| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of the South Pacific

Chapter 5: Oceania Since 1945, Part IV

Part I

| First, A Word on the Cargo Cults | |

| The Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, and Nearby Atolls | |

| Australia: The Menzies Era | |

| Rabbits Gone Wild | |

| Recolonial New Zealand |

Part II

| Independence Comes to the Islands | |

Part III

| The Australian Constitutional Crisis | |

| Australia in Recent Years | |

| New Zealand: Labour and National Reforms |

Part IV

The Smaller Island Nations Since Independence

The other nations covered in this narrative (besides Australia and New Zealand) have not enjoyed happy years since their colonial overlords turned them loose. Indeed, when I started writing this chapter, I thought of calling it “Paradise Today,” but then realized that the peoples living on most South Pacific islands would disagree with their present-day homes being called “Paradise.” Because most of them live near the beach, in a place that is warm all year round, the impression people from non-tropical climates get is that Pacific islanders are on vacation all the time. Yet while we have noted that this setting has given the islanders a laid-back outlook on life, for a complete picture, we should also note that the lack of resources on many islands has also kept the islanders in poverty, and they don’t live as long as most people in today’s world.(32)

In densely populated Third World countries like the Philippines, many folks get jobs abroad, and the remittances they send back to their families provide a boost to the homeland economy. As with tourism, this has brought money to South Pacific island countries, but not enough, due to their low populations. One resource all the islands do have is coconut trees, and they grow as many coconuts as they can, but again, the shortage of land and workers means that they cannot produce enough to compete with Southeast Asian coconut growers.

What this means is that all the nations in this group suffer from a bad trade deficit; none of them can generate an income big enough to cover the cost of what they import. As a result, they are dependent on foreign aid from the nations that used to rule them, and also on foreign investors who will develop their lands, hopefully without swindling the natives. Often, those investors have found the islands (with their current governments) to be nicer places than the natives have -- that is why critics talk about “neo-colonial” regimes, and compare them with the colonial regimes of the past.

Of course the events and current situations are different for each nation, so next we will take a look at them separately, to fill in the rest of the details.

The Federated States of Micronesia (FSM), Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI), and Palau

Not much has happened in these three Micronesian nations since the United States granted them independence. In fact, the Americans did not completely leave; we noted earlier that all three states need the US to defend them and provide financial aid. After the excitement of World War II and the postwar nuclear testing, this part of the Pacific has gone back to being the quiet backwater that it was for most of history. Of course, this is because of the low populations mentioned previously (see footnote #21). All three nations set up governments modeled after that of the United States, but to an American they appear incomplete; e.g., the FSM has a unicameral Congress and no political parties, because with the population divided into many tribes and languages, it is difficult to form any organization that encompasses more than one island. For all three, present-day concerns include high unemployment, overfishing, and their dependence on US aid.

Here's a fun fact about Micronesia; because it does not get many visitors these days, Micronesia does not require foreigners to get visas. Anyone with a valid passport can come here and stay for up to 90 days, with no questions asked.

On the international scene, the FSM and RMI joined the United Nations in 1991; Palau joined in 1994. The original Compact of Free Association (COFA) between the three nations and the United States was due to expire after fifteen years, as we noted previously. Therefore the Compact was renewed in 2004 and 2023; now it is in force until 2043. In return for fixing the immediate financial shortfall of the islands, the United States was allowed to continue using the missile test range on Kwajalein Atoll.

In 2011, the Marshall Islands declared more than 772,000 square miles of ocean to be off limits for shark fishing. This is the world’s largest shark sanctuary.

Half of Palau’s population (estimated at just over 25,000) lives on one island, Koror. The capital was also located there until October 2006, when it was moved to Melekeok, on the largest island, Babelthuap. A concrete cantilever bridge connecting Koror with Babelthuap had been built in 1977, and in 1996 it collapsed, crippling the country’s transportation and communications. It was replaced first with a pontoon bridge, then with a new suspension bridge in 2002.

Fiji: Too Early to Tell

Did you think Fiji’s ethnic tensions, between native Fijians and the Indo-Fijian community, were resolved when Britain granted independence in 1970? On the contrary, they got worse after the British departure. Because most people living on Fiji respected the rule of law, and it had fully developed political parties at the time of independence, the events which happened from 1987 onward were unprecented in South Pacific history, and came as quite a shock.

For the first seventeen years, Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara and his Fijian Alliance Party (FAP) ran the government. They won the first post-independence election in 1972, and in January 1973, the highest-ranking Fijian chief, Ratu Sir George Cakobau, was sworn in as governor general, succeeding Sir Robert Foster, the last governor of the colonial era. From 1978 to 2002, Fiji contributed troops to the UN peacekeeping force in Lebanon; so far that has been Fiji’s main activity abroad. Its international image was also helped by the fact that only 3 percent of the Fijian budget was paid for by foreign aid, the lowest percentage of any Pacific island nation. However, the prosperity of the 1970s depended on sugar prices remaining high, a risky proposition, and Fiji’s reputation as one of the Third World’s havens of democracy and multicultural harmony would be called into question soon enough.

The first sign that trouble was on the way came with the election of March 1977; the Indian-led National Federation Party (NFP) won a majority of seats in the House of Representatives, though the FAP got more votes. Then the NFP failed to form a government because of internal divisions, combined with the concern that indigenous Fijians would not accept Indo-Fijian leadership. Governer general Cakobau asked Ratu Mara to stay in power and form a caretaker government. Naturally the Indian politicians protested, and they voted no-confidence, which meant a new election needed to be held in September. This time the FAP won a solid majority in both seats and votes, so the Fijians remained in charge.

The early 1980s saw sugar prices drop and the country’s foreign debt rise, and the worsening economy led to new tensions between the Fijian minority and the Indo-Fijian majority. Fijians came to see the Indians as shopkeepers obsessed with making money, but this was just another stereotype, because not all Indians were in business for themselves and unlike the Fijians, they could not own farmland, only lease it. The FAP was also blamed for not doing enough to advance the Fijian standard of living. In response, the working class formed the Fiji Labour Party (FLP), and in Fiji’s fifth post-independence election, the FLP formed a coalition with the NFP and won a stunning upset victory (April 1987). Akthough the new government was headed by a Fijian, FLP leader Timoci Bavadra, Indian legislators were in the majority, so protests erupted immediately.

On May 14, 1987, the first day of the new session of Parliament, Lt. Col. Sitiveni Rabuka marched into Parliament with a handful of soldiers and overthrew the government in a bloodless coup. Rabuka said he did it to return political power to the Fijians and demanded that changes be made to the constitution to guarantee that the Fijians would always be in charge. The next day, Ratu Mara announced he would serve on the provisional government's council of ministers, and to many Fijians that made the coup legal. The Great Council of Chiefs also endorsed the Rabuka regime, and authorized it to amend the constitution. Then because the outside world was voicing its disapproval, Rabuka handed control over the government to the governor general, but remained in command of the army and police.

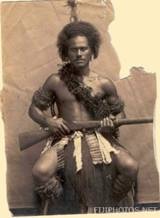

Sitiveni Rabuka, early in his career.

After four months of negotiations failed to set up a new government, Rabuka staged a second coup on September 25, 1987. This time he didn’t do things halfway; the constitution was thrown out, and Fiji was declared a republic. Indo-Fijians began fleeing the islands because they were now targets of discrimination (50,000 would leave by 1992), the government of India protested, Fiji was expelled from the Commonwealth, and several nations refused to recognize the Fijian Republic. In December Rabuka stepped down as the temporary head of state, Governor-General Ratu Sir Penaia Ganilau was appointed the first President of the Fijian Republic, Ratu Mara became Prime Minister again, and Rabuka became Minister of Home Affairs.

The coups of 1987 failed to improve the lives of most indigenous Fijians, and because the coups had destroyed a sense of legitimacy, Fijian society began to come apart. Rifts soon appeared between eastern and western chiefs, between high chiefs and villages chiefs, between people in the cities and the countryside, and between the church and trade unions. The economy was hit especially hard, because the outside world didn’t want to buy Fijian sugar or send foreign aid, and tourists were discouraged from coming.(33)

To put Fiji’s house back in order, a new constitution was introduced in July 1990. This one gave considerable political power to the Great Council of Chiefs and the military, and gave the Indo-Fijians only a minor role in the government. Of course the Indo-Fijian political leaders declared themselves against this constitution, calling it racist and undemocratic, but there wasn’t much they could do about it, since the recent exodus of Indo-Fijians had reduced them to a minority. The Great Council of Chiefs disbanded the FAP, because of its multi-ethnic membership, and formed a new party called SVT (Soqosoqo-ni-Vakavulewa-ni Taukei, or the Party of Policy Makers for Indigenous Fijians). Rabuka resigned from the military, became the SVT party leader, ran for prime minister, and was elected to that position twice, in 1992 and 1994.

Because the constitution was unacceptable to everyone except indigenous Fijians, a constitutional review commission was set up to investigate the constitution’s failings and suggest improvements. It recommended bringing back participation for all ethnic groups; one proposal called for leaving the presidency reserved to a Fijian, but removing all ethnic restrictions on the prime minister’s job. The government accepted most of the recommendations, and another constitution was produced in 1997. That year also saw Rabuka apologize to Queen Elizabeth II for the 1987 coups, and he atoned by presenting her with a sperm whale's tooth (a traditional gift, called a tabua). One month later, Fiji was allowed to rejoin the Commonwealth. The first elections afterwards came in 1999, and this time the FLP won; Mahendra Chaudhry became the first Indo-Fijian prime minister.

It looked like Fiji’s political problems were solved at this point, but no such luck. The economy did not get better, there were arson and bomb attacks in Suva, the capital, and Fijian legislators launched an unsuccessful no-confidence motion. Then on May 19, 2000, a group of armed men took 30 hostages, including Prime Minister Chaudhry. A native Fijian businessman, George Speight, was the leader of this coup. He demanded the resignation of Chaudhry and President Ratu Mara, and that the 1997 constitution be abandoned. Whereas the 1987 coups had been bloodless, more than a hundred Indian-owned shops and business were looted and burned in Suva, in the days following this coup. President Ratu Mara tried to defuse the crisis by removing Chaudhry from office, but with lawlessness increasing, Mara was soon compelled to step down, too. The commander of the armed forces, Commodore Josaia Voreqe “Frank” Bainimarama, declared martial law. Eight weeks of negotiation between Speight's rebels and Bainimarama's soldiers followed; at the end of that time, the hostages were released and the 1997 constitution was revoked. The military appointed Laisenia Qarase as prime minister, and the Great Council of Chiefs appointed a former vice president, Ratu Joseph Iloilo, as president of the interim government. Speight was arrested and charged with treason, convicted, and sentenced to death, but that sentence was quickly commuted to life imprisonment, which he is serving now.

Two court rulings, in November 2000 and March 2001, declared the interim government illegitimate, upheld the 1997 constitution, and called for new elections in 2001. In that election, Lasenia Qarase’s party, the Fiji United Party (SLD), won 31 out of 71 seats, not a majority, but Qarase retained the prime ministership, and went on to appoint only indigenous Fijians and SLD members to the 18 cabinet positions. Unfortunately, the divisions caused by the 2000 coup did not heal, and from 2004 onward, tensions between the government and the military started to increase again. The main source of tensions was the military’s attitude that the government was too lenient with the 2000 coup plotters. When Qarase narrowly won re-election to a second term in May 2006, he formed a coalition government with the FLP.

That coalition and the gridlock lasted until December 5, 2006, when Commodore Bainimarama seized power in another coup (the fourth if you’re keeping track). Bainimarama dismissed Prime Minister Qarase and declared himself acting president. Though he is a native Fijian, he did it because he opposed some proposals from Qarase; one would have granted amnesty to those involved in the 2000 coup, and two would have discriminated against the Indian minority where land rights were concerned. One month later he announced he was reinstating Ratu Iloilo as president; Iloilo then announced Bainimarama would become the interim prime minister, a move that meant the military would stay in control.

Commodore Bainimarama in 2006. From Britannica.com.

After that, things stayed quiet for two years, until the Court of Appeal ruled in April 2009 that the current government was illegal and new elections need to be held as soon as possible. Instead of complying, President Iloilo declared martial law; the constitution was revoked, all judges were dismissed, and foreign journalists were expelled. Bainimarama was confirmed as prime minister again, and he announced that elections would not be held until 2014. The following July, Iloilo, now eighty-eight years old, announced his retirement; he was replaced by another military man, Ratu Epeli Nailatikau. In September 2009 the Commonwealth suspended Fiji’s membership, declaring that the country was not returning to democracy.

2012 saw the abolition of the Great Council of Chiefs, which Bainimarama called an outdated and divisive relic of the colonial era. The government drew up the latest constitution in 2013, and when the promised election was held on Sept. 17, 2014. Bainimarama's newly formed Fiji First party won with 59.2% of the vote. Because Bainimarama had resigned from the military six months earlier, he would serve as a civilian prime minister from now on. It had taken Fiji eight years to go through its so-called “transitional period.” Then in October 2015 Parliament elected another former military man, Jioji Konrote, as the current president.

The main thing Fiji’s recent history has taught us is that we cannot know for sure when the story is over. The islands may be quiet now, but who’s to say the ethnic tensions have been settled, or that there won’t be more political unrest in the future? If there is a place in this narrative that is likely to require an update in a few years, Fiji is it. But don’t let Fiji’s periodic instability put you off from visiting, if you happen to be in the South Pacific. The natives quit killing and eating visitors a century and a half ago, and are certain to make you feel welcome (see the previous footnote). And who knows, maybe this time they have learned enough from their past experiences to keep the racial disharmony and coups from repeating themselves.(34)

Kiribati: Every Day and Every Year Begin Here

Since independence in 1979, Kiribati has remained politically stable. The biggest issue was Banaba: that island ran out of phosphate, the local economy crashed as a result, and most Banabans are now living in Fiji (see footnote #17). On the other islands, overcrowding has been a problem; at least foreign aid organizations think so. In 1988, an announcement was made that 4,700 residents of the main island group would be resettled on less-populated islands.

For those too young to remember the year 2000, it was both a time of anticipation and apprehension. The reason for the anticipation was obvious; not since the Dark Ages had anyone in Western civilization seen the beginning of a new millennium. As for the apprehension, that came from the Y2K scare; in the twentieth century, computers used two digits, not four, to keep track of years, so computer-literate folks were concerned that when computers made the transition from the year 99 to 00, it would cause software failures worldwide.

Anyway, the first nations to celebrate each new year are all in the South Pacific, thanks to the earth's orientation at that time (with the southern hemisphere tilted towards the sun) and the International Date Line. To understand how this came about, we have to go back to the International Meridian Conference of 1884. At that event, forty-one astronomers and diplomats from twenty-six nations gathered in Washington, DC, to decide how time and longitude would be measured worldwide. We saw in Chapter 2 that the British measured an object's longitude by how far east or west it was from an imaginary line running through an observatory at Greenwich, England. Because Britain led the world in science and cartography (map-making) in the nineteenth century, most of the world came to accept this idea. So at the conference, the Greenwich line officially became Longitude 0°, the Prime Meridian.

Next on the agenda, the conference had to decide which longitude line would be used to mark the place on earth where each new day began. For this purpose, any meridian would do, but putting it in the middle of a highly populated area would have caused lots of calendar-related confusion. If the Prime Meridian had doubled as the date line, for instance, England would have been permanently split; the date in Dover would always be different from the date in Bristol, and anyone in the heart of London could go back in time by traveling east a few miles. In the end, it was decided that the line on the exact opposite side of the world from the Prime Meridian – Longitude 180° -- was the most suitable place to put a date line. Not only did this line run through water almost everywhere, but the nearest cities were a few hundred miles to the west (in New Zealand).

Although both the conference and the date line were called “international,” they have never been backed by international law, so in practice the International Date Line zigzags, to make life more convenient for the nations around it. On its way from north to south, it zigs east to make sure that all of Siberia is west of the line, and then it zags west to keep the Aleutian Islands with Alaska. After that it follows the 180th Meridian to the equator, and then in the southern hemisphere it meanders east to put Tonga, all of Fiji, and the Kermadec and Chatham Islands on the same side of the line as New Zealand, the nation they have the most commerce with. However, that arrangement left Kiribati straddling the line, with its islands distributed between three time zones, two of them east of the line and one west of it.

Now in the 1990s, there was a competition between Tonga, Fiji, Kiribati and New Zealand for tourists. All of them tried to make a quick profit by advertising that because they would be the first countries to begin the year 2000, tourists looking for a good place to enjoy the turn of the millennium should spend it with them. Then suddenly, on the first day of 1995, Kiribati won the contest, by moving its islands ahead 24 hours in time. What happened was that the two eastern time zones were changed from UTC-11 and UTC-10, to UTC+13 and UTC+14, respectively. Previously Tonga had used the UTC+13 time zone, but nobody had ever used UTC+14; Kiribati made it up to put the whole country west of the International Date Line. To give an idea of how odd this can be, Hawaii’s time zone is UTC-10, so while a clock in eastern Kiribati will show the same time as a clock in Hawaii, the dates on their calendars will always be different. Officially Kiribati said it changed its time zones to end the nation's perpetual division between two dates on the calendar, but pulling this trick also meant their easternmost islands would experience New Year's Day a full hour before Tonga, and two hours before Fiji and New Zealand(35); what's more, the world would henceforth have 26 time zones.

It also made for a weird-looking International Date Line, which now forms the outline of an axe in the mid-Pacific.

Readers may be amused at Kiribati’s fishing problem. Because most of their islands are just little coral caps on top of the ocean, and Banaba’s phosphate is gone, most of Kiribati’s 102,351 residents (the estimated population in 2013) have two ways to earn a living: by fishing or growing coconuts.(36) Unfortunately, the fishermen were catching too many fish, enough to deplete the surrounding waters. Well, one of the primary rules of governing is that you can reduce a certain behavior by taxing it, and increase that behavior by subsidizing it. Therefore, the Kiribati government decided to subsidize the coconut growers. The idea was that if you paid the people to grow more coconuts, they would do less fishing, and you would end up with more fish in the ocean and more money in the hands of the people. A win-win situation, right?

Some time after the policy was implemented, Sheila Walsh, a researcher from Brown University, conducted a study to find out how well it was working. Instead of decreasing fishing, she learned that the people were fishing 33 percent more, and the fish population had dropped 17 percent. The plan had failed to take two factors into account. First, coconut growing is not a full-time job. When the growers were not planting trees, harvesting coconuts, or turning coconut meat into copra, they had plenty of free time, and I have already said that the tropical island environment encourages people to take it easy, so instead of working as hard as they did before to make more money, the people now could earn the same amount of money, while working less.

The other forgotten factor was that people fish for fun. Remember the bumper sticker which says “A bad day’s fishing is better than a good day at work”? Well, like the late, great Virgil Ward, the people of Kiribati enjoy fishing, and that is what they did with their leisure time. And if they felt they needed more money, they could always sell their catch. Oops!

In 2002, Kiribati passed a controversial law that allows the government to shut down newspapers. This legislation probably had something to do with the launching of Kiribati's first successful non-government-run newspaper.

These days, Kiribati’s main concern has been the possibility that global warming will melt the world’s glaciers and drown the country. Because the highest point of land is only ten feet above sea level, the oceans wouldn’t have to rise too much to put all of Kiribati underwater. As far as I know, there hasn’t been any detectable rise in the Pacific’s sea level yet, just some beach erosion, but Kiribati isn’t going to wait for it to happen. In June 2008 Anote Tong, Kiribati’s fourth president (2003-2016), asked Australia and New Zealand to accept Kiribati citizens as permanent refugees, declaring that the country had reached "the point of no return." Then in 2014, after two years of negotiations with Fiji, Kiribati bought eight square miles of land on Fiji’s second largest island, Vanua Levu. President Tong announced this would allow Kiribati’s entire population to move to Fiji, and called it “migration with dignity.” Since the islands have not become uninhabitable yet, the recently acquired estate will probably be used for supplemental food production. Finally, the government is considering building artificial islands, structures resembling offshore oil-drilling platforms, so some of the people can continue to live near the ocean.

Tuvalu: The First Nation to Go Under?

If Kiribati is worried about getting submerged, you can imagine how Tuvalu feels. Tuvalu has even less land available, and on their nine-island chain Tuvalu’s tiny population has cut down trees for fuel and dug up sand for use in cement/concrete. If a rising sea level doesn’t make Tuvalu disappear, man-made erosion will.

Both Kiribati and Tuvalu waited two decades after independence before applying to join the United Nations; Kiribati joined in 1999, Tuvalu in 2000. The reason for the delay was money; both countries had trouble coming up with the funds required to pay the UN’s membership fees. For Tuvalu, the money became available by a stroke of luck. In the early 1990s, as ordinary people (not just computer scientists) gained access to the Internet, two-letter country codes were assigned to each nation and territory. Under this system, Canada got .ca, Great Britain got .uk, Germany got .de, Japan got .jp -- and Tuvalu got .tv, the most recognizable two-letter abbreviation in the world.(37)

Not long after that, entrepreneurs came up with the idea adding .tv as a new Internet suffix, to identify websites that have to do with TV programs or video games, instead of the more common .com, .org, etc. In 1998 Tuvalu sold its rights to the country code in return for $50 million, payable over a twelve-year period. The country’s gross domestic product immediately jumped by 50 percent. With the new revenue, the government could pave the only road on the main island, Funafuti; set up street lights; make electricity available to the outer islands; give college scholarships to promising students; and pay the $100,000 fee needed for a seat at the UN.

The Tuvaluans have used their membership in the United Nations and other international organizations to warn the world of the dangers posed by climate change. Arrangements have also been made to evacuate the country’s entire population to New Zealand, should their worst fears come true.

Nauru: The Island That Lost its Future

Nauru is a special case, that deserves to be told in detail. Huge phosphate deposits were discovered on Nauru at the beginning of the twentieth century, and after that they were heavily mined, first by the Germans, and later by the Australians.(38) In 1970, Nauru gained control over the Nauru Phosphate Corporation, and then the profits going to the native population really got huge. Most of it was deposited into the Nauru Phosphate Royalities Trust, a trust fund that would be used for investments, that would bring an income after the phosphates ran out. During the peak years of the mining industry, the 1970s and 1980s, Nauru had one of the highest per capita incomes of any nation (only oil-rich Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates claimed higher incomes), because the profits were shared with a tiny population, that never exceeded 7,500 in the twentieth century.(39)

Nauru started off with a strong president, Hammer DeRoburt, who dominated the government for most of the first twenty-one years after independence (1968-89). More recent governments tended to be weak and short-lived. Among the lesser politicians, the most important was Bernard Dowiyogo, who served as president seven times between 1976 and 2003. Because a multiparty political system is not feasible for a nation as small as Nauru, more than one government has held onto power with a one-vote majority.

Meanwhile, strip-mining activities turned most of the island into a bare, rugged, stony wasteland, stripped of vegetation and useless for any human activity. Even the climate was altered by the mining; the rocks reflected heat that repelled rain clouds from the island, causing droughts. In 1989 Nauru sued Australia in the International Court of Justice to receive compensation for the environmental damage caused by the mining. Four years later Australia and Nauru settled out of court, for $73 million, paid over a twenty-year period; the UK and New Zealand settled their involvement with one-time payments of $8.2 million each.

By the early 1990s, the end was in sight for the phosphate deposits, and orders were given to invest the trust fund money, now estimated at between $500 million and $1 billion. Most of the investments were either in real estate, like two high-rise buildings in Honolulu, Hawaii, or in various financial schemes. Foreign conmen got involved, and they persuaded Nauruans to put their money in places where it was quickly lost. The most notorious example was $2 million spent on a musical about Leonardo da Vinci, which played for only four weeks in London. Coincidentally, the script for that flop was written by the Australian financial advisor who recommended it (Andrew Lloyd Webber he wasn’t!). The government was persuaded to build an international airline it didn’t need, Air Nauru, which at its height had a fleet of seven planes, capable of carrying one tenth of the island’s population. You can probably guess that those planes flew empty much of the time, and the airline lost money constantly.(40) As for the foreign property, much of it languished undeveloped for decades, because Nauru could not afford the improvements that had been promised.

At the same time, ordinary Nauruans lived high off the hog. They paid no taxes, and got free schooling, healthcare, electricity, telephone service and housing. If they wanted to go to college or had an illness that the two local hospitals couldn’t handle, they flew to Australia for those services, and the government paid for their airplane tickets. Phosphate mining was outsourced to foreign workers; the only natives who had jobs were those hired by the government.

That last statistic included farmers. When phosphate mining intruded on native farms, Nauruans simply quit farming; it didn’t seem like a big loss, so long as they could import their food. Whereas their ancestors, like most Pacific islanders, had lived on fish, coconuts and root vegetables like taro, Nauruans now lived on canned and frozen food and drinks, especially Spam and beer.(41) If you know anything about nutrition, I don’t have to tell you that a diet made up exclusively of processed food is unhealthy, because of the chemicals added to preserve the food, or improve the appearance and taste. Worst of all, the sugar, sodium and fat levels in such food products are way too high. The availability of processed food all over the Pacific means that seven Pacific island nations have the world’s highest rates of obesity, diabetes, and heart disease, and Nauru tops the list – today’s Nauruans are literally the fat of the land. The result is that life expectancies in the South Pacific have fallen to some of the lowest in the world; e.g., nowadays Nauruan men are only likely to live to the age of 50, and women to 55.

Here in 2014, a group of Nauruans got some exercise and raised money for diabetes research by walking around the island’s airport. From Wikimedia Commons.

The combination of falling phosphate production, crazy spending, risky investments and outright fraud drained the trust fund to the point that Nauru was on the verge of bankruptcy in the late 1990s. Some new phosphate deposits were discovered in 2005, and new mining techniques allowed previously worked-out areas to start producing again, but it was clear that the phosphate industry would not generate profits like it used to. What’s more, most of the people had no useful skills, because they had not worked a day in their lives. In 1998 the government got a $5 million loan from the Asian Development Bank to pay the salaries of its employees – and the terms of the loan included firing a third of those employees a year later. After that, Nauru came up with creative ways to make money. Since there were still fish in the surrounding waters, Nauru made a little money by issuing fishing licenses. Then it indulged in a practice that had worked for some Caribbean nations -- offshore banking. For a few years, until the United States demanded an end to the practice, you could set up a bank in Nauru by simply paying a $25,000 fee; you didn’t have to visit the island, and the “bank” was nothing more than a post office box. Foreigners, especially Russians, used Nauruan bank accounts for money laundering, and Nauru recognized Abkhazia and South Ossetia, the two territories Russia took from Georgia in 2008, as sovereign nations in return for a $50 million pledge from Russia. In 2002 Nauru broke diplomatic relations with Taiwan, the only nation with an embassy on the island, when China reportedly pledged $130 million, and then switched back to recognizing Taiwan in 2005 when the Taiwanese offered enough cash. This opportunistic behavior prompted a Chinese official to grumble that Nauruans are “only interested in material gains.”

As the twenty-first century began, Nauru found a new role to play – as an Australian detention center. In 2001 an unseaworthy fishing boat, carrying 438 political refugees (most of them from Afghanistan), drifted and started to sink in the Indian Ocean, between Java and Christmas Island. A Norwegian freighter, the MV Tampa, rescued everyone aboard, and tried taking them to Christmas Island, because the island is Australian territory and the refugees wanted to go to Australia, but the Australian government, then under John Howard, refused to let the ship into any Australian port. After a big political debate, the government came up with the “Pacific Solution”: any refugee trying to come to Australia by boat would first have to go to Christmas Island, Nauru, or Manus Island (an island owned by Papua New Guinea, see footnote #47), and stay there until the Australian authorities decided what to do with them. Nauru received 30 million Australian dollars as its first payment for cooperating in this affair, and it also began restricting the number of foreigners allowed to visit the island; they especially won’t allow any journalists in, if they intend to interview the refugees.(42)

After that, Nauru held as many as 1,000 boat people seeking to enter Australia. Initially Canberra promised they would all be gone by May 2002, but refugees remained on the island for all of the Howard years. Living conditions in the detention center were condemned by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, and there was a hunger strike among the refugees in early 2004; neither speeded up the processing of the refugees. The detention center was closed by Kevin Rudd when he became prime minister in 2007, but it was reopened by Julia Gillard in 2012. This time around, Canberra dragged its feet forever on the processing of the refugees, acting like the old White Australia Policy was still alive; at one point it even proposed resettling them in Cambodia. At the time of this writing, the second detention program has spent more than $40 million, and it only accepted one refugee into Australia, a Rohingyan (Burmese Moslem) man. If this is a deliberate government policy to discourage refugees from going in Australia’s direction, it is succeeding; the few hundred refugees Australia has to deal with at any given time are a trickle, compared with the millions of refugees that have tried going to Europe and North America in recent years.

Of course Nauru doesn’t want any of the refugees to live there permanently, and the refugees don’t want to stay, as they see Nauru’s infrastructure running down. Supplies of fuel oil and gasoline are always low, and electricity and water have to be rationed when either the power plant or desalination plant run out of fuel. Employment in the private sector is practically nonexistent, with businesses limited to a few shops; for foreigners, the hotels, restaurants and rental cars are minimal.

The first European to see Nauru, a British naval captain named John Fearn, visited in 1798 and named the place Pleasant Island, because the natives he met were friendly. Nowadays that name seems like a cruel joke. The Nauruans are a sick people, both physically and spiritually. They have forgotten many of their traditions, and a recovery of their society would probably start with re-learning them. Their country is dependent on money and skilled labor from Australia and New Zealand; to keep afloat, they are stuck with being a client state of the Australians. The government still looks for money, to pay its workers and maintain a welfare state for its citizens. The desperation of the islanders shows in that they have resumed discussing what they were planning to do in the twentieth century – they want to buy an island, move to it, and start over again. But after what happened to the Nauruans’ first home, who in his right mind is going to let them get their hands on another island?

Papua New Guinea: A Troubled Young Nation

Some outsiders had a bad feeling about turning Papua New Guinea loose, as a nation that united the eastern half of New Guinea with the Bismarck Archipelago(43), plus Bougainville from the Solomon Islands. There were fears that fighting would break out between the different tribes and island communities, and that the military might stage a coup. In addition, an attempt by Bougainville to secede on September 1, 1975, fifteen days before independence, suggested that more breakaway movements could emerge.(44) Bougainville tried to declare itself a separate state, the Republic of North Solomons. The new PNG government retaliated by suspending the provincial government and withholding payments to the province. No nation recognized the separatist state, and an attempt to join the other Solomon Islands was rejected, so in early 1976, Bouganville accepted that it was part of Papua New Guinea -- for now.

Aside from Bougainville’s bid for independence, none of the fears expressed above became a reality for more than a decade. In the first elections after independence (1977), Michael Somare won another term as prime minister, but then in 1980 his government lost a no-confidence vote. Somare’s party, the Pangu Pati, continued to lead the ruling coalition, but it had a new cabinet and a new prime minister, Sir Julius Chan. The 1982 elections saw another Pangu victory, and Somare returned to power, but this time he could not complete his term, either; a second no-confidence vote brought him down in 1985, and Paias Wingti from the People’s Democratic Movement became the third prime minister, leading a five-party coalition. Wingti’s coalition narrowly won the next election, in 1987, and then in 1988 it was toppled by the latest no-confidence vote. A month before that vote, Rabbie Namaliu had replaced Somare as the Pangu leader, so Namaliu was the next prime minister.

By now Papua New Guinea had a reputation for unstable government, because the prime ministers, political parties and coalitions rose and fell so quickly and so predictably. One reaction to that was the introduction of legislation that makes new governments immune to no-confidence motions for their first eighteen months in office.

1989 was the year when the proverbial stuff hit the fan. What touched it off was the fact that New Guinea and Bougainville are rich in minerals, especially copper and gold, so large scale mines began opening in the 1970s, and they became Papua New Guinea’s largest income producers. A group named the Bouganville Revolutionary Army (BRA), launched a revolt in 1989, the goal being to gain independence for Bouganville. The rebels had two grievances, both connected with the Panguna copper mine; it was polluting the land and water around it, and most of the profits from the mine went not to Bougainvilleans, but to workers from New Guinea, and the mine’s Australian owners.

The first casualty of the Bougainville Civil War was the copper mine, which was closed, a move that caused Papua New Guinea to lose 40 percent of its GDP, and ruined the economy of Bougainville. The PNG government slapped a blockade on the island, using patrol boats and helicopters to enforce it. And that wasn’t all; the breakdown of law & order on Bougainville caused dozens of minor tribal conflicts, and relations with the Solomon Islands took a turn for the worse, as PNG forces launched unauthorized raids into the Solomon Islands to catch escaped BRA members. PNG forces captured Arawa, Bouganville’s capital, in February 1993, but the island’s jungle hindered their effectiveness elsewhere, and when they went for the copper mine, they failed to hold onto it. Likewise a cease-fire negotiated with moderate BRA leaders in 1994 was not accepted by all rebels, and Theodore Miriung, the leader of the transitional government set up for Bougainville, was assassinated in 1996.

Up to this point, government forces had never controlled more than 40 percent of Bougainville, and discipline and morale among them was unraveling. Sir Julius Chan, who had replaced Wingti as prime minister in 1994, tried something different -- at the beginning of 1997 he hired mercenaries from Sandline International, a London-based company that employed British, South African and Australian soldiers of fortune. But before the mercenaries saw any action, the Australian press heard they were coming. From that came a wave of international condemnation; the commander of the PNG armed forces ordered the detention of the mercenaries when they arrived; widespread protests, involving both civilians and military personnel, took place in Port Moresby; Australia intercepted the helicopters and other heavy equipment being shipped for the mercenaries’ use. Because of all that opposition, Chan cancelled the contract with Sandline, and subsequently resigned.

The one good thing about the Sandline affair was that it got the outside world involved in settling a conflict that had been ignored previously. New Zealand and the Solomon Islands hosted peace talks, leading to a truce in October 1997 and a permanent cease-fire in April 1998. A multinational truce monitoring group, led by Australia and New Zealand, watched to make sure the peace was kept, and to help fight crime, which was now growing in epidemic proportions. Finally, the Bouganville Peace Agreement was signed in August 2001; this promised a referendum on Bougainville’s future by 2020.(45) Estimates of the number killed in the civil war have reached as high as 20,000, most of them civilians. This was the biggest conflict the South Pacific had seen since World War II, with the possible exception of the fighting between Indonesians and Papuans in West New Guinea.

Sir Michael Somare, the country’s “father of independence,” returned in 2002 to serve as prime minister for the third time. He introduced electoral reforms to create a more stable political climate, and thus became the first prime minister to avoid those all-too-common no-confidence motions; then he was re-elected in 2007.

However, not all was well in Papua New Guinea. This was most obvious in the capital. Whole neighborhoods of Port Moresby had fallen under the control of raskols (pidgin English for “rascals”), criminal gangs that robbed or killed people, stole cars, and robbed banks and businesses. In other words, the streets of Port Moresby had become a real-life version of "Grand Theft Auto." Once, the raskols even used a stolen helicopter for an unsuccessful bank heist. And with a 70 percent unemployment rate, for many people in Port Moresby, joining a gang was the only way to make a living. The police cannot deal with the gangs because they are understaffed and underpaid; often they only enter raskol-controlled areas to confiscate food or cash.(46) In August 2004 Australia contributed police officers to help the beleaguered Port Moresby police, but the PNG Supreme Court ruled their deployment unconstitutional, so nine months later the Australian police went home.

The above episode did not strain relations with the mother country, but it was soon followed by another episode that did. In March 2005 Somare flew to Australia, and in the Brisbane airport, he was forced to remove his shoes and submit to a security check, though everyone knew the prime minster was not a terrorist. The PNG government demanded an apology, which Australia did not give. Relations did not improve again until 2007, when Kevin Rudd succeeded John Howard as Australia’s prime minister.

Somare’s good luck ran out in December 2010, when his prime ministership was suspended over charges of misconduct stretching back as much as twenty years. He resumed his term in office a month later, but then in April 2011 he went to a hospital in Singapore for heart surgery and remained in intensive care until June, when his family announced his retirement. While he was abroad, two acting prime ministers, Sam Abal and Peter O’Neill, served in his place. However, Somare returned in September and announced that he was still prime minister, because he had never wanted to step down. O’Neill insisted on staying, the governor-general ruled in favor of O’Neill, and in January 2012 an attempted mutiny by pro-Somare soldiers was nipped in the bud.

Papua New Guinea now effectively had two prime ministers, and both Somare and O’Neill decided to let the next Parliamentary election, scheduled for June 2012, decide who was in charge. Because the stakes and the threat of violence were high, Australia and New Zealand sent peacekeeping troops shortly before the voting began, just in case. The People’s National Congress Party, O’Neill’s party, won a plurality of the seats (27 out of 111), while Somare’s National Alliance Party came in fourth place, by winning 7 seats. After a month of voting and vote-counting, Somare conceded defeat, and O’Neill was sworn in as the ninth (and current) prime minister in August 2012.

Papua New Guinea has been politically stable since the 2012 election, but there are still the problems of high crime, corruption, poverty, poor education, and a failing health care system. Though the country is now forty years old, with great resources and a young and growing population, the overall socio-economic trends for the near future do not look good. Now that a new generation of leaders has taken charge, they will have to work together, and with friendly partners like Australia(47), to reverse the downward trends. In all likelihood they will have to tackle one or two problems at a time, rather than take on all at once.

Samoa: No Longer Western, But Looking Southwest

For the first twenty years after independence, Western Samoa had no political parties; in their elections, personalities and issues were all that mattered. Only the chiefs voted; the prime minister was elected by Parliament; all cabinet members had to be members of Parliament first. Because the chiefs had learned to cooperate when they weren’t competing, this system was a very stable one. The constitution adopted in 1960 is still in effect today, and before 1982, Samoa had only four prime ministers.

In the 1982 election, the first political party appeared, called the Human Rights Protection Party. The prime minister elected that year, Va’ai Kolone, had to resign after five months when he was charged with bribery. The previous prime minister, Tupua Tamasese Tupuola Tufuga Efi (Tufuga Efi for short), returned to office in order to fill the vacancy, but three months later (December 1982) new elections were held and he was defeated. Since 1982 there have been three prime ministers, all from the Human Rights Protection Party; the current prime minister, Tuilaepa Aiono Sailele Malielegaoi, was elected in 1998. In 1990, a referendum on universal sufferage passed with 51% support, so now all Samoans 21 years old or older may vote.

Another amendment, passed in 1997, dropped the adjective “Western” from Samoa’s name, and the official name became “Independent State of Samoa.” This caused American Samoa to make a big fuss; folks in Pago Pago asked if this meant there was only one Samoa, and if so, what were the American Samoans? Two legislators from American Samoa went to Apia, in an effort to get the name change reversed; American Samoa sent a petition to the United Nations to have the new name banned; and the American Samoan legislature considered a bill that tried to keep American Samoa from recognizing the new name. All of those measures failed, and Independent Samoa kept the name it wanted; cooler heads prevailed in the end.

Susuga Malietoa Tanumafili II, Samoa’s senior chief and head of state, died in 2007 at the age of 95. Tupua Tamasese Tupuola Tufuga Efi, the former prime minister, was elected by the legislature as the next head of state, because he also happened to be the son of Tupua Tamasese Mea'ole, a previous top-ranked chief. Tufuga Efi still holds that title now.

In foreign policy, Samoa remains hitched to the mother country, New Zealand. Helen Clark, the New Zealand prime minister, visited in 2002 to formally apologize for the mistakes New Zealand made in the early twentieth century, especially letting a ship dock in Apia that carried the Spanish flu, and the heavyhanded suppression of a nationalist demonstration in 1929 (see Chapter 4). In September 2009, Samoa made its drivers switch to driving on the left side of the road, because Australia and New Zealand drive on the left side of the road, too. Unfortunately, the same month saw a tsunami strike that part of the Pacific, killing 148 in Samoa, 34 in American Samoa and nine in Tonga. Finally, New Zealand has become the primary destination for Samoans traveling abroad, for both jobs and tourism, so a community of 131,000 Samoans now lives in New Zealand.(48)

In 2011 Samoa and Tokelau both decided they wanted to be in the UTC+13 time zone (see the second Kiribati section), so that instead of setting their clocks twenty-three hours behind the clocks of New Zealand, they would be just one hour ahead. They made the shift at midnight on December 29, by having their calendars go directly to December 31, skipping December 30. However, American Samoa is still in UTC-11, because of its ties to the United States. Thus, the International Date Line now runs between the two Samoas, and if they are ever reunited, something will have to be done about that.(49)

The Solomon Islands: Are They A Nation Yet?

The last time we looked at the Solomon Islands, we noted that its inhabitants had trouble seeing themselves as a nation. For most of them, Wantok, an association of people of the same language or family group, was the community that mattered the most. This was in keeping with the Melanesian tendency towards division and diversity, that we have noted since Chapter 1. While they might support a movement to make their home island a unified, independent nation, government on any level above that was undesirable, because it meant they would have to pay taxes to an organization that gave back little in return.

For the first nineteen years after independence, the government ran reasonably well; two political parties and four prime ministers took turns running the show. Even when the fighting between Bougainville and Papua New Guinea spilled over into the islands in the early 1990s, damage was minimal. However, trouble did appear on the horizon after the election of the fifth prime minister, Bartholomew Ulufa’alu, in 1997. Initially, the problems looked mainly economic: high debts, too much government spending, and loggers cutting down trees at an unsustainable rate. Ulufa’alu’s attempts to deal with these problems and reduce corruption led to three no-confidence motions, the last of which he only won because the votes were tied. But ethnic tensions soon proved to be even worse. The main hotspot was the capital, Honiara; though it was located on Guadalcanal (see Chapter 4, footnote #26), most of its residents came from other islands, especially Malaita.

Those tensions led to outbreaks of violence in late 1998. Natives of Guadalcanal, the Gwale tribe, formed a militant group that went by two names, the Guadalcanal Revolutionary Army and the Isatabu Freedom Movement (IFM). They began attacking Malaitans in rural parts of Guadalcanal, and the Malaitans either fled to their home island or they took refuge in the capital, where they in turn kicked out the Gwale living in Honiara. Before long the Malaitans had a force of their own to defend themselves, the Malaita Eagle Force (MEF).

The feuding tribes called on the Commonwealth Secretary General to help resolve this dispute. With the help of Sitiveni Rabuka, the former prime minister of Fiji, a cease-fire agreement was introduced, and approved on June 28, 1999. But by now more than a hundred had been killed and at least 20,000 refugees (mostly Malaitans) had been displaced, so it was going to be hard for the natives to forgive and forget. The cease-fire lasted for eleven months.

On June 5, 2000, armed members of the MEF seized Parliament by force, claimed that Prime Minister Ulufa’alu had not done enough to compensate the Malaitans for what they had lost, and forced him to resign. At the end of the month, a quorum of Parliament members met on an Australian warship and they voted 23-21 to elect Manasseh Sogavare, a former finance minister, as the next prime minister.

The Australian government encouraged the government and the armed factions to sign a peace agreement in Townsville, Australia, in October 2000. This called for granting amnesty to all militia members who surrendered their arms by a certain deadline, and a program of economic development for the island of Malaita. Former militia members were to do most of the arms collecting, supervised by unarmed peacekeeping troops from Australia and New Zealand. Another peace agreement was signed in February 2001, but life did not get better; the economy deteriorated and sporadic outbreaks of violence continued. The government could not provide services or public safety, civil servants were rarely paid, and cabinet meetings had to be held in secret to prevent local warlords from interfering. Many weapons remained in the hands of the militias, and the police were unable to restore law and order because many of them were also militia members. In August 2002, Father Augustine Geve, a Catholic priest and cabinet member, was shot dead by Harold Keke, the IFM leader.

By mid-2003 the situation was so bad that the prime minister called for outside help, and Parliament voted unanimously in favor of it. An Australian-led force of 2,200 soldiers and police from all other South Pacific nations was assembled, and called the Regional Assistance Mission to the Solomon Islands (RAMSI).(50) Harold Keke surrendered to them in August 2003, and was subsequently sentenced to life in prison, along with two associates who were with him at the above murder.

The main tasks of RAMSI were to disarm the militias, and expel the “thieves, drunkards, and extortionists” from the notoriously corrupt police force. Their intervention was successful enough that some of the troops were able to return home at the end of 2003, though enmity between the two ethnic groups persisted. The best way to heal bad feelings was to heal the economy, so Japan, New Zealand, Australia, and the European Union sent foreign aid to help the country get back on its feet.

After the 2006 election, another round of rioting and looting broke out, this time directed at the Chinatown neighborhood in Honiara, because the new prime minister, Snyder Rini, was seen as too willing to make concessions to China. Eight days after taking office, Rini stepped down. Parliament then elected the opposition candidate, Manasseh Sogavare, to fill the post for a second time. However, a controversy soon broke out over Sogavare’s appointment to the post of attorney general. That candidate, Julian Moti, also happened to be an Australian citizen, and was wanted in Australia on child sex charges. Moti fled to Papua New Guinea, was arrested and brought back to the Solomon Islands, released on bail, and eventually extradited to Australia, where in 2011 all charges were dropped, because having Australians carry out his extradition violated Solomon Islands law. Sogavare threatened to expel the multinational force because of this affair. However, RAMSI still maintains a presense in the islands today, helping to build a modern and effective police force, though the military phase of its mission ended in 2013.

An aerial picture of burning buildings in Honiara’s Chinatown, during the 2006 riots. Source: Britannica.com.

Sogavare’s second term ended when he lost a no-confidence vote in December 2007. Three more prime ministers came and went over the next seven years, and then a secret ballot by members of Parliament elected Sogavare to a third term in December 2014.

Constitutional reform is a current activity of the government. In 2009 a national truth and reconciliation commission, like the one South Africa had in the 1990s, was launched to investigate the Guadalcanal conflict of 1997-2003. There is also talk about a possible new constitution, that will defuse provincial and ethnic tensions by establishing a federation of states, rather than a centralized government.

Besides the turmoil mentioned above, the Solomon Islands have suffered from multiple natural disasters: earthquakes and the resulting tsunamis (2007, 2010, and 2013), flooding from heavy rains (2009), and Tropical Cyclone Ita (2014). Other challenges come from the economy, deforestation, and malaria. While conditions are improving at the time of this writing, the political situation remains unstable, so we’ll have to end this section with the Solomon Islands facing an uncertain future.

Tonga: It’s Good to Be King

Because Queen Sālote Tupou III ruled Tonga for all of her adult life, her son, Tāufaʻāhau Tupou IV, was already forty-seven years old when he inherited the throne in 1965. He managed to rule nearly as long (1965-2006), but aside from the termination of the British protectorate that we mentioned previously, his reign wasn’t as successful as his mother’s. Whereas Queen Sālote’s top priority had been the preservation of Tongan culture, Tupou IV felt that modernizing the country was more important, so the first things he did were to build the International Dateline Hotel, and upgrade Fua'amotu Airport to handle jet aircraft. You will remember from Chapter 4 that Queen Sālote had opposed the building of hotels while she was alive, but now both the hotel and airport were ready in time to handle the foreigners that came for his coronation(51) in 1967, and afterwards they handled Tonga’s new tourism industry. The new king also had an interest in improving education, so he built schools and wrote rules to standardize spelling in the Tongan language.

One of the undeniable truths of history is that no man has ever built a perfect society, but that doesn’t stop people from trying it. For this example, the would-be Utopia maker was an American millionaire, Michael J. Oliver, who dreamed of founding a micronation that followed Libertarian principles. The site he picked for the project was the Minerva Reefs, some coral reefs 250 miles south of Tonga, named after the Minerva, an Australian whaling ship that ran aground there in 1829. This micronation would have “no taxation, no welfare, no subsidies, or any form of economic interventionism.” It would be supported by the registration of cargo ships, fishing, tourism, light industry and any other commercial activities the leaders could think of (offshore banking, perhaps). In December 1971 some barges full of sand sailed from Australia and dumped enough sand on the reef to create two artificial islands; then a small steel tower was built, which doubled as a radar reflector and a flagpole. Four weeks later, on January 19, 1972, Oliver issued a declaration of independence for the “Republic of Minerva,” and began minting Minervan coins. Morris C. “Bud” Davis was elected as the first (and only) president.

Overtures were sent to the outside world, but no nation recognized the Republic of Minerva. In fact, the only nation that reacted was Tonga. The Minerva reefs had been a Tongan fishing ground in the past, so King Tufou IV wasn’t going to take this lying down. In June 1972 he issued a formal claim to the reefs, and in September he sent an expedition to take the Minervan isles. A yacht sailed to the disputed area with the king, his retinue, and an assortment of soldiers and policemen. The people they met on the islands were unarmed, and surrendered without a fight. While the king stayed in the boat, the enforcers he brought took down the flag (the Minervan flag had a yellow torch on a dark blue field), raised a Tongan flag in its place, and with the mission accomplished, the expedition went home.(52)

Ex-president Bud Davis came back in 1982 to claim the Minerva Reefs again, but his second “presidency” was shorter-lived than the first; another boatload of armed Tongans chased him away, three weeks later. Since then a few others have disputed Tonga’s claim to the reefs, but the only one doing anything about it is the government of Fiji, which has issued its own claim and sent a few patrol boats to the reef since 2005. But if anyone wants to build a new nation in the reefs, they will have to start from scratch; waves from the ocean have washed away the artificial islands by now.

A pro-democracy movement, made up of commoners who felt the king should not be an absolute monarch, got started in the late 1980s, with the founding of Kele'a, a newspaper that revealed government corruption almost from the first issue, starting with the discovery that government ministers were spending too much on trips abroad. But as scandals go, that was routine; much worse was to come.

Like the governments of the other small Pacific island nations, the king of Tonga tried various forms of fundraising to increase the small amount of revenue that came from the usual resources. Selling passports helped, but this raised a few eyebrows when the passports cost as much as $26,000 each, and four passports were reportedly sold to the exiled family of former Filipino President Ferdinand Marcos. It also led to the creation of a Chinese community in Tonga, made up of folks from Hong Kong who didn’t want to stay in that colony when the British handed it over to China in 1997. Another moneymaker was allowing foreign ships to register as Tongan, and that embarrassed the country when an Al Qaeda terrorist cell was caught using one of the ships to smuggle weapons into Europe. Strangest of all was Tonga’s attempt to claim and sell the sixteen most desirable places in geosynchronous orbit that didn’t have communications satellites yet. What made this odd was the fact that Tonga lacked a space program, and you wouldn’t expect a country that only had 4,000 telephones (enough for about 4% of the population) to have much interest in telecommunications. When others disputed the Tongan claim, the International Frequency Regulation Board ruled that Tonga could only have six of the sixteen unused satellite “parking spots.”

The fortune that Tupou IV raised through the above schemes was sent directly to a checking account in the United States, managed by Bank of America; the king said that if the money stayed in Tonga, “the government would only spend it on roads.” There the money sat until it was discovered by a bank employee, Jesse Dean Bogdonoff, who contacted the king and offered to help him invest the money in places where it would draw a higher rate of return. The king was delighted and when Bogdonoff quit the bank in 1999, the king gave him a royal title so he could keep handling the country’s trust fund legally -- the king made Bogdonoff the court jester.

Bogdonoff moved most of $26 million into Millennium Asset Management, a brand-new Nevada-based life insurance company, and the owner of that company did not pay the returns he promised. The rest of the funds were invested in two companies that promptly went belly-up. For a government that spent $40 million a year, losing $26 million was a terrible shock; subsequent attempts to recover the money only got back $2 million. The resulting debate between the royal family and pro-democracy activists paralyzed the government, and forced Tonga’s deputy prime minister and education minister to resign. Bogdanoff fled the country in 2004 when the government sued him; later he worked out a settlement where he only had to pay a fraction of the money lost. Since then he has worked as a hypnotherapist in California and composed the music for a jazz CD. Joseph Silovsky, a New York writer who heard about the affair, wrote a play about both Bogdanoff and Michael Oliver, calling it “The Jester of Tonga.” In case you are wondering, I did not make up anything you are reading in this section.

While all of the above events were happening, the king surprised his subjects in a good way. In the 1970s he weighed as much as 460 pounds, making him the world’s heaviest monarch. This was a native tradition; Tongans expected their ruler to be the largest person among them. However, this meant he had trouble getting around, and special arrangements had to be made for his ample, six-foot-four-inch frame, whenever he traveled. What’s more, he expressed a desire to live as long as his great-grandfather, George Tupou I (see Chapter 3). Readers will know by now that long lifespans are in the genes of the Tongan royal family, but Tupou IV wasn’t likely to get his wish while lugging that much weight around, so during the 1990s he went on a diet where he often ate nothing but three yams a day. By 1998, he had shed more than a third of his body weight, slimming down to 286 pounds. Even so, he only lived to the age of 88, seven years less than Tupou I.

King Tupou IV’s last years were not happy ones. In 2002 his opponents made another scandalous discovery; the king personally owned $350 million in other foreign bank accounts. Of course that money would have gone a long way towards giving Tonga the infrastructure improvements it needed, and when asked about it, all the king said was that he had earned the money from his vanilla farm. Well, only the nation of Madagascar should have that much vanilla. Then in 2005, Tonga’s civil servants went on strike for six weeks, until the government agreed to give them a pay raise, and in 2006, the year of the king’s death, a pro-democracy gathering turned into a riot which burned down several buildings in Nuku'alofa, the capital.

The next king, George Tupou V, was sixty years old when he succeeded his father. Before becoming king, he announced he was in favor of making Tonga more democratic, and after being crowned he promised to give up most of his powers, especially the right to appoint the prime minister and Parliament members. A new electoral law was passed in May 2010, and the following November saw Tonga’s first free election. While this sounds like progress, it was all the king got done; he died of leukemia in March 2012, after ruling for only five and a half years. Because the king was a bachelor with no legitimate children, his younger brother, ʻAhoʻeitu ʻUnuakiʻotonga Tukuʻaho Tupou, took over, becoming King Tupou VI. So far the main event of Tupou VI’s reign has been a second free election, held in November 2014.

Vanuatu: Harmony With Disunity

Like the other Melanesians states (Fiji, Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands), Vanuatu has found it a challenge to run a stable government. In Vanuatu’s case, the root cause of disunity is the fact that it was run by two colonial powers, not one, before indpendence. The country’s legal system draws its ideas from both British common law and French civil law, while the political factions will either be pro-British and English-speaking, or pro-France and French speaking. The result is that in the thirty-six years from independence until the time of this writing (October 2016), there have been twenty-two changes of prime ministers, and even more changes of government, most of them coalitions. The coalitions are not stable either, with parties and MPs regularly "crossing the floor"; prime ministers are far more likely to be ousted in no-confidence motions than they are to complete their terms.

The first eleven years were the most stable. The Vanua’aku Pati, Father Walter Lini’s political party, won a majority for three elections in a row, so he was prime minister during that time. Lini and the VP followed a neutral foreign policy, seeking good relations with both capitalist and communist countries. Then in September 1991, after no-confidence votes, Donald Kalpokas replaced Lini as both VP party leader and prime minister. But then in the election three months later, the pro-French Union of Moderate Parties (UMP) formed a coalition, and a pro-French prime minister, Maxime Carlot Korman, took charge next. Surprisingly, that coalition included Lini and some VP members who opposed him being forced out of office.

Carlot Korman led a string of coalition governments until the 1995 election, when the appearance of political harmony disappeared. The next six years saw coalitions that could not last (at least two were accused of corruption and criminal activity) and six prime minister changes, which included brief second terms for Kalpokas and Carlot Korman. Fortunately, the frequent changes of those in charge was accomplished without violence, making Vanuatu a more attractive place for foreign investment than other Melanesian countries.(53)

The situation became somewhat less chaotic when Edward Natapei of the VP became prime minister; he remained in office from 2001 to 2004. Natapei would later serve a second time, from 2008 to 2010, and for a few days in 2011. The only other prime ministers to serve for more than a year were Ham Lini (2004-2008), and Sato Kilman (2010-2011, 2011-2013 and 2015-2016). The prime minister since February 2016, Charlot Salwai, comes from a party called the Reunification of Movements for Change, and in the preceding election, that party won just 3.44% of the vote and three of the fifty-two seats in Parliament, showing how splintered Vanuatuan politics can be.

As with Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu has fallen victim to natural disasters more than once since independence. We mentioned the country’s volcanoes previously (see footnote #20), and Port Vila was badly damaged by an earthquake in 2002. But the worst disaster was probably Cyclone Pam, a tropical cyclone with wind speeds as high as 185 miles per hour, that swept across the archipelago in March 2015. Thanks to the availability of evacuation centers, the storm did not cause many deaths, but Vanuatu’s communications system and power grid, was virtually wiped out. Also hard hit by Pam were the Solomon Islands, Kiribati, Fiji, Tuvalu and Papua New Guinea, so when all is said and done, this may go down as the most widespread natural disaster in South Pacific history.

New Caledonia: Unfinished Business

As we saw previously, the Kanaks, New Caledonia’s native population, had several good reasons to be mad at Europeans, especially their French rulers: disease, the loss of their land, economic exploitation, indentured labor (“blackbirding”), and the temporary use of their island as a penal colony. The French have kept control since World War II by promising to address the grievances of the natives -- but not immediately -- and by changing their status more than once. New Caledonia was declared an overseas territory of France (a higher status than that of a colony) in 1946, and French citizenship was granted to all New Caledonians in 1953, no matter what ethnic group they came from. At least five more statutes affecting the natives were passed between 1976 and 1988. Nevertheless, supporters of independence tried to take matters into their own hands, and in 1984 the various Kanak independence movements formed an alliance, the Kanak and Socialist National Liberation Front (see footnote #11).

The worst incident involving the Kanak and Socialist National Liberation Front took place in April 1988, when it killed four French gendarmes, and kidnapped thirty-five French officials (twenty-seven gendarmes, a public prosecutor and seven soldiers) on Ouvéa, a nearby island. The hostages were held in a cave; twelve gendarmes were later released, and when negotiations over the others failed to reach an agreement, France sent soldiers on a rescue mission to Ouvéa. In the battle that followed, all of the hostages were freed, two soldiers were killed, and nineteen separatists were killed. Afterwards, a rumor went forth that some of the Kanak deaths were on-the-spot executions after the separatists surrendered, and that the leader of the kidnappers died because he did not receive medical treatment for a serious gunshot wound to the leg. If you want to learn more about this crisis, it was made into a movie, Rebellion, in 2011. As for the Kanak and Socialist National Liberation Front, it split into factions in the early 1990s, and that has kept it from winning local elections, or from being effective in any other way.

After the Ouvéa crisis, pro-French and pro-independence Kanaks took part in negotiations that led to the Matignon Accords in June 1988. This promised a ten-year period of transition, followed by a referendum on self-determination. Another agreement, the Nouméa Accord, was signed in May 1998, and when the promised referendum came, 72% of the voters approved the Nouméa Accord. This created a New Caledonian “citizenship,” and allowed self-government in everything except the justice system, public order, currency, defense and foreign affairs. Finally, it promised one more referendum on the independence issue, to be held no later than 2018. So far France has managed to keep some measure of control over New Caledonia by postponing the final vote, in effect, kicking the can down the road. We will find out in 2018 if the French can continue to do that any longer.

Conclusion for the Islands

We have come to the end of the line for this narrative, having reached the present. What are future prospects for the island nations of the Pacific? In the past, the leading Western nations (those in Europe) only paid attention to the Pacific as an afterthought, because it was so far away, largely unknown before the nineteenth century, and as we have noted before, underpopulated. Even during World War II, anyone who wasn’t in east Asia or the Pacific tended to see Europe as the war’s main theater, though Japan controlled more people and a larger portion of the globe’s surface than Germany did. Unfortunately, I expect that lack of attention will continue for at least the near future.

For the Micronesian nations (FMI, RMI, Palau, Kiribati, Tuvalu and Nauru), the biggest challenge will be to free themselves from the restraints imposed upon them by nature, economics and demographics, which have left them with so few opportunities. The Melanesian nations (Fiji, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu) have enough land, people and resources to do better, but they must overcome the tendency to stay divided, which has characterized Melanesians for as long as anyone can remember. That will include the two Melanesian-populated areas that are not independent at this time, western New Guinea and New Caledonia, should they find themselves on their own. Finally, the two Polynesian-run nations of Samoa and Tonga appear to be doing all right, but we need to keep in mind that most Polynesians, whether in the Marquesas or Society Islands, Easter Island or elsewhere, are still under non-Polynesian rule, so new chapters of the Polynesian story may be written in the future. And two of the largest Polynesian communities, in Hawaii and New Zealand, may never become independent, because they are now minorities in their homelands; their challenge will be to keep their identity in a modern world where intermixing and assimilation are the norm.

Worldwide, the trend seems to be that society is getting less violent as time goes on. Warfare is still a terrible business, but not as many people are killed by it as was the case in the past; moreover, in most of the world, there are fewer atrocities, executions, and other cases of man’s inhumanity to man. Several factors seem to be responsible for this. One is the overall tendency for modern man to be passionless, compared with his ancestors. Lately scientists have noted that men do not have as much testosterone as they used to, and when you combine that with fewer life-threatening challenges in today’s world, the result appears to have made us the wimpiest generation that ever lived. Another factor is the maturity of modern societies in general, and the fact that in recent years the standard of living as gotten better in many non-Western nations. Today the world has more democracies than ever, and democracies don’t make war on other democracies. Among the tyrannies of the twentieth century, fascism is dead, and except in North Korea, communism is a shadow of its former self. Only Islamic extremism remains from the past century, as a source of injustice and a threat to civilization as we know it.(54) What this means for the South Pacific is that we can expect future disputes will be easier to settle without resorting to violence. In that sense, the future should be more comfortable for mankind than the past -- and less exciting, especially for historians.