American naval commander, Captain Thomas Macdonough, knew he would be at a disadvantage, especially if the British squadron caught his ships in open water, so he had them drop anchor at the entrance to Plattsburgh Bay. Sure enough, the British squadron, commanded by Captain George Downie, arrived at Plattsburgh Bay on September 11, 1814. Nearby was the British army, commanded by Sir George Prevost, and it would try attacking Plattsburgh by land while Downie attacked from the lake. Downie's flagship, the Confiance, had 36 guns, and after two hours of fighting, it managed to silence all the exposed guns on Macdonough's flagship, the 26-gun Saratoga. Then Macdonough pulled a trick that turned the battle in his favor: he used lines attached to his anchor cables to turn the Saratoga around, bringing to bear the guns on the other (port) side, which so far had not been used or damaged. Captain Downie was killed by the surprise salvo, and the Confiance pulled out of range, leaving the other British ships to surrender. Prevost broke off his own operation when he heard what happened on the lake, and immediately retreated back to Canada; he wasn't about to march through the wilderness without a supply line. Nearly a century later, Theodore Roosevelt would call the battle of Lake Champlain the most important naval battle of the war.

The United States never tried to invade the Maritime Provinces of Canada because the nearest states, those of New England, were against the war, and thus untrustworthy. In fact, Nova Scotia made a profit off the war because New England didn't; Nova Scotian ships went on privateering expeditions, capturing American vessels and confiscating their cargoes. On the mainland, while the British were being turned back from Plattsburgh, another British force invaded eastern Maine from New Brunswick, and captured the towns of Castine, Hampden, Bangor and Machias (August-September 1814). Since the border of Maine had not been settled by the previous war, the British had hopes they would keep this area; it would shorten communications between Lower Canada and Nova Scotia. US citizens living there were given the choice of swearing allegiance to the king or leaving; most swore allegiance and were even permitted to keep their guns. In Canada itself, reinforcements continued to arrive from Europe. In December 1814 a British ship, the HMS Newcastle, attacked Cape Cod, Massachusetts, and marines came ashore at Rock Harbor; they were thrown back by the local militia, with the British suffering one fatality. The British blockade of the Atlantic coast has also gotten more effective, nearly bankrupting the US government; only loans from two foreign-born philanthropists, Stephen Girard and John Jacob Astor, allowed it to keep going until the war ended. By the winter of 1814-15 there were more than 20,000 British troops in Canada, and they probably would have been used for an all-out invasion of New York and New England that spring, if peace hadn't broken out first.

The end of the war in Europe meant that Britain had more ships available, as well as more men. This allowed them to try something new, an invasion of Chesapeake Bay. The US Navy had been expecting this when a British blockade of the area was set up in 1813, and built twenty barges to defend Chesapeake Bay, but this didn't even slow the British down when their fleet entered the bay on August 19, 1814. The American troops defending Washington were mostly inexperienced militiamen, and they were scared away so quickly that only eight of them were killed in battle (August 24). At first President Madison borrowed a pair of dueling pistols from the Secretary of the Treasury and rushed to the battle in a carriage, but when he saw what was happening, he turned around and fled to Virginia. After that nothing kept the British from marching into Washington and burning the Capitol, the White House, the Treasury and the navy yard. The first lady, Dolley Madison, stayed long enough to rescue some valuables (the White House silver plate, a painting of George Washington by Gilbert Stuart, a wagonload of official papers and her pet parrot), before joining her husband; then the Executive Mansion was torched.(31) However, the British didn't stay to occupy the city, but moved on to Baltimore when they were done destroying it, allowing the president to return four days later.

Baltimore, unlike Washington, put up a stiff resistance (September 13). When the British failed to take Fort McHenry, which guarded the entrance to Baltimore Harbor, the only thing left for them to do was call off the campaign. That battle is noteworthy because Francis Scott Key, an American lawyer held prisoner on one of the British ships, watched it, and was inspired by how the American flag still flew over the fort after the bombardment. Afterwards he wrote a poem about it that later became the national anthem, "The Star-Spangled Banner."

The Battle of New Orleans

Despite this setback, the British felt that time was on their side. After leaving Chesapeake Bay, the fleet went to the Caribbean, where it was joined by transports carrying 12,000 men, all veterans of the Napoleonic Wars, led by General Sir Edward Pakenham. This time the plan was to invade the United States from the south, starting with the capture of the port of New Orleans. Up to this point, only the US and France had recognized the Louisiana Purchase, and Napoleon was in no position to get involved (he was exiled to Elba by now), so there was a chance the British could conquer the whole West if New Orleans fell. On the American side, the nearest available force was that of Andrew Jackson. Since we last saw Jackson, he had invaded Florida and captured Pensacola, without the federal government's permission, because he correctly guessed that Spain was helping the enemy. Now that New Orleans was threatened, Jackson was ordered to get out of Florida and prepare to defend the mouth of the Mississippi. The first British troops landed on the coast in mid-December, and Jackson attacked immediately; this skirmish was intended not to throw the British back into the sea, but to give the Americans more time to get their artillery into position. It was bloody enough to make Pakenham wait until his whole force arrived. When he finally moved on New Orleans, on January 8, 1815, he had 8,000 men, including some of the best in the British army, compared with 5,000, mostly Kentucky and Tennessee militiamen, under Jackson's command. The British advanced under heavy fog, but around the time they got close to the defenses, the fog suddenly lifted. Now Jackson showed that the time he had gained for placing American guns paid off, as the British were mowed down by muskets and grapeshot. In 25 minutes, the British suffered nearly 2,000 casualties: 385 killed, 1,186 wounded and 484 captured; the dead included Pakenham himself. The American losses were trivial by comparison: 13 killed, 58 wounded, 30 captured. This was America's biggest victory of the war, and it made Jackson the war's most popular hero. For the next fifty years, January 8, the anniversary of the battle of New Orleans, was celebrated by Americans as a national holiday, second only to the Fourth of July; this is the only holiday the United States ever observed for a military victory.

The only problem with Jackson's victory was that the War of 1812 was already over. During the previous summer, President Madison had sent Albert Gallatin and John Quincy Adams (the son of former president John Adams), to Ghent, Belgium, to negotiate with the British. They signed a treaty ending the war on December 24, 1814, two weeks before the battle of New Orleans, but the news hadn't yet reached America. Pakenham had heard about the treaty, but was under orders to keep pressing ahead until it was ratified by Congress, which probably wouldn't have happened had he won at New Orleans. Thus, when the British forces pulled away from Louisiana, they looked for another target on the Gulf Coast, and took Fort Bowyer, at the entrance of Mobile Bay, on February 11. Then a copy of the treaty arrived in Washington to be ratified, and hostilities ceased.

The signing of the Treaty of Ghent. Admiral of the Fleet James Gambier (left) shakes hands with John Quincy Adams.

No territory changed hands as a result of the treaty of Ghent; all occupied land was returned to whoever had it before the war started. What the war did was confirm three things that should have been settled by the American Revolution: the United States was no longer part of the British Empire, Canada would not become part of the United States, and Maine would not become part of Canada. In that sense, you could call the War of 1812 the "Second War of Independence." Though the treaty declared the war a draw, each side felt it won, because it had taught the other side a lesson. The United States and the United Kingdom were like two tough guys who fight without winning until they wear themselves out, and then they become friends, now that they have mutual respect for one another; US-UK relations have been great for most of the years since the war ended. The Canadians came out of the war feeling good because they had turned back a US invasion; recently a US historian admitted that if anyone can be called a winner of the War of 1812, it is Canada. The residents of Maine resented how Massachusetts had failed to defend them (the last British troops did not get out of occupied Maine until 1818), and this started a movement to end the rule of Massachusetts over Maine.

In 2008, Canadian artist Douglas Coupland raised this monument to the War of 1812 in Toronto, showing a triumphant Canadian and a defeated American as toy soldiers. From Wikimedia Commons.

However, there was one other participant in the war who lost big-time: the Indians. Now that Tecumseh's alliance had been shattered, and the Creek tribes had been defeated, the door was wide open for American pioneers to settle both in the south and the west. Another Midwestern territory, Indiana, became a state in 1816, and construction had already begun on "The National Road," which would become the main highway for those going west.(32) Whereas the battles lost by the Americans and British were just setbacks, the Indians now found that everything they held east of the Mississippi River was in jeopardy.

Finally, the War of 1812 finished off the Federalist Party. Commerce-dependent New England strongly opposed it, calling it "Mr. Madison's War," because it was bad for business, and since New England was the only place where the Federalists remained popular, they opposed the war, too. For the 1812 election, the Federalists supported an antiwar Democratic-Republican, De Witt Clinton (New York City mayor and George Clinton's nephew), instead of nominating their own candidate to run against Madison. By 1814, things looked so bad that some Federalists in Massachusetts, Connecticut and Rhode Island considered seceding from the United States, and rejoining Old England. In December several of them met in Hartford to discuss this move, and they sent a delegation of "ambassadors" to Washington, to deliver a list of grievances and demand the passing of several constitutional amendments as a solution. By the time the delegation arrived, however, the war was over, and everyone had heard of Jackson's victory at New Orleans, so the Federalists looked very silly, and more than a little treasonous. They never recovered from that, and the Federalist candidate in the 1816 election, New York Senator Rufus King, only won three states (Connecticut, Delaware and Massachusetts), so after 1816, the party faded away.

The Era of Good Feelings

The end of the War of 1812 left Americans in an optimistic mood that lasted for a whole decade, the so-called "Era of Good Feelings." The country continued to grow, and no enemy threatened it, inside the borders or outside. And with the disappearance of the Federalists, the United States became, for the only time in its history since Washington, a one-party nation, meaning there was little of the partisan bickering that has been so common among politicians more recently. Even the ruling Democratic-Republican Party started to break up; its congressional caucus stopped meeting, and no conventions were held, now that they had no opponents challenging them.

Anyway, after Jefferson the philosopher and Madison the lawgiver, the next president was James Monroe. In Madison's administration he had been Secretary of State, and briefly Secretary of War, and while he didn't have as many accomplishments as his predecessors, he suited a nation that was in a relaxed postwar mood. Since the United States was in such good shape, his main task was to make sure it stayed that way, so you can call him Monroe the manager. Along that line, he tried to pick a Cabinet that equally represented different parts of the country; he named John C. Calhoun, a Southerner, as Secretary of War, and John Quincy Adams, a Northerner, as Secretary of State. He did not have any outstanding Westerners, though, because his first choice from the West, Henry Clay, said no (Clay wanted the job Adams got).

Monroe kept the nation at peace by resolving border disputes with Britain and Spain. Now that the northern plains had been explored, folks realized that the wandering US-Canadian border west of the Great Lakes didn't make much sense, so Monroe secured a new treaty with the British, the Anglo-American Convention of 1818, to straighten the border out. This drew a line along latitude 49° N., from the Lake of the Woods to the Rocky Mts., as the new border, so most of the valley of the Red River of the North (in modern-day Minnesota and North Dakota) went to the United States, all of Michigan's Upper Peninsula was confirmed as US territory (see also Chapter 2, footnote #15), and the part of the Louisiana Purchase north of the 49th parallel, in southern Alberta and Saskatchewan, went to Canada.

This is as good a place as any to mention the strangest part of the US-Canadian border, the part around the tiny town of Angle Inlet, Minnesota. The northernmost point in the continental United States, Angle Inlet was awarded to the US by the Treaty of 1783, due to a surveyor's error when that area was mapped. The problem is that Angle Inlet, which had a population of only 54 in the 2020 census, is on a tract of land separated from the rest of the United States, but not from Canada, by the Lake of the Woods. To get there from Minnesota you have to drive through Canadian territory. Now I hear Angle Inlet is a good spot for fishing, so if you want to visit, bring a passport as well as your fishing gear.

In the South, Monroe finished the work of acquiring Florida that Madison had started. Andrew Jackson was the main figure involved in this activity. The Spaniards weren't doing anything with Florida, so it became a base for pirates and unfriendly Indians, and a place of refuge for escaped slaves (see Chapter 2, footnote #28). There was even a "Negro Fort" on the Apalachicola River, which the British had built during the War of 1812, and was occupied by ex-slaves after the war ended, when the British abandoned the fort. An American raid in July 1816 destroyed the fort, and in November 1817 fighting broke out between the US army and the Miccosukee, another tribe based in Florida, starting the First Seminole War (1817-18). The cause of the war was the army driving the Miccosukee from a village in Georgia (Creek tribes had surrendered this area in the treaty of Fort Jackson, but the Miccosukee insisted the treaty did not apply to them).

Soon Jackson had orders to invade Florida, leading a campaign against the Seminole Indians and their Creek allies. He did that all right, but he also did so much more that it takes the most liberal interpretation of his orders to say he carried them out properly: he occupied Pensacola a second time, replaced its Spanish governor with an American colonel, burned Indian villages, executed two British merchants that he caught supplying the Indians, and captured and hanged two Indian leaders, after luring them onto an American ship by flying the Union Jack, leading them to think it was a friendly British ship. Spain protested this heavy-handed behavior, and Secretary of State Adams responded that Spain had better be prepared to give up Florida, if it could not be garrisoned with enough troops to maintain order. The Spaniards took the hint, and like Napoleon, they sold out before they were thrown out; in the Adams-Onis treaty (1819), they handed over Florida to the United States, and the US government agreed to pay $5 million in claims that Florida residents had against the Spanish government. The first American governor of the Florida Territory, from March to December of 1821, was Old Hickory himself.

The main things Spain got from the treaty were a defined border with the United States, and an American declaration that Texas was not part of the Louisiana Purchase. The new Spanish-American border followed the Sabine River, the Red River, longitude 100° W, and the Arkansas River, until it reached the Continental Divide. West of the Rockies, latitude 42° N became the northern limit of Spanish holdings, because Spain still hadn't put any forts or missions north of California.

That left one part of North America where ownership of the land was in question--the Pacific Northwest. Spain was no longer a contender, but the United States, Britain and Russia all had claims here. The Americans offered to resolve this by continuing the US-Canadian border, the one at the 49th parallel, all the way to the Pacific, so that everything south of that line would be American, and everything north of that line would be British/Canadian. Britain said no, and with good reason; they were doing more to exploit the region. By now Hudson's Bay Company had several trading posts on both the Fraser and Columbia Rivers, while the only American settlement was Fort Astoria (founded in 1811 by John Jacob Astor), located at the mouth of the Columbia, in the same neighborhood where Lewis and Clark had their fort. Then other matters came up to keep President Monroe busy, so he did not press the American claim.

The British, however, did put strict limits on the Russian claim. In 1809 Russian trappers showed up on the California coast, and three years later they built Fort Ross, just north of San Francisco. They tried using this fort to claim everything between California and Alaska, but the British wouldn't have that. In 1825 the Russians and British signed a treaty drawing a line between "Russian America" (Alaska) and "British America" (Canada). Starting on the Pacific at latitude 54o 40' N, the border would follow the "crest of the mountains situated parallel to the coast" and would not anywhere go more than 10 marine leagues (approximately thirty miles) from the ocean; then from the neighborhood of Mt. St. Elias the border would go straight north, following longitude 141o W until it reached the "Frozen Ocean." If any of that sounds vague, well, it was, but because Alaska had few residents and visitors for most of the nineteenth century, that definition was good enough; until the Klondike gold rush of the 1890s, it didn't matter much which side of the border you happened to be on. As for Fort Ross, it remained in Russian hands, though it would no longer be used to stake any claims.

During the Monroe years, the United States added not one, not two, but five new states: Mississippi (1817), Illinois (1818), Alabama (1819), Maine (1820) and Missouri (1821). While the first three went through the statehood process without a hitch, Maine and Missouri showed that the issue of slavery, dormant for the past generation, had raised its ugly head again.

What happened was that the Industrial Revolution greatly increased the demand for cotton, because the first factories built with the new machinery were used to produce textiles on a grand scale. Cotton had been grown in the southern states for quite some time, but it wasn't a very profitable crop, due to the need to pick the seeds out of harvested cotton before it could be spun into cloth. Separating the cotton fibers from the seeds by hand is a very labor-intensive job; imagine having to stick salt onto pretzels, one grain at a time, and you'll get an idea of how time-consuming it must have been to clean cotton. Then in 1793, an inventor named Eli Whitney came up with a device that solved this problem, the cotton gin (gin is short for "engine," it has nothing to do with a drink). Using saw teeth, a wire screen and brushes, the cotton gin could clean eight to ten times as much cotton in the same amount of time (it did even more once it was harnessed to a steam engine). Now that farms could grow enough cotton to meet the demands of the factories, and make a good profit on it, cotton replaced tobacco as the chief crop of the South. It also increased the demand for slave labor to work those farms, now that they were competitive with farms and industries using paid workers.

Under Presidents Washington through Madison, those who opposed slavery had been quiet, because they hoped that like Europe and the Northern states, the South would eventually grow tired of keeping slaves. Instead, they now saw the trend going the other way, and as the number of slaves increased, the slaveowners defended their "peculiar institution" more vigorously. Because of the controversy, every new state had to announce, when it joined the union, whether it would allow slavery. So far, the number of slave states vs. free states had been balanced; when Alabama came in, there were eleven of each. Then Missouri announced that it would become a slave state, upsetting the balance. Seeing slavery spreading when it should have been shrinking, Northerners cried "Enough!" and introduced an amendment in Congress that would allow Missouri's statehood, on condition that no more slaves be brought into Missouri, and that those already there would be gradually emancipated. The South's response was equally strong; whereas Southerners in the 1780s had agreed to let the territory northwest of the Ohio River go free, now they fought tooth and nail to keep slaves in Missouri, and made it clear they would do the same with any other part of the Louisiana Purchase.

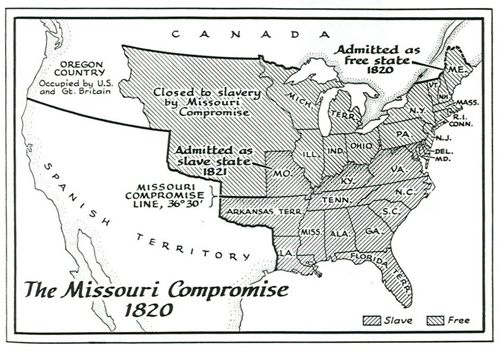

In the end a compromise saved the day: Northerners would let Missouri be a slave state, but to restore the balance, Southerners would have to let Maine, which had applied for statehood in the meantime, break away from Massachusetts and become a free state. For the rest of the former Louisiana Territory, a line was drawn at 36° 30' N (the latitude of Missouri's southern border); all new states north of that line would be free, and all states south of it would be slave states. This agreement, the Missouri Compromise of 1820, was chiefly the work of Henry Clay, and for this he was given the nickname "the Great Compromiser." Still, the days leading up to the Compromise saw the most bitter debate Americans had experienced in years. One man who understood the passions raised by the slavery question was former president Jefferson: "This momentous question, like a fire-bell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror. I considered it at once as the knell of the Union. It is hushed, indeed, for the moment. But this is a reprieve only, not a final sentence." It may also have been the reason why there were no more new states until 1836; folks probably feared that adding states would require another "Missouri Compromise" to win approval in Congress.(33)

The terms of the Missouri Compromise.

Despite the tensions caused by the controversy over Missouri and slavery, Monroe remained overwhelmingly popular. In the 1820 election, he won by the largest landslide of anyone after Washington; except for one New Hampshire elector who cast a ballot for John Quincy Adams, nobody voted against him. For his second term, the main event was the Monroe Doctrine. During the Napoleonic Wars, France had conquered Spain, leaving the Spanish colonies overseas on their own. The French occupation of Spain lasted only six years, but afterwards, when the Spanish monarchy tried to restore the old system, the colonies decided that they liked governing themselves. In Chapter 2 we saw the English colonists of North America start the American Revolution, when King George III tried to strengthen his power; now the Latin American colonies were in revolt for similar reasons. In 1821, just two years after the Adams-Onis Treaty, Mexico declared independence from Spain, so the treaty was Spain's last act on the North American mainland. The northern frontier of the Spanish Empire now became the northern frontier of Mexico. Mexico was more willing to trade than Spain was; in the same year it allowed the opening of the Santa Fe Trail, which ran from Independence, Missouri to Santa Fe, and soon caravans of wagons loaded with merchandise were routinely traveling along it.

Many in the United States favored immediate recognition for the new nations south of the border, but President Monroe didn't want to risk a war with Europe over it. For a while war did appear likely, because the general mood in post-Napoleonic Europe was ultraconservative, against republics and revolutions of any kind. In 1823 France offered to help Spain regain control over her colonies, and there was talk of Russia, Prussia and Austria getting involved as well. For the British this was too much, and the British Foreign Minister, George Canning, proposed that Britain and the United States join in warning the rest of Europe against intervention on the other side of the Atlantic. Former presidents Jefferson and Madison agreed, but John Quincy Adams argued that an independent US foreign policy would be better than acting as Great Britain's junior partner: "It would be more candid, as well as more dignified, to avow our principles explicitly to Russia and France, than to come in as a cockboat in the wake of the British man-o-war." Eventually Adams won over the rest of the Cabinet to this idea, so in a speech to Congress, Monroe put forth three principles that are now called the Monroe Doctrine:

- The western hemisphere is no longer open to European colonization.

- However, the United States will recognize all existing European colonies.

- The United States wants trade and friendly relations with Europe, but will not get involved in European affairs.

Adams Redux

"All good things must come to an end," as the saying goes, and that included the "Era of Good Feelings." We mentioned tensions rising over slavery; there was also an economic depression in 1819 to take away people's good cheer. By the end of Monroe's second term, most Americans were in the mood for a change, and so was he. The 1824 election was the first in which ordinary people got to vote, but it showed that the system for choosing a president still had some bugs in it. The favorite candidate of Congress, Treasury Secretary William Crawford, had suffered a stroke a year earlier, so most felt he wasn't fit to be elected. Consequently three other politicians, Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay, also ran.(34) Because there were now four candidates, nobody got the required majority of electoral votes. For the second (and so far last) time, the House of Representatives was required to pick a president. Congressmen were only allowed to vote for the top three candidates, and that eliminated Clay, who came in fourth place. Clay disliked Jackson (he felt that winning the battle of New Orleans was not enough to qualify someone for the White House), so he told his supporters to vote for Adams. He figured correctly that Adams would not be a very popular president, and that he would not have to wait more than four years to succeed him. Adams was elected, and he returned the favor by picking Clay to be his Secretary of State.

Jackson had gotten the largest share of both popular and electoral votes, so he knew he was the most popular man in the country; naturally he cried foul when he heard of Clay's political dealing, calling it a "corrupt bargain." Jefferson, Madison, Monroe and Adams had all been Secretaries of State before moving into the White House, so that job now looked like an apprenticeship for the presidency, even more so than the job of vice president.(35) Jackson spent the next four years accusing Adams and Clay of stealing the election, insuring that Clay would not have an easy succession after all, and that Adams, like his father, would only be a one-term president.(36)

Up to this point, Adams was mainly known for foreign policy achievements, but his policy as president was mostly domestic, an infrastructure-building program called "the American System." While much of it was really a continuation of what Monroe had started, Adams deserves credit for supporting the construction of the National Road through Ohio (see footnote #32), the building of several canals, and the creation of a national university and an astronomical observatory. The most ambitious project, the Erie Canal, ran 363 miles through upstate New York from Albany to Buffalo, and since the elevation of the land was 571 feet higher on the west end, it required 82 locks along the way. It also meant draining swamps and cutting down a considerable amount of virgin forest, making the project so expensive that it was considered unfeasible when it was first proposed in 1783. Digging the canal finally got started in 1817, and was finished in 1825. At the ceremony opening the canal, several boats traveled the full length from west to east, bringing a barrel of water from Lake Erie, and when they got to New York City, Governor De Witt Clinton poured the water from the barrel into the harbor, in a ceremony called the "Wedding of the Waters." By connecting the Hudson River with the Great Lakes, and avoiding obstacles like Niagara Falls, the Erie Canal provided a water route to the West. It also encouraged businesses to use New York City as a port, instead of Boston or Philadelphia; over the next generation, New York would grow to become the nation's largest city.

However, the next form of transportation was already on the way; the first American railroad opened in Massachusetts in 1826, so after that, people were more interested in the "iron horse" than they were in canals. In Pennsylvania the editor of one newspaper asked, "What is a railroad? Perhaps some correspondent can tell us." Unfortunately, the word was so new that nobody had an answer for him.

We noted that the presidents before Adams were against funding infrastructure projects, and their attitude will make sense after you hear what else Adams spent taxpayer dollars on. At the time, a veteran of the War of 1812, John Cleves Symmes Jr., was traveling around the country and promoting his theory--that the earth was hollow, and there were big holes in the north and south poles. Mind you, this was decades before Jules Verne wrote A Journey to the Center of the Earth, but even at this early date, most people thought a hollow earth was nonsense, and that there couldn't be anything but rock and magma under our feet. Still, Symmes made believers of those who heard his lectures, and one of them was the president. Adams actually gave Symmes permission to prepare an expedition to the north pole, with the goal of climbing through the hole and opening up trade with the mole people on the world's inside.

No, not those mole people.

This journey to the underworld never got started, because the Adams presidency ended first. His successor, Andrew Jackson, promptly cancelled the expedition. Jackson wasn't interested in exploring any new places; he was more interested in killing the people in places Americans had already explored.

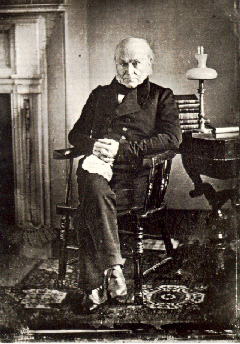

John Quincy Adams was the only president who became a congressman in the House of Representatives after leaving the White House. The camera was invented while he was there, and he posed for this daguerreotype in 1847, making him the earliest president whose photograph exists. One year later he collapsed and died in the Capitol, at the age of 80; I guess retirement was never meant for him.

Old Hickory's Democrats

For the 1828 election, the Democratic-Republican Party, which hadn't really acted like a political party for the past decade, split along regional lines. Evidently the name "Democratic-Republican" was now seen as too cumbersome, because each of the new parties only took half of the old name; the old party's eastern establishment, which supported the reelection of Adams, became the National Republican Party, while the backers of Jackson first called themselves the Jacksonian Democrats, and after he retired, the Democratic Party.(37) A popular rhyme of the day listed the candidates as:

And Andrew Jackson, who can fight."

This time there was no stopping Andrew Jackson. The voters chose him by a landslide, giving him every state in the South and West. Adams supporters tried to prevent his victory, though, by engaging in the most vicious mudslinging since Jefferson was elected. They portrayed Jackson as a cold-blooded killer in the "Coffin Handbills," a notorious series of pamphlets that told how Jackson hanged deserters, massacred Indians, fought duels, and otherwise acted more like a psychopath than a statesman. If Jackson had tried to kill somebody during the campaign, it would have been gold for the Adams campaign, but this time Old Hickory managed to keep his temper; when his friends talked him out of challenging Henry Clay to a duel, he angrily said, "How hard it is to keep the cowhide from these villains."

Jackson's wife Rachel also came under attack, because he had mistakenly married her in 1791, before the divorce from her previous marriage had been finalized, so they were accused of adultery. In fact, the humiliation affected Rachel's health; she died of a heart attack in December 1828, before her husband took office. Jackson blamed her death on his opponents, especially Adams: "May God Almighty forgive her murderers as I know she forgave them. I never can."(38)

Jackson was the first president who did not call either Virginia or Massachusetts his home, and he was definitely of rougher stock than his predecessors. Born in South Carolina in 1767, his father a few days before his birth, and he lost the rest of his family during the American Revolution. In 1780, at the age of thirteen, he took part in his first battle against the British; his elder brother Hugh was killed, and shortly after that, he and his other brother, Robert, were captured. There was an incident in captivity where Jackson refused to clean the boots of a British officer, and the officer struck him on the face with a saber, giving him a scar that he always wore after that. Later their mother got the boys released from a British prison in Camden, SC, but Robert soon died of the smallpox he had contracted as a prisoner, and when Mrs. Jackson volunteered to be a nurse for other American prisoners, the disease carried her off, too. All this gave Andrew a strong disliking of the British, and anybody who looked like them (read: rich Easterners). After he grew up he studied to become a lawyer, and moved with a partner to Nashville, TN, where he ended up spending most of his career. When Tennessee became a state, he was elected as its first congressman, and a year later he was elected to finish an unexpired term in the Senate. After that term finished in 1798, he served as judge of Tennessee's superior court for six years, and then became general of the state's militia, the job he was holding when the War of 1812 broke out. All these activities, combined with a life on the frontier, made him approach everything in a direct, nothing-to-hide way that stood out against the careful manners of those who lived on the east coast; his election meant that those representing the farmers and small businessmen west of the Appalachians were now in charge.

In that sense, Jackson gave America a new kind of president. Because he had a stronger personality than his predecessors, he frequently vetoed bills passed by Congress and disputed the Supreme Court's rulings (in one such challenge, he said, "John Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it!"). For that reason, Americans stopped seeing Congress as the most powerful body of government, and started viewing the president in that role instead. Of course, this led critics to accuse Jackson of having a Caesar complex, as they did with all strong presidents; a contemporary cartoon called him "King Andrew the First," and showed him dressed with a crown and robe, while trampling on the Constitution.

Jackson also gave America a new kind of democracy. Previously "democracy" had been a dirty word of sorts, which was associated with mob rule. Despite their talk about government by the people, the Founding Fathers made it clear that the government they wanted was a republic, not a democracy; when they were looking for ideas to use in the Constitution, they investigated a variety of governments, from those of classical Greece to the Iroquois Confederacy, but the one that provided the most inspiration was the Roman Republic. Jackson, though, felt that more participation from the people would strengthen the nation, so his program for America called for making money more readily available to the common man, and universal male suffrage--giving every white man the right to vote, whether or not he owned property.

Those who had trouble telling the difference between democracy and anarchy felt proven right on the day Jackson became president. After he gave his inaugural address, he invited his audience into the White House for a reception. Thousands of ordinary folks swarmed in, introduced themselves to government officials, tore down the curtains, broke china and glass, climbed over tapestried chairs in muddy boots, and smeared the carpets with liquor and food. Jackson had to escape through a back door, and the crowd only left when some punch bowls were placed outside to lure them. Joseph Story, a Supreme Court justice and an Adams supporter, described the scene by saying "the reign of King Mob seemed triumphant." The opposite view was taken by a pro-Jackson newspaper, reporting that "it was a proud day for the people. General Jackson is their own President."

Early in Jackson's administration came a crisis that threatened to split the United States in two. Thanks to the Industrial Revolution, the British were selling manufactured goods, especially clothing, at prices lower than what American factories could match. To protect American industry, Congress, led by Massachusetts Senator Daniel Webster, passed a tariff on imported manufactured goods in 1828, and then-President John Quincy Adams signed it, without realizing that this would make him look like the creator of a second Embargo Act (the Ograbme was briefly brought back to symbolize Adams during the 1828 election). Southerners called the tariff the "Tariff of Abominations," for it hit them both coming and going; they had to pay more for manufactured goods, because the mostly agricultural South made few of its own, and the British bought less cotton, because they had fewer customers for the finished product. They argued that the tariff was only good for the North, and promoted an idea they called the Doctrine of Nullification, which basically says that a state has the right to ignore a federal law that is hurting it badly. The state which argued the strongest for nullification was the same state that so far had been the biggest supporter of slavery--South Carolina--and in the person of John C. Calhoun, South Carolina had a loud voice in Washington. In the debate that followed, Webster came to be seen as the champion of the North (and the Union), while Calhoun became the chief defender of the South.

Calhoun had stayed on as vice president after John Quincy Adams left the White House, because Jackson was the least healthy president to date, and Calhoun saw this as a chance to move into the top spot, should Jackson's health fail before his term ended. Although Jackson had also come from South Carolina, his sympathy for the state of his birth could only go so far; once he remarked that South Carolina was "too small to be a republic, too large to be a madhouse." To him talk about nullification was treasonous, and he let it be known that he would hang anyone who tried to leave the United States over this issue, starting with Calhoun, and lead an army of 35,000 against South Carolina, if necessary. A bitter rivalry between him and Calhoun followed, which peaked at an 1830 dinner honoring Thomas Jefferson's birthday. When the participants were invited to offer toasts after the meal, Jackson went first; he raised his glass of wine, looked fiercely at Calhoun, and shouted "Our federal Union: it must be preserved!" Calhoun turned pale as a ghost, but managed to shout back, "The Union: next to our liberty, most dear!" They never got along after that, and in 1832 Calhoun resigned from the vice presidency so he could become a South Carolina senator, a job that gave him more power. To replace him, Jackson picked his best friend from the North, Martin Van Buren.(39)

Slavery was another issue that caused considerable controversy at this time, though most Americans were not ready to fight over it. The Abolitionists were increasing in numbers, and getting louder, because, as we noted earlier, they had hoped the South would outgrow slavery, while pro-slavery advocates feared that the North would legislate slavery out of existence, but neither happened. In the nation's early years, Washington, Jefferson, Clay, and even John Randolph (a Virginia congressman known for his eccentric behavior, biting wit, and strong defense of his home state) were willing to see some blacks freed, but they thought making major changes to the institution would lead to trouble. Others, however, had gotten tired of waiting; Abolitionists noted that 300 slaves were born every year, for each one who gained his freedom.

The most famous Abolitionist ad was this picture of a crying black man in chains.

The Abolitionist movement gained a bold new voice when a Boston journalist, William Lloyd Garrison, began publishing a weekly newspaper, The Liberator. He had been involved in early programs to help blacks, like the American Colonization Society, which sent ex-slaves to Liberia (see footnote #33), but this did not produce the quick results he wanted, so he began a war of words, demanding that slavery be abolished, unconditionally and immediately. In The Liberator's first issue, published on January 1, 1831, Garrison explained his actions with these words:

"I am aware that many object to the severity of my language; but is there not cause for severity? I will be as harsh as truth, and as uncompromising as justice. On this subject, I do not wish to think, or to speak, or write, with moderation. No! No! Tell a man whose house is on fire to give a moderate alarm; tell him to moderately rescue his wife from the hands of the ravisher; tell the mother to gradually extricate her babe from the fire into which it has fallen; - but urge me not to use moderation in a cause like the present. I am in earnest - I will not equivocate - I will not excuse - I will not retreat a single inch - AND I WILL BE HEARD. The apathy of the people is enough to make every statue leap from its pedestal, and to hasten the resurrection of the dead."

Garrison was a controversial figure because he had little, if any, respect for the men and institution that created the United States. He called the Constitution "a covenant with death and an agreement with Hell" because it permitted slavery, and even burned some copies of it in public. And while he preferred nonviolent methods of getting things done, the meetings where he spoke tended to be violent anyway, because of the angry mobs that showed up. The worst example was in 1835, when he agreed to speak at an Anti-Slavery Society lecture because the original speaker, the British Abolitionist George Thompson, could not attend. A mob came looking for Thompson, and failing to find him, chased Garrison through the streets of Boston and nearly lynched him. Garrison had to spend the night in a jail to hide from his pursuers, and then left the city for several weeks. Other followers of Garrison were murdered by mobs, like the Reverend Elijah Parrish Lovejoy, whose printing press in Illinois was destroyed after he was shot in 1837.

Later in 1831 came the Nat Turner Slave Revolt in Virginia. Nat Turner was an uncommonly resourceful slave, and called a prophet by other slaves because he saw visions from time to time. When he saw a solar eclipse in 1831, he took that as a sign to rise up and kill all whites. It didn't last very long; within 48 hours the revolt was suppressed, after 55 whites and more than a hundred blacks were killed. Turner himself was captured in a swamp two months later, tried and executed. Although Garrison's newspaper only had a circulation of about 400 at this date, the whole South blamed the revolt on him. Copies of The Liberator were burned in several places; white Northerners were beaten; a wave of lynchings happened away from the cities; the state of Georgia offered a reward of $5,000 for the arrest of Garrison. In Washington, Southerners introduced a "gag rule" in the House of Representatives, that banned discussion of the slavery issue.

Despite all this, Garrison's voice was indeed heard. He continued to publish The Liberator until the end of 1865, allowing him to chronicle the entire struggle to abolish slavery; over half of his subscribers were black, because he was the first white editor who made much sense to them. In the early 1840s he encouraged Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass, two ex-slaves, to tell their stories and become leaders in the movement, though Douglass later found Garrison too radical for his tastes (Douglass didn't believe in burning the Constitution because he saw it as a document promoting freedom, if interpreted right).

Meanwhile in Washington, Andrew Jackson continued looking for ways to limit the power of rich Easterners. His feelings against them extended to their conservative money policy, which he felt hindered western expansion. The most visible symbol of eastern money was the National Bank, also known as the Second Bank of the United States. The charter for the original National Bank, Alexander Hamilton's creation, had expired in 1811, and many at the time felt the Bank was unconstitutional--the Constitution specifically gave Congress the power to coin money and regulate commerce--so the first Bank was allowed to die a natural death. Then the War of 1812 came along, and James Madison had a hard time financing it without a bank; in 1816 he changed his mind and granted another twenty-year charter for one, hence the name "Second Bank." Jackson, on the other hand, saw the Bank as a den of fraud and corruption, due to shady lending practices and land speculation during its early years, and he blamed it for boom-and-bust cycles in the economy that benefitted the creditor and investor but tended to make workers and farmers go bankrupt. On top of that the Bank was heavily involved in politics; it routinely gave money to several politicians, like Daniel Webster, subsidized newspapers across the country, and kept the most aggressive lobby in Washington.

At first Jackson was just going to wait for the Bank's charter to expire, but the head of the Bank, Nicholas Biddle, preferred a showdown to waiting, and applied for a new charter in 1832. When Congress passed that bill, Jackson confided to Martin Van Buren, "The Bank, Mr. Van Buren, is trying to kill me, but I will kill it." Then he vetoed the bill, withdrew the government's money from the Bank, and ordered that henceforth money collected from taxes would be deposited in smaller banks.

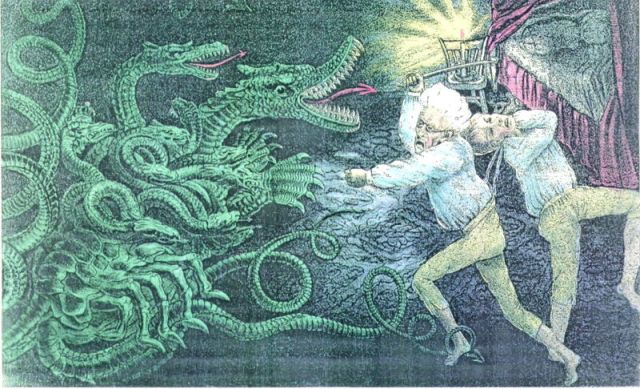

Democratic cartoon of 1832 shows Jackson having a nightmare; the National Bank has turned into a hydra-like monster, and he is attacking it. The other character, holding onto Jackson by his suspenders, is Jack Downing, an early representation of the average American citizen, trying to get Jackson back in bed.