| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

The Anglo-American Adventure

Chapter 4: Industrial America, Part II

1861 to 1933

This paper is divided into five parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| America's Most Difficult Years | |

Part II

Part III

| The Panic of 1873, and the Barons of Wall Street | |

| The South Restored, and the Worst Happy Hunting Grounds | |

| The Great Railroad Strike | |

| The Spoils System Kills the President | |

| Grover the Good | |

| "I Will Fight No More Forever" | |

| The Great Barbecue | |

| The Gay Nineties |

Part IV

| The Spanish-American War | |

| Teddy and the Big Stick | |

| Big Taft and the Bull Moose | |

| Wilson the Reformer | |

| World War I | |

Part V

| The Age of Normalcy Begins | |

| The Roaring Twenties | |

| The Great Depression | |

| The Golden Age of Immigration |

The Western Theater, 1864

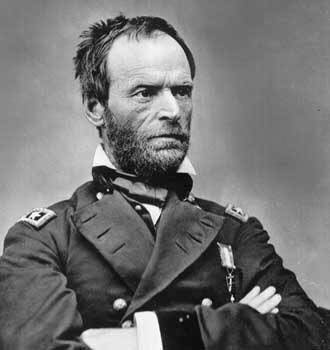

For the first four score and seven years of the nation's existence, only two men had held the rank of lieutenant general: George Washington and Winfield Scott. Congress revived that rank in March 1864, to give to the man who would be supreme commander of the Union Army on every front. And Lincoln knew who should get that job--Ulysses S. Grant. Not only had Grant won more battles than the other generals, he had used whatever men and materiel had been sent to him, without complaining, and at Shiloh and Vicksburg he showed he could learn from his mistakes. This also meant a promotion for William Tecumseh Sherman, who was moved up to the position Grant had most recently held, commander over the whole Western Theater.

General William Tecumseh Sherman.

For 1864, Grant's plan was to subdivide the South. While Meade continued to hammer away at Lee in Virginia, Sherman would lead the Army of the Cumberland from Chattanooga to Atlanta and beyond, and Nathaniel Banks would march from Louisiana to Mobile, AL. Banks did not play his part, though, because he had been given different orders before Grant's promotion, and by the time Grant found out, it was too late to stop him. Instead, Banks went in the opposite direction, going up the Red River toward Texas, backed by the fleet of Admiral Porter. They wanted to capture the stockpiles of cotton stored in that area, before the CSA could sell it to factories in Europe, and then secure Shreveport and conquer as much of Texas as possible. Furthermore, France had recently invaded Mexico, and there was concern that Napoleon III would cross over to this side of the Rio Grande and try giving the Confederacy some direct assistance.

The whole Red River Campaign was a fiasco; Grant was right when he felt it was an unnecessary distraction from the rest of the war effort.(24) Sherman contributed 10,000 of the 27,000 men used in the effort, men who would have been put to better use if he kept them for his own campaign. Another force of 15,000 was supposed to march south from Little Rock, but it got started late, was defeated in southern Arkansas by the cavalry of General Sterling Price, and forced back. Opposing them in Louisiana were 30,000 men led by Confederate General Richard Taylor, son of former president Zachary Taylor. The two land forces under Banks and the ships under Porter moved out on March 10; they were supposed to meet at Alexandria, LA, but coordination was so bad that they arrived on separate days. Upstream from Alexandria the river level was much lower than expected, severely slowing down Porter's fleet. At the end of March Banks reached Nachitoches, 65 miles south of Shreveport, and after a week of skirmishing, Taylor decided to make his stand there. The resulting battles at Sabine Cross Roads (April 8) and Pleasant Hill (April 9) were Confederate victories, and because Grant now wanted Sherman's troops back, Banks called off the campaign. Over the course of late April and May the Union troops and ships retreated the way they came. The Red River's level had dropped so low that the ships became targets for Confederate cannon and sharpshooters. At one point the river was only three feet deep, and the ships only got past there because Lt. Col. Joseph Bailey suggested building a dam to raise the water to the level needed for the fleet to continue. In the end the Union lost 8,162 men, nine ships (including three ironclads), 57 cannon and 822 wagons. They weren't even very successful at capturing the cotton; Southerners burned $60 million of it before it fell into Union hands, much of what they did capture had to be abandoned when the ships got stuck, and there were questions raised about what Banks did with the rest. Banks was never allowed to command an army again, and as for Mobile, Admiral Farragut sailed into Mobile Bay in August 1864, captured the two forts (Fort Gaines and Fort Morgan) guarding the bay's entrance, and defeated the Confederate squadron in the bay itself.(25)

Today on Interstate 75, it is 115 miles from Chattanooga to Atlanta. That doesn't sound like a great distance to the modern-day motorist, but for Sherman it was tough going. Not only was it rugged terrain, because he was coming out of the Appalachian mts., there was also a Confederate army blocking the way. Opposing Sherman's 112,000 veteran troops were 60,000 ill-equipped Confederates, led by Joseph E. Johnston, Bragg's successor. Sherman began moving in the first week of May, and by digging in at every good defensive spot, Johnston was able to slow him down considerably. Most of May and June saw continuous fighting, but no big battles or long casualty lists. Usually Sherman would get around Johnston with a flanking movement, Johnston would rush on ahead to stop Sherman again, and the cycle would repeat itself. On June 27, Sherman lost patience with these tactics and ordered three divisions to make a frontal assault on Johnston's entrenched position, at Kennesaw Mountain. It was the same mistake that Grant had just made at Cold Harbor (see the next section), with much the same results; Sherman lost more than 2,000 killed and wounded, compared with about 500 casualties on Johnston's side. After that, the cat-and-mouse game resumed until early July, when Johnston pulled back to the outskirts of Atlanta, and Sherman spread out his force to besiege the city from the northwest, west and southwest.

Johnston had accomplished much against the odds, but Jefferson Davis was not impressed. All he saw was that Sherman was about to take Atlanta, so in mid-July he replaced Johnston with a general known for reckless courage, John B. Hood (at 33 years of age, Hood was the youngest Confederate general). True to character, Hood rashly attacked Sherman on July 20, 22 and 28, being driven back with heavy casualties each time. Sherman responded by swinging south and cutting the rail line which brought in supplies for the defenders. This forced Hood to evacuate Atlanta on September 1, and Sherman triumphantly entered the city a day later.

The taking of Atlanta was important because it was one of the few industrial centers the South had, and because the battle probably saved Lincoln's presidency. The 1864 election was approaching fast, and in much of the North, the war had gotten very unpopular. Most of the news from the front lines for that year was bad, and while Grant had done better in Virginia than all his predecessors, he still had not destroyed Lee or taken Richmond; people talked instead about how there seemed to be no limit to the number of lives Grant was willing to sacrifice. For 1864 the Republicans invited the "War Democrats" to join them as the "National Union Party"; one of the Democrats who joined, former Senator Andrew Johnson of Tennessee, became Lincoln's running mate. The rest of the Democrats nominated General George McClellan, because a military man seemed like the right candidate to deliver a defeatist message. Lincoln himself came up with the best slogan for the campaign, "Don't swap horses when crossing a stream," but as late as August 23 he told the Cabinet it seemed "exceedingly probable" that he would not be reelected. Sherman's victory at Atlanta, followed by General Philip Sheridan's sweep through the Shenandoah Valley in October (see the next section), gave the Republicans the morale boost they needed. By November the mood of the voters had turned around; on Election Day Lincoln carried every Union state except Kentucky, Delaware and New Jersey, giving him a commanding 212 electoral votes to McClellan's 21.(26)

One week after the election, Sherman was ready to move again. What he did next is still one of the most controversial actions of the war. In a sense, like Grant, he was one of the first "modern generals." Southerners regard him as somewhat psychotic for the way he destroyed Southern property, but Sherman himself argued that if you hate war as much as he did, then you will agree that you should do what is needed to win quickly: "War is cruelty. There is no use trying to reform it. The crueler it is, the sooner it will be over."(27) Sherman's goal was to hit the South where it really hurt, and to do that, he would ignore Hood--who did not have enough troops left to stop him anyway--and go on without supply lines. After burning Atlanta, his force marched south to the outskirts of Macon, and then turned east to make Sherman's famous "March to the Sea." Many naysayers said the army wouldn't last without supplies, but the army spread out in several columns, covering an area forty to sixty miles wide, so it could live off the land effectively. Anything that the troops couldn't consume or take with them was destroyed, in a scorched-earth policy: railroads were torn up, bridges were blown up, houses of locals who did not cooperate were burned, slaves were freed, and even dogs were killed if they had been used to track escaped slaves. When they captured Milledgeville, the state capital at the time, they stopped just long enough to hold a mock session of the Georgia legislature.(28) For those who criticized Sherman's policy, he said, "If the people [of Georgia] raise a howl against my barbarity and cruelty, I will answer that war is war, and not popularity-seeking." Sherman himself estimated the cost of the total damage to Georgia at $100 million. On December 22 he reached Savannah, which he offered to Lincoln as a Christmas present, and a supply line to his army was reestablished by sea.

While Sherman was making Georgia "howl," Hood tried to cause trouble in the rear of Sherman's army, by staging a counterstrike into Tennessee. Sherman did not take the bait, but he did send back part of the army under General George Thomas to deal with Hood. They were able to keep Hood stuck in northern Alabama for most of October, unable to cross the Tennessee River, but in early November another Confederate General, Nathan Bedford Forrest, launched a raid from Corinth, MS that captured several Union steamers and a gunboat near Johnsonville, TN, and though Forrest had to abandon the vessels later, that distraction allowed Hood to break into Tennessee. After that Thomas slowed down Hood's advance again, but he could not stop it. On November 30, Hood, acting as impulsive as ever, ordered his troops to charge part of the Union Army that was trying to form a defensive position around the town of Franklin. To do this they would have to run across a mile of open fields without artillery support. For the Yankees it was like a turkey shoot; 6,000 Confederates were killed or wounded that day, including six generals and more than fifty colonels.

Although victorious, the local Union commander, General John Schofield, withdrew to Nashville, where Thomas was assembling the rest of the army. Hood followed, thinking that his army would break up completely if he admitted defeat, took up positions on the high ground just south of Nashville, and tried to besiege the city. How did that go? Not too good! Not only did Thomas now have a 3:2 advantage in numbers, but Hood made a capital mistake before the battle, by sending Forrest off with most of the cavalry to attack a Union garrison at Murfreesboro. For two days (December 15 & 16) Thomas delivered a series of heavy assaults on the Confederate force, using overwhelming power to shatter Hood's lines just about everywhere, resulting in "one of the most smashing victories of the war." This time even Hood couldn't keep the survivors on his side from fleeing southward; of the nearly 40,000 men he took into Tennessee, not quite 10,000 came out again. Many Confederates simply drifted back to their homes, feeling that the war was over for them. Hood retreated to Tupelo, MS and resigned his command; President Davis, learning his lesson the hard way, recalled Joseph E. Johnston and put him in charge of what was left.(29)

The Eastern Theater, 1864

The 1864 campaign in Virginia, like Sherman's campaign, began in the first week of May. Officially Meade was still commanding the Army of the Potomac (and would do so for the rest of the war), but Grant showed up at the outset and kept Meade on such a short leash that he was the one really in charge from now on. Grant's strategy was simple--no fancy maneuvers, just a war of attrition. He reasoned that the South could not defend every acre of Southern territory, nor could it replace the soldiers it was losing now--but the North could replace its losses. Therefore he would wage total war, and win by causing more destruction than the other side could inflict.

Against Lee's 60,000 or so Confederates, Grant began the campaign with 157,700 Union troops. These started out divided into three forces. Franz Sigel took 6,000 into the Shenandoah Valley, while Benjamin Butler got a second chance to attack Richmond from the east, marching up the Peninsula from Fort Monroe with 33,000. Grant and Meade led the remaining 118,700 in a simple frontal assault, marching due south to see how close they could get to Richmond before Lee interfered with their progress.

What really slowed the Union advance wasn't the Confederates so much as the Wilderness, the same dense forest that had masked troop movements in the battle of Chancellorsville, a year earlier. Both Grant's and Lee's forces entered here on May 5, and the thick growth made it impossible to use cavalry or artillery, so the battle of the Wilderness was mainly a duel of groping infantry, because they could barely see each other. Organization broke down completely under these conditions, and in many areas brush fires incinerated soldiers who could not get out of the way. After two days, Grant had lost 18,400 men and Lee had lost 11,400; Grant gave the orders for the Union Army to pull out. It looked like Lee had won another victory, and that this Northern campaign would end like so many others over the past three years--with a retreat to Washington.

It was at this point that an observer would see that things had changed. At the first crossroads reached by the boys in blue, General Grant himself was standing by the road. He was holding a cigar (Grant smoked two dozen on just the second day of the battle) and pointing south to Richmond, not north to Washington. According to the story told afterwards, the men cheered when they saw this, and made a right turn instead of going forward, resuming their advance by marching around Lee's right flank. At last, the Army of the Potomac had a general who would not let Robert E. Lee boss him around.

The next stop on the road after the Wilderness was Spotsylvania, ten miles to the southeast. The Confederate Army still moved faster than the Union one, so Lee got there first, though his troops had to march overnight to do it. The battle of Spotsylvania Courthouse was a drawn-out affair, lasting from May 8 to 21. Lee arranged his men in an arrowhead-shaped formation that would allow his artillery to fire to the sides as well as forward, but the Union generals concentrated their fire on the point of the Confederate "arrowhead" until they broke through on May 12. This would have been a disaster for the Army of Northern Virginia if the Union troops followed up on this success to split the army into two or more pieces, and Lee decided to personally lead the force that would restore the Confederate line. His soldiers refused to allow their general to put himself in such a dangerous spot; they insisted that he go back to the rear, and after several hours of bayonet fighting (unusual, since most battles involving bayonets are short), they managed to push the Yankees back and form a new defensive line by themselves. By the time Grant realized he wasn't going to dislodge the Confederates from here, there had been 18,000 Union casualties and 12,000 Confederate ones. Among the deaths were generals on both sides; the North lost John Sedgwick, and the South lost Jeb Stuart. Grant withdrew by performing the same maneuver that had come after the last battle, moving east and then south to go around the Confederates and continue down the road to Richmond.

Meanwhile, Confederate victories on the other fronts in the Eastern Theater gave Lee some much-needed reinforcements. For the Shenandoah Valley, Major General John Breckinridge, the former vice president and Democratic presidential candidate, assembled a force of 4,500, which included 247 teenage cadets from the Virginia Military Institute. On May 15 he attacked Sigel at New Market, and soon suffered enough losses that he had to use the cadets; they led a charge that broke Sigel's line and won the battle. Sigel lost 831 men; among Breckinridge's 577 losses were ten VMI cadets dead and forty-seven wounded. With the Valley apparently secure, most of the Confederates were now transferred to Lee. Then in early June, Grant replaced Sigel with a tougher general, David Hunter, who entered the Valley, overwhelmed the token Confederate force remaining, and cut east across the mountains to Lynchburg.

Since Butler bungled his first Virginia campaign, he had served as military governor of New Orleans, but did a poor job even with a garrison assignment. Now he made things difficult for Grant by messing up again. Opposing him was a Confederate "army" half the size of his own, led by P. G. T. Beauregard. Besides soldiers, Beauregard's force included teenagers, old men, members of the local militia, and shopkeepers, obtained the scraping the bottom of the manpower barrel in the Richmond-Petersburg area. Butler shouldn't have had any trouble dealing with this motley crew, but when Confederate resistance to his advance became tougher than expected, he withdrew to Bermuda Hundred, a town at the junction of the James and Appomattox Rivers. Beauregard promptly spread his men across the side of the town not bordered by the rivers, trapping Butler inside. Disgusted at Butler's timid behavior, Grant noted that his force was "as completely shut off from further operations . . . as if it had been in a bottle strongly corked." There they stayed until the siege of Petersburg began; when they finally broke out, Grant no longer needed them.

In the middle of the battle of Spotsylvania Courthouse, Grant said, "I propose to fight it out on this line if it takes all summer." He ended up doing even more than that. Again Lee raced to put the Army of Northern Virginia between the Army of the Potomac and Richmond. When they met again, on the banks of the North Anna River, there were four days of minor engagements (May 23-26) before Grant withdrew and went around Lee's army a third time. The prisoners captured at North Anna convinced Grant that Lee's army was in really bad shape, and that it would fall apart soon. This is probably why at the next meeting between the armies, the battle of Cold Harbor, Grant tried a head-on attack (May 31-June 12). Instead, it was a Northern massacre; Union troops made fourteen assaults, none of them successful, and more than 7,000 fell dead or wounded in just the first half hour. Part of the reason for the horrible losses was that the Union army at this point was largely made up of inexperienced recruits and heavy artillery troops, pulled from the defenses of Washington, D.C., to replace the casualties from previous battles, while most of Lee's men were veterans, entrenched in impressive fortifications. By the time Grant withdrew from Cold Harbor, he had lost 13,000, against 2,500 losses on the Confederate side. Critics of Grant were quick to call him a "fumbling butcher," and pointed out that in five weeks his campaign had consumed 55,000 Northern troops, almost as many men as Lee had in his whole army, but he was no closer to Richmond than McClellan had been, two years earlier.

What was different was that Grant had gained the initiative and kept it. He had just lost four battles, but paradoxically, after every one he ended up closer to Richmond than he had been before. After Cold Harbor, he decided that Richmond would be too tough to take at this stage, so instead he crossed the James River, went past Richmond, and turned his guns on Petersburg, the next city to the south. Capturing Petersburg would leave Richmond surrounded on every side except the west, and with Hunter at Lynchburg, it looked like the west wouldn't be open much longer, either. However, Petersburg was also well-defended; Grant found this out when Lee and Beauregard threw in everything they had to defend the city from Grant's first attack (June 15-18). Grant thus chose to put Petersburg under a Vicksburg-type siege, and to do this, he would have to leave the road between Richmond and Washington wide open; the fact that he left it open meant he no longer had to worry much about what the Confederates might do.

The Confederates did attempt one more northern invasion while the way was open. To relieve the growing stranglehold on Petersburg and Richmond, Lee sent General Jubal Early against Hunter in Lynchburg. Early won the first encounter, and Hunter, short on supplies, fled back to West Virginia. Now the Shenandoah Valley was open, and Early went up it, bypassed Harper's Ferry, and entered Maryland. At the battle of Monocacy, near Frederick, MD (July 9), Early defeated the force Grant had detached from Virginia to defend Washington, but the one-day delay caused by the battle allowed other reinforcements to arrive. Two days later he attacked Fort Stevens, on the outskirts of Washington, decided that the Northern capital's defenses were too strong for his small, extended force, and withdrew, burning Chambersburg, PA before returning to Virginia. The battle of Fort Stevens, besides being the last Confederate attempt against Washington, is noteworthy because Lincoln rode to the front line to watch the action, making him the only president to come under enemy fire while in office.

Next, Grant ordered Hunter back into the Shenandoah Valley. His purpose, as Grant put it, was "to eat out Virginia clear and clean as far as they go, so that crows flying over the balance of the season will have to carry their provender with them." Hunter hesitated and Grant replaced him with the cavalry commander of the Army of the Potomac, Philip Sheridan. Sheridan was more willing to go after Early, and after four minor engagements in late August-early September, he won two larger battles at Opequon Creek (September 19) and Fisher's Hill (September 22); Early lost 5,000 of his 12,000 men and began to retreat. Then Sheridan's force pulled back to the northern part of the Valley, and applied the same scorched-earth policy on the land as Sherman was using in Georgia. Early received enough reinforcements from Lee to bring his army back up to 12,000, returned and launched a surprise attack at Cedar Creek that routed two thirds of Sheridan's army (October 19). Sheridan was returning from a military conference in Washington when this happened, and covered the last ten miles from Winchester to Cedar Creek in a fast ride that captured the imagination of Northerners. Once there he rallied his broken units and led a counterattack on the Confederates, who were so tired and hungry that they had paused to loot the Union camp; Early lost 2,910 men, 25 cannon, and most of his supply wagons. The Confederates were forced to abandon the Valley; the "Breadbasket of the Confederacy" had changed hands for the last time.

One more battle in the Eastern Theater for 1864 deserves mentioning, the "battle of the crater." Both Lee and Grant knew that if the Confederates came out of their trenches, the Union troops would overwhelm them, so Lee kept them dug in, and Grant extended his lines around Petersburg and Richmond as reinforcements became available, until they were more than twenty miles long. Grant reasoned that if he continued to do this, he would eventually cut the last two railroads leading into Richmond, and the Confederate line would be stretched to the point that it could no longer defend every sector, allowing a breakthrough at a time and place of Grant's choosing. But even he was willing to try alternative methods, if they promised a quicker, less bloody way to win. Accordingly, he listened when Lt. Colonel Henry Pleasants, who had been a mining engineer in Pennsylvania before the war, came to him with a proposal. Pleasants wanted to dig a tunnel under a fort on the Confederate line near Petersburg, fill it with gunpowder, and set off the charge, causing a major breach that would destroy the fort and leave Petersburg defenseless. It was a modernized version of the medieval practice of mining, where besieging soldiers would dig tunnels under a castle in the hope of bringing down the walls. Grant and Meade agreed that it would keep the soldiers occupied, whether or not the plan worked, and gave their approval to it in late June.

On July 30 the tunnel was finished and the gunpowder exploded, creating a crater 170 feet long, 60 feet wide and 30 feet deep; 278 Confederates were killed in the blast. Unfortunately, what should have been an ingenious diversion then turned into a massacre; Ambrose Burnside was commander over the army unit that had done the digging, and Grant and Meade ordered him not to have black soldiers in the first assault, because a lot of them were likely to get killed needlessly if it failed, and that would look bad when the press reported it. Burnside responded by sending an inexperienced white division instead, and they went into the crater, thinking it would make a good, oversized foxhole. All the Confederates had to do was line up around the rim of the crater and shoot downward; it was literally like shooting fish in a barrel. Then Burnside sent in the black division that was supposed to go originally, and it was trapped as well; it took fearsome hand-to-hand fighting for any of the Union troops to escape at all. By the time it was over, Union casualties were estimated at 4,000-5,300 men, compared to 1,200 estimated Confederate losses. Afterwards, both sides had no choice but to go back to the siege tactics practiced before the battle. When Lincoln heard the news, he remembered how Burnside had performed at Antietam and Fredericksburg, and said, "Only Burnside could have managed such a coup, wringing one last spectacular defeat from the jaws of victory."

Campaigns of 1865

From the North's point of view, Sherman and his army disappeared when they left Atlanta, and reappeared in Savannah. From here the plan was to have Sherman march through the Carolinas, knocking those states out the war as he had done with Georgia, and join Grant in Virginia to finish off Lee. Sherman's troops especially wanted to punish South Carolina, for starting the war in the first place. However, bad weather forced them to take January off; the army didn't leave Savannah until February 1.(30) In South Carolina they met little resistance, and several towns in the Palmetto State went up in flames, including Columbia, the state capital, which was taken on February 17 (to this day it is not clear how many of the fires in Columbia were started by retreating Confederates, and how many by vengeful Union soldiers). Meanwhile on the coast, the US Navy captured Charleston and Fort Fisher (near Wilmington, NC), leaving Galveston, TX as the only port left for Confederate blockade runners.

Sherman entered North Carolina on March 8, took Fayetteville, and then sent his army ahead in two columns to seize Goldsboro, an important railroad junction. Joseph E. Johnston arrived at Bentonville with 18,000 men, the last remnant of the once-proud "Army of Tennessee," and threw them at Sherman's left wing, in the hope that would stop the Yankees. The battle of Bentonville raged for three days (March 19-21), until the two wings of Sherman's army reunited and drove off Johnston. Instead of pursuing the retreating Confederates, Sherman went on to Goldsboro, and his army camped there for the last two weeks of the war.

The last campaign of the war in the Western Theater was a raid into the Rebel-held parts of Alabama and Georgia, led by James Wilson. A veteran of Sheridan's 1864 "Valley Campaign" and the recent battles for Franklin and Nashville in Tennessee, Wilson had done such a fine job with the cavalry entrusted to him that he was promoted to the brevet rank of brigadier general, though he was only twenty-seven years old. The purpose of the raid was to destroy the Confederate arsenal at Selma, AL, and Wilson began it by leaving Gravelly Springs, AL with 13,500 men on March 22. Nathan Bedford Forrest tried to stop Wilson when he realized that Selma was the objective, but Wilson knocked him out of the way at the battle of Montevallo (March 31), won another battle at Selma before taking the city of April 2, and spent several days destroying the military facilities there before moving on to take Montgomery (April 12). Unlike Sherman, however, Wilson made sure civilian targets like roads and houses were not attacked. In mid-April he heard the news of Lee's surrender and Lincoln's death, but instead of stopping, headed east for Georgia. He took Columbus, GA on Easter Sunday (April 16), and Macon on April 20, before finally settling down and declaring the raid over. His men had captured five fortified cities, 288 cannon, and 6,820 prisoners, at a cost of 725 Union casualties, while inflicting 1,200 casualties on the much smaller force of Forrest.

In Virginia, it was clear that the CSA was on its last legs as 1865 began. Hope that the South could win, or at least fight the North to a draw, faded after Lincoln was reelected. The Union Navy blockade and General Sherman's campaigns had isolated Confederate-held Virginia from the rest of the territory still under Confederate rule (mostly in Alabama, Florida and Texas). Around Petersburg and Richmond, the Confederate Army was suffering badly from the siege, illness, malnutrition, and lack of clothing, to the point that some called the troops "Lee's Miserables." Desertions were also mounting; 1,094 Southerners simply disappeared from the Petersburg trenches, in a ten-day period in February. And when it came to replacing those losses, the battles of 1864 showed that the Confederacy was running short on able-bodied white men. Some Southerners saw arming the slaves as the solution to this problem (see footnote #19). In the past there had been civilizations with armies of slaves (e.g., the Arabs had the Mamelukes, the Ottoman Turks had the Janissaries), but in America the slavery issue was so emotional that nobody expected a slave to remain obedient, once he had a weapon. Arming the slaves would only work if they and their families were freed as well. Jefferson Davis refused to consider the idea when it was first proposed, but as 1864 dragged on, the military situation grew critical, and Lee insisted on it, arguing that it was more important to protect the South than to defend the institution of slavery. Finally Davis gave in, stating that slaves could enlist if they had their owners' permission. Training of the first all-slave units in Richmond began in March 1865, so the war ended before they saw any meaningful action. Davis also sent a message to Great Britain and France, announcing that he would abolish slavery in return for diplomatic recognition. Again, it was too late to make a difference; the war ended before the European powers could respond. The South went down fighting, but during the last weeks it wasn't clear what it was fighting for.

On March 2, Sheridan captured Waynesboro, VA, bringing his Valley Campaign to a successful close. From there he rode east to join Grant. Sensing that the end was near, Lincoln went to the front, meeting with Grant, Sherman and Admiral Porter on the River Queen, a few miles downstream from Richmond (March 28). There Grant persuaded the others that he should not have to wait until Sherman arrived before making the final assault on Richmond; the Army of the Potomac had already earned the right to do it by itself. Grant began that assault right after the conference, by sending Sheridan into the area seventeen miles southwest of Petersburg, the target being Lee's last supply line, the South Side Railroad. Lee sent General George Pickett to defend Five Forks, a crucial road intersection, and when Sheridan defeated Pickett (the battle of Five Forks, April 1), the Confederate line collapsed. All along a forty-mile front, Union troops surged forward, overrunning those Confederates who did not get out of the way. Lee abandoned Petersburg, and since he could not defend Richmond without Petersburg, he gave the orders to evacuate Richmond, too. Anything that the army and the government could not take with them was to be burned, and the mob quickly got out of control, burning down much of the Confederate capital before Union troops entered both cities on April 3. Behind them came Lincoln, guarded by a dozen armed sailors and a unit of joyous black soldiers. Without saying much, he stayed just long enough to look around, visit Jefferson Davis' office and sit in his opponent's chair. To Grant he sent a telegram that told him to finish the war with these words: "Gen. Sheridan says 'If the thing is pressed I think that Lee will surrender.' Let the thing be pressed."

Richmond in ruins.

The Confederate government escaped to Danville, VA, where it spent the last week of the war. Lee tried to follow, the idea being that he would join his force with Johnston's as it came up from North Carolina. Instead, Sheridan's cavalry blocked the way to the south, forcing him to go west. At Amelia Courthouse, the first town west of Richmond, Lee hoped to find a train loaded with supplies for his footsore, hungry soldiers, but the train missed them, continuing on to Richmond (where it was captured). On April 6 a third of the Confederate Army was trapped at Sayler's Creek and forced to surrender. After two more skirmishes at Farmville and High Bridge, the rest of them reached Appomattox Courthouse on April 8. Here they found that Union cavalry, led by General George Armstrong Custer, had arrived first and burned the three supply trains waiting for the Confederates. Lee considered moving on to Lynchburg, but that night he saw campfires in every direction, meaning that Grant's army had surrounded him. A final battle the next morning convinced Lee that he would not be able to break out, and he sent a letter to Grant, asking for terms. Thus, at 2 PM on April 9, 1865, Grant and Lee met at a farmhouse to arrange the surrender of the last soldiers in the Army of Northern Virginia. Remembering that Lincoln wanted to end the war with as little bloodshed as possible, Grant offered extremely lenient terms, and Lee accepted them with both gratitude and despair.(31) All Confederate soldiers would be allowed to go home without punishment, once they agreed to obey the laws of the land and not take up arms against the Union again. Officers were allowed to keep their sidearms, and those with horses or other draft animals were allowed to keep them for the spring plowing they would have to do very soon.(32)

The End of the CSA

Officially the war ended with Lee's surrender at Appomattox, but it would take the rest of April and May to end the fighting and restore the federal government's authority, all over the South. Among those killed in the pacification phase was Lincoln himself. On the night of April 11 he stepped out on the White House balcony and read the Appomattox terms to the crowd below, and announced that his policy for rebuilding the South would be one of forgiveness, not revenge. Each Southern state could rejoin the Union once ten percent of its white citizens took an oath of allegiance and formed a new state government. The issue of "Negro suffrage" would be left to each state, but Lincoln hoped that the states would allow blacks, especially veterans of the Union Army, to vote. One of those in the crowd who heard this was John Wilkes Booth, an unemployed actor and Southern sympathizer, and he said to his companion, "This means n*gg*r citizenship. Now, by God, I'll put him through!" Three nights later, Lincoln and his wife went to Ford's Theater to see the play "Our American Cousin," and when the bodyguard, a confused Washington policeman, left his post for a drink of whiskey, Booth sneaked into the balcony and shot Lincoln in the head. Lincoln died the next morning; though his work of preserving the Union was finished, it would fall upon his vice president, Andrew Johnson, to carry out the difficult task of Reconstruction.

On April 17, Generals Johnston and Sherman met in Durham, NC, to discuss the terms of surrender for all Confederate forces in the Carolinas, Georgia and Florida. Thinking that Lincoln would have wanted it that way, Sherman offered even more generous terms than Grant had offered Lee. They were so generous, in fact, that Stanton rejected the agreement and ordered Sherman to renegotiate.(33) Johnston ended up surrendering twice; the second time, on April 26, it was under the same conditions that Lee had agreed to. Jefferson Davis met with the Confederate Cabinet for the last time in Washington, GA on May 5, where they agreed to dissolve the CSA government. On May 10, Davis was captured at Irwinville, GA, where he had tried to disguise himself by wearing his wife's raglan and shawl; he was imprisoned for two years, making him one of the few Confederate leaders to do any time in jail.

As May began there were two Confederate armies left west of the Mississippi, one led by General Richard Taylor in Louisiana, the other led by General Edmund Kirby Smith in Texas. Taylor collected those soldiers from Nathan Bedford Forrest's army that survived Wilson's raid, and surrendered to General Edward R. S. Canby (on May 4, in Citronelle, AL). Smith also surrendered to Canby, at New Orleans on May 26.(34) A few diehard Rebels, like General Sterling Price of Missouri, chose to flee to Latin America, rather than surrender.

Reconstruction

The end of the Civil War gave Americans a new set of challenges. First, the nation had to switch from a wartime to a peacetime economy. Second, most of the armed forces would be demobilized, now that they were no longer needed. There was a war scare with France, because the French had invaded Mexico, prompting President Johnson and General Grant to send 50,000 troops to the Mexican border as soon as the Civil War ended, but that threat faded when the French withdrew in 1866. By November 1865, the War Department had mustered out 800,000 men, about half the army; two years later, the US army was down to 57,000 men, still larger than it had been before the war, but not by too much. Third, the South would have to be rebuilt to run on free labor. And fourth, a place would have to be found in American society for the former slaves, now called "freedmen."

The Northern states had continued to industrialize, and development of the West continued, while the war was going on. 900,000 immigrants came to the Northern states during the war years, more than offsetting the number of Yankees killed in battle. However, the immigrants competed for jobs with the ex-soldiers who were trying to return to civilian life, causing an economic recession in 1866 and 1867.

Still, the problems facing "Billy Yank" at home were mild, compared to what "Johnny Reb" faced; ex-Confederates might not even have a home to return to. Because only a few battles (Gettysburg was the main one) were fought in Union states, most of the war's devastation was in the South. The economy, railroads, and the entire infrastructure of the former Confederacy had been destroyed. Most ex-Confederate soldiers had to travel on foot, usually in small groups to protect themselves from deserters who had become brigands to make ends meet. Broken levees left much of the lower Mississippi valley flooded, farms and large houses had been burned, and livestock had been killed or turned loose. There was a particularly bad incident in Mobile, AL, where a federal ammunition dump exploded on May 25, 1865, killing three hundred people and destroying much of the city. On top of all that, inflation had made the Southerner's money worthless, even when left in a bank account, and if he sold his land, he would get less than ten percent of its prewar value.

In the middle were those Southern states which had stayed with the Union: Delaware, Maryland, West Virginia, Kentucky and Missouri. They did not attract as many immigrants as the North, were not damaged badly by the war, and were spared from the pains of Reconstruction. Even so, they faced problems of their own. The most famous problem was the Hatfield-McCoy feud, fought between two families on opposite sides of the Kentucky-West Virginia frontier. This struggle lasted for twenty-eight years (1863-91), prolonged because it took place in a nearly inaccessible part of the Appalachian mts., and was exacerbated by the poverty of the region. Later on came a more serious feud, the "Rowan County War" (1884-87) in Morehead, KY. This time 20 were killed and 16 were injured; it also became a political struggle, with the Republicans of Morehead supporting one family (the Martins) and the Democrats supporting the other family (the Tollivers). Three times the state militia was called in during the feud, and at one point a state report recommended that Rowan County be dissolved because of the violence.

In the war-ravaged South, the ex-slaves, being poor to begin with, suffered the most. Because there wasn't any other place for them to find employment, 75 percent of the freedmen stayed to work on the plantations of their former masters. Most of them now became sharecroppers, and when they went into debt (which happened all too often if their crops did not bring in enough profit to pay for seed, tools and rent), they found themselves bound to the land by financial obligation, instead of by chains. At this stage, the only blacks with much hope for getting ahead in life were those who had gone to the cities and learned new skills. Frederick Douglass, an ex-slave himself, described the misery of the freedmen with these words:

"The world has never seen any people turned loose to such destitution as were the four million slaves of the South . . . They were free! Free to hunger, free to the pitiless wrath of enraged masters. . . . Free, without roofs to cover them, or bread to eat, or land to cultivate."

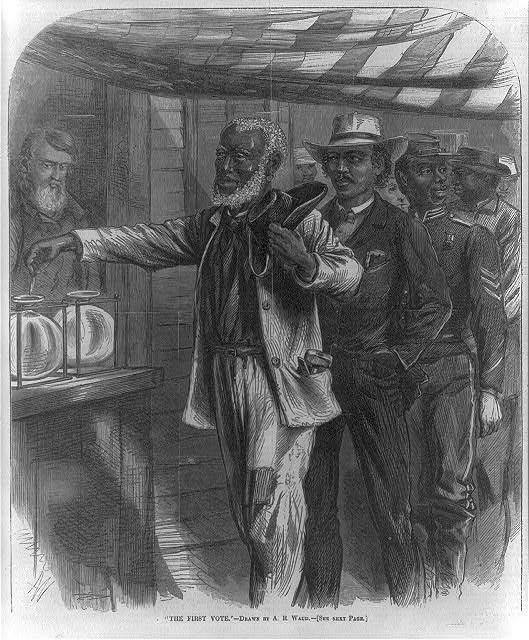

Congress helped the freedmen by passing several key pieces of legislation. The first, the Thirteenth Amendment, had already been passed in January 1865; it abolished slavery once and for all. In March the Freedmen's Bureau was established as a branch of the US Army. This agency set up schools for blacks, provided schools and medical supplies, held special black courts, and regulated the wages and working conditions of blacks. During the next four years Congress also passed the Civil Rights Act, the first civil right law on the books of the federal government; the Fourteenth Amendment, which guaranteed the full rights of citizenship to anyone born in the United States, except Indians; and the Fifteenth Amendment, which gave all men the right to vote, regardless of race. President Johnson vetoed both the Civil Rights Act and a bill to extend funding for the Freedmen's Bureau beyond 1866; by overriding those vetoes, Congress managed to keep the Freedmen's Bureau going until 1869.(35)

The Freedmen get to vote.

For a year and a half after Lincoln's death, Andrew Johnson tried to implement Lincoln's moderate "ten percent" plan to bring the South back into the Union. His troubles started with his inauguration in 1865, when he had yellow fever and tried to cure it with three drinks of bourbon. After listening to a speech from the previous vice-president, Hannibal Hamlin, he gave a speech so loud and embarrassing that Hamlin tried to pull him back in his chair by his coattails, while Lincoln showed an expression of "unutterable sorrow," and Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner covered his face with his hands. Then Johnson took the oath of office, kissed the Bible, and tried to swear in the new senators, but became so confused that he had to let a Senate clerk finish the job. Later he told a Washington street crowd he would hang Jefferson Davis and the whole "diabolical" crew in Richmond if he got the chance, but after becoming president he hanged almost nobody; his policy was leniency for former rebels and benign neglect for former slaves. Coming from a poor family, Johnson hated Southern aristocrats, blamed the war on a few rich Southerners, and felt that once they were gone and the slaves were free, nothing more needed to be done to change the society of the South. He offered amnesty to anyone who would take the oath of allegiance, except for those with a postwar net worth of more than $20,000; the latter had to apply to him personally for pardon, but he usually granted it anyway. Though he had been against slavery, Johnson was still a white supremacist; that's why he wasn't too eager to give blacks assistance. "This is a country for white men," he explained, "and, by God, so long as I am president, it shall be a government for white men." Accordingly, he canceled General Sherman's Special Field Order No. 15 (see footnote #30) and ordered the return of abandoned plantations to their former owners. Southern whites were pleasantly surprised to find that while the president had been on the other side during the war, he was still one of them.

Congress came back from a long recess in December 1865. Its members didn't like what had happened while they were away. By this time enough Southerners had sworn allegiance for each Southern state to form a new government and return to the Union, so Johnson regarded the reconstruction of the South as complete. However, the reinstated South held new elections before its blacks could vote, thereby making sure whites would remain in charge. The Southern states also passed "Black Codes," laws designed to keep the freedmen subjugated; in South Carolina, for instance, blacks were required to go to bed early, rise at dawn, speak respectfully to their employers, and do no skilled work without a license. Worst of all, from the Northern point of view, Southern voters turned to the leadership they were familiar with, and elected a bunch of Confederate officials, including Former Vice-president Stephens, as their congressmen. Both moderate and radical Northerners were offended; what was the point of winning the war, Pennsylvania Representative Thaddeus Stevens asked, if the enemies of the Union could use the ballot to march back to Washington, take over the Senate, and maybe even win the White House? The Republican response was to reject all Southern Congressmen; they simply refused to swear them in. Even Horace Maynard, a Tennessee representative who had always been loyal, was not admitted.

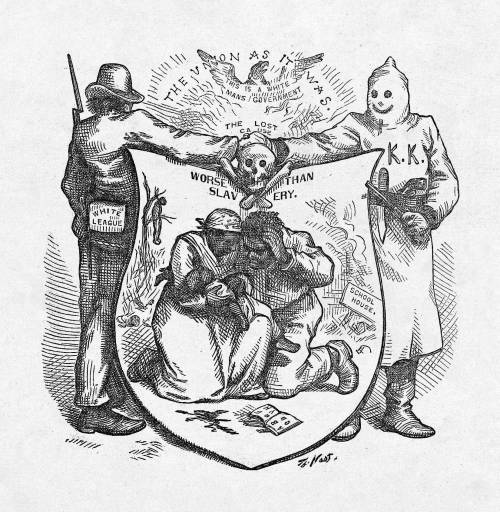

Stories of racial unrest further alarmed the North. Because local government was weak or nonexistent in many parts of the South, and there were fears of ex-slaves seeking revenge on their former owners, vigilante groups were set up in many areas to stop roaming thugs and lawlessness, with names like Men of Justice, the Pale Faces, the Constitutional Union Guards, the White Brotherhood, the Order of the White Rose, and the Knights of the White Camelia. The most famous of them, the Ku Klux Klan (from the Greek kuklos, meaning "circle") was founded in Pulaski, TN, by six Confederate officers in December 1865; eventually it absorbed many of the other groups. Dedicated to defending white supremacy and the Democratic party, the Klan scared its victims with strange disguises, silent parades, midnight rides, and mysterious commands; their favorite trick was to wear white sheets and masks, pretending to be the ghosts of Confederate soldiers.

While the Ku Klux Klan preferred psychological warfare, others acted with real violence. On May 1, 1866 came the worst race riot in the history of Memphis. It began with a clash between local white policemen and black federal troops, and soon the city's white residents got involved. Over the next two days rioters attacked buildings belonging to the black community of Memphis; by the time martial law was declared, two whites and at forty-six blacks were killed, between seventy and eighty others were wounded, at least five black women raped, more than one hundred people (mostly black) robbed, and four churches, twelve schools, and ninety-one houses had been burned. Another riot occurred in New Orleans on July 30, when radical Republicans held a convention to write a new constitution for Louisiana, one that did not include a Black Code, and an armed crowd of Democratic anti-Abolitionists and Confederate veterans tried to break up the meeting. This time the toll was forty-nine dead, 176 injured. Previously many had thought racial equality would come once blacks could vote, but now this clearly wasn't happening.

We already mentioned Johnson's unsuccessful attempt to limit action in the South by using the power of the veto. For the rest of 1866, Johnson behaved so ineptly that Charles Sumner remarked, "the President himself is his own worst counselor, as he is his own worst defender." He called the radicals traitors for keeping the Union apart, and that cost him a lot of respect from moderates. When the 1866 congressional elections approached, he campaigned for the National Unity Party again, figuring that this coalition would support him and his policies. Instead those members who had been Republicans before 1864 returned to the Republican Party, leaving him with a small faction of the Democratic Party, the "War Democrats." In many congressional races there wasn't a National Unity candidate to run, leaving the voters with a choice between a radical Republican and a Copperhead Democrat. Most went with the former, and the Republicans won by a landslide; the next Congress had 57 Republican senators (out of 68) and 173 Representatives (out of 226)--more than three quarters of all seats.

With that crushing majority, the Republicans could do almost anything they want, and now the radicals, led by Charles Sumner in the Senate and Thaddeus Stevens in the House, introduced their plan to rebuild the South in their image. In March 1867 they passed the Reconstruction Act, which dissolved the governments of ten Southern states, and placed them under martial law in five military districts, each administered by a major general:

- Virginia, under General John Schofield.

- North & South Carolina, under General Daniel Sickles.

- Georgia, Florida and Alabama, under General John Pope.

- Mississippi and Arkansas, under General Edward Ord.

- Louisiana and Texas, under Generals Philip Sheridan and Winfield Scott Hancock.

The new state governments set up under the Reconstruction Act were Republican, of course, and made up of people from three groups: blacks, Northerners who entered Southern politics, and Southern whites who agreed with them. Blacks made the most impressive gains, moving into many offices that had previously been for whites only, and gaining valuable experience. In fact, the surprise is that more of them weren't elected, because the majority of eligible voters in the South at this stage were black. At the state level, only South Carolina produced a legislature with a black majority. At the national level, fourteen black representatives and two black senators (both of them from Mississippi) went to Congress; one of the senators, Hiram Rhodes Revels, filled a seat that had last been occupied by Jefferson Davis. The other, Blanche Kelso Bruce, received some votes at the 1880 Republican convention, becoming in effect the first African-American candidate for president. Because they had been slaves just a few years earlier, the new black politicians were a powerful symbol of change for supporters and opponents of Reconstruction. Another was the public school system; Republicans believed that education would ultimately solve the problems of poverty and ignorance, so under them many parts of the South, especially rural areas, got schools for the first time.

Many Southerners thought worse about the North during Reconstruction than they had during the Civil War. Most of the Northerners involved in Reconstruction were ex-Union soldiers and officials from the Freedmen's Bureau; the rest were businessmen looking for a chance to invest in Southern cotton, plus some schoolteachers and missionaries. Whatever their background, they were given the nickname "carpetbaggers" by Southerners, referring to the cheap luggage made from carpets that they used to bring their belongings with them. Likewise the Southern whites who joined the Reconstruction-era governments were derided as "scalawags," meaning rascals, whether they did it because of principle or because they saw an opportunity to get ahead. To the typical Southerner, carpetbaggers were oppressors and scalawags were traitors.

Against both them and uppity blacks, the Ku Klux Klan added whippings, mutilations and lynchings to the previously mentioned scare tactics, in effect becoming the terrorist wing of the Democratic Party. In 1867 an attempt was made to organize the Klan on a national level, with ex-General Nathan Bedford Forrest as its Grand Wizard or leader. However, they couldn't agree on rules for the organization; local chapters became uncontrollable, and the army was quick to crack down, when Southern whites were afraid to do so. Forrest ordered the Klan to disband in 1869, stating that it was "being perverted from its original honorable and patriotic purposes, becoming injurious instead of subservient to the public peace." Other Southerners saw the Klan being used as an excuse by Washington to keep soldiers in the South. Congress passed laws in 1870 and 1871, ordering the enforcement of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, and giving the president the power to suspend the writ of habeas corpus when prosecuting Klan violence. In Louisiana a dispute over who won the 1872 state elections led to the bloodiest incident of the Reconstruction era, the Colfax Massacre (April 13, 1873), when members of the Ku Klux Klan and the White League, another racist group, clashed with the mostly black state militia at a courthouse; it is believed 105 were killed, but nobody was sure because some of the bodies had been buried or hidden. Eventually the federal government broke up local Klan chapters by arresting their members, but it was the end of Reconstruction, and the return of blacks to second-class status, that really restored order; many Southerners felt the goals of the Klan had been achieved, even if the Klan itself no longer existed.

The Reconstruction Act effectively wiped out everything Lincoln and Johnson had done over the past two years. Predictably, Johnson vetoed the act, and just as predictably, Congress used a two-thirds majority to pass over his veto again. Then the radicals added to the insult by passing two more laws, making it illegal for the president to dismiss members of his own Cabinet, or to transfer the commander of the US Army (currently General Grant) without the approval of Congress. Johnson wasn't the type to shy away from a challenge, so he fired a favorite of the radicals, War Secretary Stanton. Stanton simply refused to leave his office, and Congress responded by impeaching the president, the first time that had been done in American history.

The laws which the radicals had shackled Johnson with were eventually declared unconstitutional, but that didn't happen until 1926, far too late to prevent impeachment. In fact, Johnson hadn't even broken those laws, because Stanton had not been appointed to the Cabinet by Johnson, but by Lincoln. The real reason for the impeachment was politics; Sumner admitted as much, calling it the "last great battle of slavery." Thaddeus Stevens, now seventy-six years old and so ill that he had to be carried into the meetings, said to the other committee members at one point, "We had better put it on the ground of insanity or whisky." In the end the radicals charged Johnson with eleven "high crimes and misdemeanors" that were really quite trivial. It took a two-thirds majority, or a vote of 36-18 in the Senate, to convict Johnson and remove him from office. Instead the final tally was 35-19; Johnson's presidency had been saved by one vote.(38)

Looking back, we can see the impeachment proceedings were rather pointless, because the trial took place in the spring of 1868, less than a year before the end of Johnson's term. All the trial did was make sure Johnson would not run for reelection, because it kept him too busy until both the Republicans and Democrats had nominated somebody else. Radical power on Capitol Hill was broken with the acquittal; Stevens died less than three months after the trial ended, and the 1868 elections gave the United States both a president and a Congress that were more willing to get along.

The Free State of Van Zandt

One part of the South that wanted nothing to do with slavery and Reconstruction was Van Zandt County, in northeastern Texas. Almost no one in this county owned slaves, and they didn't like the idea of fighting for someone else's right to own slaves. So when Texas seceded in 1861, some folks in Van Zandt County proposed seceding from Texas, so they could remain with the Union. However, the threat of military intervention by the state of Texas was enough to keep the citizens of Van Zandt from acting, for the duration of the Civil War (compare this with footnote #8).

After the war, the citizens of Van Zandt decided that another thing they didn't like was letting Union troops and carpetbaggers run around in the county. In 1867 Texas was readmitted into the Union, and a convention was held in Van Zandt to propose seceding from Texas, the Confederacy, and the United States of America! The county commissioners approved of this move, and drafted a declaration of independence, which looked a lot like the more famous 1776 Declaration of Independence.

Naturally General Sheridan saw this move as an act of rebellion, and he sent a cavalry unit to deal with it. However, the heavily forrested terrain of Van Zandt County canceled the advantage cavalry normally has, and the rebels knew their home ground well enough to surprise their opponents. The first (and only) battle of the Free State War was won by the rebels, who ambushed and drove off the cavalry. Then, to celebrate the ultimate David-vs.-Goliath victory, the rebels gathered in Canton, the main town of Van Zandt County. At the party they drank too much, and while they were totally blotto, Sheridan's troops returned, arrested the whole bunch, and built a stockade near Canton to hold them.

You'd think that would be the end of the story, but it has an epilogue. One of the prisoners, a former Confederate soldier named William Allen, had a knife in his boot that was not discovered by his captors, and over the course of several days he used the knife like a file, wearing down the anklets restraining him until he could break them off. Around the same time the rainy season started, and the guards posted on the site were reduced to one, who did his best to keep an eye on the prisoners by simply walking around the compound. This allowed Allen to free the other prisoners while the guard wasn't looking, and when they broke out of the stockade, most of them fled in two different directions, one group going north to the Indian Territory (Oklahoma) and the other going west to the neighborhood of Waco, TX.

Arrest warrants were put out for all the prisoners that escaped, but Federal troops did not look very hard for them, and none were caught. Even Allen was able to return after most people forgot about the affair, and he spent the rest of his life as a doctor in Canton. As for the Feds, they departed as soon as they brought Van Zandt County back into Texas, considering their work complete. Nobody bothered to void the county's declaration of independence, so technically the county is still independent. Today the county calls itself "The Free State of Van Zandt," though today it isn't clear if it got that name from the 1867 secession, the 1861 secession attempt, the county's lack of slaves, or some incident that happened even earlier.

The Alaska Purchase, and the Only American Emperor

Before we move on to the next section, we should mention the biggest foreign policy success of the Johnson administration. One night in 1867, Secretary of State William Seward received a visit from the Russian minister in Washington, Baron Edouard de Stoeckel, with a surprise offer from the Tsar: he would sell the colony called Russian America for $7,200,000. Seward knew those kind of deals don't come every day, and offered to buy immediately. Stoeckel didn't see how, protesting, "But your Department is closed," and Seward, showing that Russians weren't the only ones who could coerce their underlings when necessary, replied, "Never mind that. Before midnight you will find me at the Department, which will be open and ready for business." Thus, before the next morning Seward bought Alaska for a price that worked out to only two cents an acre.

William Seward.

Popular opinion was that Alaska was a worthless icebox, and many called the purchase "Seward's Folly." It was known that Russia hadn't done anything with Alaska except hunt for furs. In recent years, Russia had run up a debt of $500,000, trying to make the colony profitable. On top of all this, the Tsar remembered the California gold rush from a generation earlier, and how it had happened just after Russia sold its outpost in California; he feared that if gold was found in Alaska, the Russians would not be able to hold on to the territory, so they might as well sell out before they were thrown out. Sure enough, gold was found along the Klondike River thirty years later; technically that was in Canada, but it was close enough to the border that the prospectors passed through Alaska to get there, and some of them chose to stop and try their luck digging and panning in Alaska, rather than go all the way to the Klondike.

Seward didn't stop with Alaska. During the Civil War he revived the idea that the US should annex Canada. President Lincoln was opposed to this, feeling it would lead to war with Britain, and told Seward, "One war at a time." In the same year as the Alaska Purchase (1867) the United States annexed two coral atolls that had been discovered in the middle of the Pacific eight years earlier. These were named the Midway Islands, and this was the first step toward annexing the nearest archipelago, Hawaii. Seward also proposed that the United States acquire Hawaii, the Dominican Republic and the Virgin Islands (then called the Danish West Indies), and suggested that a canal across Central America and a worldwide telegraph network would make the world a better place. Nobody else was ready for these plans, though, showing that Seward was at least a generation ahead of his time.

Meanwhile in California, San Francisco became the home to the nation's only emperor. This was Joshua Abraham Norton, a Jewish immigrant who had formerly lived in Great Britain and South Africa. Coming to California during the gold rush, he earned a fortune of $250,000 over the next three years, by trading real estate and selling supplies to miners. Then he gambled it all on an attempt to corner the rice market, by buying up all the rice he could find in San Francisco, thus driving up the price from four to thirty-six cents a pound, only to be ruined when several shiploads of rice arrived from Peru and brought the price down again. Losing all that money seems to have made him go insane, because he left town for a while, and when he came back, in 1859, he visited the editor of the San Francisco Bulletin with an official-looking document that proclaimed him "Norton I, Emperor of the United States and Protector of Mexico."

Norton's proclamations as "emperor" were to suspend the Constitution, dissolve Congress and all political parties, have paper money printed with his picture on the bills, and get loans worth several million dollars from major banks (he was surprised when the banks refused). When the Central Pacific Railroad refused to give him a free meal, he abolished it. Normally such a madman would have been put away in an asylum, but incredibly, the people of San Francisco decided he was harmless, and chose to play along with his game. For the next twenty-one years they treated him as if he was their emperor.

Emperor Norton held court in a shabby, one-room apartment that rented for fifty cents a day. When he went out, wearing a second-hand officer's uniform that made him look like Napoleon III, with a tall, plumed hat and beat-up cavalry saber, the people he met bowed and curtsied. When he ate out in an expensive restaurant, he was seldom presented with a bill, nor did he have to pay to ride public transportation or go to the theater. A seat was also reserved for him at city council meetings. He did not pay attention to the government in Washington until Ulysses Grant was president (see the next section), and then he sent a letter saying that Grant could stay in office if he would handle the nation's day-to-day affairs. In other words, he seemed to think that Grant was his prime minister!

Emperor Norton spent most of his time inspecting the streets, looking for ways to improve the city's infrastructure, like building a suspension bridge across the bay to Oakland (that was finally done in the 1930s, see footnote #101). One day while doing this, he came upon an anti-Chinese riot, and he broke it up by positioning himself between the rioters and the Chinese immigrants, bowing his head, and saying the Lord's Prayer until the rioters went away. It was also on the streets where he collapsed and died in 1880; a crowd estimated at 10,000-30,000 attended his funeral.

Grant and the Beginning of the Grand Old Party Era

The period covered by this chapter was the golden age of the Republican Party. Although American politics remained a two-party system, of the fifteen presidents that served during this time, twelve of them were Republicans (the three exceptions were Johnson, Cleveland and Wilson). Most people came to assume that the natural order was to have a Republican in the White House, regardless of which party controlled Congress. And when the Republicans became the majority party in the North, it did not matter much which way the South and West voted, because the North had the bulk of the nation's population; by contrast, the Democrats had to secure a commanding lead in both the South and the North to win elections.

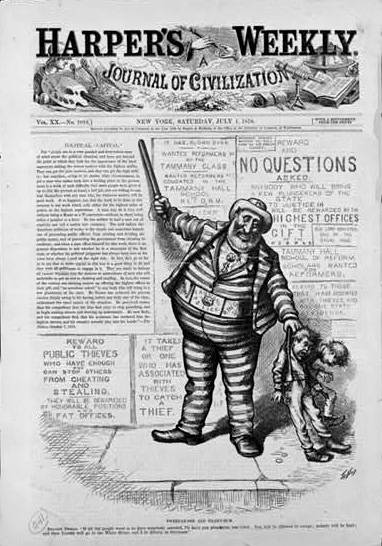

The original Republican elephant (322 KB, will open in a separate window).

Thomas Nast (1840-1902) was the greatest cartoonist in American history. In Chapter 3 we noted that he publicized the donkey as the Democratic Party's symbol. He created the Republican elephant as well. A Republican to the core, Nast wanted his party's symbol to be strong but loveable at the same time; the elephant fit that role perfectly. Click on the above link to see Nast's first use of the elephant, drawn in 1874. In this complicated cartoon, we see a Democratic paper, the New York Herald, as a donkey wearing a lion's skin, scaring off the other animals, while the Republican elephant walks into a trap made from the problems of the Grant years.

But back to the narrative. The 1868 presidential election was noisier than most, because Union veterans participated enthusiastically. This time the Republican candidate was their general, Ulysses Grant, and the "Boys in Blue" staged parades and rallies on his behalf, campaigning on the slogan "Vote as you shot!" By comparison the Democratic candidate, former New York Governor Horatio Seymour, was colorless. The election also showed how different popular and electoral results can be; Grant won an overwhelming victory in the Electoral College, at 214 to 80. But the popular vote was much closer, where Grant won by 3 million to 2.7 million. It was 700,000 blacks voting for the first time that decided the election in Grant's favor.

We noted earlier (in footnote #11) that Grant became a soldier because that was the only profession he was good at. He had no grudge against the South, but only wanted to serve his country and earn a living at the same time. Thus, he probably should have stayed in the military, instead of going to the White House. As president, he had two failings that made his administration terribly corrupt. First, he and his wife liked expensive presents, and freely accepted them without thinking much about what the givers might want in return. Because he never had much money himself, Grant was awed by those who could earn large amounts of wealth with little effort. Second, he gave out too many government jobs to friends and family. These folks, and the Wall Street thieves he called friends, got away with stealing millions from the government because Grant could not believe that anyone he liked was dishonest.

One of the biggest opportunities for corruption was in the railroad industry, because railroad building in America peaked during the Grant years. The first nation to build a railroad network, Great Britain, did it through private investment, but North America was so much larger that folks did not think the same thing could be done here; hence, the government was involved from the start. By 1870, the United States had 53,000 miles of railroad tracks, compared with 65,000 miles of tracks in all of Europe.

In Chapter 3, we saw how starting the first transcontinental railroad from either a Northern or Southern state became a hot political issue. After the South seceded, however, there was no longer anything to keep Northern congressmen from starting the railroad in Union territory; Congress authorized construction to begin in 1862.(39) The Union Pacific Railroad was organized to manage the eastern terminus (Omaha, NE), while four California entrepreneurs founded the Central Pacific Railroad at the other end (Sacramento, CA). From Omaha and Sacramento, the plan was to have the two railroads build tracks toward each other until they met in the middle.

The government subsidized the railroads by paying them according to how many miles of track were laid, and offered low-interest loans when they were building in the mountains. This encouraged the railroads to build inefficiently; the tracks rarely ran in a straight line, and they tended to follow the most rugged path possible.(40) After the railroad was finished, shoddy workmanship was found in several places where the builders were in a hurry to get done, meaning that repair and rerouting had to be done over the next few years. In addition, an incredible amount of public land was given to the railroads as land grants: 242,000 square miles. As historian Paul Johnson explains it, "The rails got one-fourth of the states of Minnesota and Washington, one-fifth of Wisconsin, Iowa, Kansas, North Dakota, and Montana, one-seventh of Nebraska, one-eighth of California, and one-ninth of Louisiana." Of course the railroads didn't need that much land for tracks and stations, and what they didn't use was sold to settlers. This gave the railroads future customers, because the settlers would naturally find the railroads to be the most convenient way to transport freight and passengers.

On top of all that were the shady billing practices of the Union Pacific. Instead of actually building the track itself, Union Pacific hired a construction firm, Crédit Mobilier, to do the job. In the course of doing so, Crédit Mobilier charged the government $94 million for work that cost $44 million. What made the practice really crooked was that by this time, the Union Pacific was a front; Crédit Mobilier executives bought up Union Pacific stock until the same people were in charge of both companies. They managed to keep the scandal secret until 1872, by bribing several congressmen with Crédit Mobilier stock. The list of figures later accused of taking the stock included Ohio's James A. Garfield, Maine's James G. Blaine, and both of Grant's vice-presidents, Schuyler Colfax and Henry Wilson.

Finally, construction of the Union Pacific was threatened by Indians and slowed by buffalo herds, and there were race riots as the two railroad crews approached each other, because the Union Pacific workers were mostly war veterans and Irish immigrants, while the Central Pacific mainly used Chinese labor. Nevertheless, there was cause for celebration when the tracks met. This happened at Promontory Point, UT on May 10, 1869; for the last piece of track, twelve silver spikes, followed by one golden spike, were driven in, and two locomotives came from opposite directions until they touched, symbolizing the "wedding of the rails." Rapid travel across the continent, from coast to coast, was now a reality.(41)

Meanwhile in New York, two speculators threatened the national economy with their schemes. Jay Gould and James Fisk were young men who, like the sons of Thomas Mellon (see footnote #23), spent the early 1860s learning how to make money, instead of fighting in the Civil War. Gould started by taking control of a leather factory, and then got involved in banking and the trading of railroad stocks. Fisk ran away from home at the age of 16 to join the circus, later worked as a hotel waiter and a peddler, and finally made his fortune by smuggling cotton across enemy lines during the war. In 1867 Daniel Drew, a successful financier, put Gould and Fisk in charge of the Erie Railroad, to keep it out of the hands of Cornelius Vanderbilt (see Chapter 3, footnote #68), the richest man in America. Gould and Fisk did it through an alliance with Boss Tweed (see below), whom they also made a director, and by printing one hundred thousand shares of illegal Erie stock. Vanderbilt kept buying up the stock in the hope of gaining control over the railroad, without knowing the shares were really worthless, and Fisk remarked, "If this printing press doesn't break down, I'll be damned if I don't give the old hog all he wants of Erie!" When Vanderbilt found out he had been swindled, and called for their arrest, Gould and Fisk had to flee the authorities, taking a ferry to New Jersey with the Erie books and $6 million in cash. Then Gould went to Albany and bribed the state legislature into legalizing all the stock Vanderbilt had bought, plus a lot more (so that Vanderbilt still would not have control of the company). Finally Vanderbilt conceded defeat in what was now called the "Erie War," and settled with Gould for $1 million.

After the "Erie War," Gould and Fisk tried to corner the gold market. The idea here was to buy as much of the $15 million worth of gold in circulation as possible, wait for the price of gold to go up, and then sell it for a profit. They were counting on Grant to keep gold in short supply, because he was determined to restore US currency to its pre-Civil War standard (this would lead to a spell of deflation, after the Gold Standard was officially adopted in 1873). Gould bribed the president's brother-in-law to act as a spy and advise Grant not to release any gold reserves, while Fisk, knowing the president's weaknesses, met Grant in person, calling himself "Admiral" of the Fall River steamship line, and dressing like a real admiral. This time, however, the president refused to play the game, and had the government sell $4 million in gold when he saw what was happening. Gould and Fisk found out about the government gold just in time to sell their stakes at a profit, though it meant betraying their partners.(42)

To an outside observer in the late 1860s and 1870s, it must have seemed that corruption had become the national pastime. State governments were corrupt, in both the booming North and the "reconstructed" South. The District of Columbia government, both houses of Congress, the War Department, and the Treasury all took part in stealing and graft. Grant's first Secretary of State, Elihu B. Washburne, only stayed in that job for twelve days, so he could call himself a former Cabinet member when he got the job he really wanted, minister to France. The Secretary of the Navy made $320,000 from profits on railroad contracts, while the Secretary of War took bribes worth $25,000 from Indian post storekeepers. Grant's minister to Brazil showed he was different from the rest by stealing $100,000 from the Brazilian government, instead of the US. Even Orville Babcock, a Civil War general and Grant's secretary since 1864, was involved in the Whiskey Ring, a scheme that took at least $3 million from federal taxes on liquor.

But all the activities of Wall Street barons and crooked Washington politicians looked like chicken stealing, compared with what Tammany Hall, the Democratic Party machine in New York City (see Chapter 3, footnote #21), made off with. Led by William M. Tweed, a former city alderman and congressman, a handful of Tammany insiders stole between $30 and $200 million (the exact amount was never discovered) between 1865 and 1871. Consequently, New York City's debts increased from $36 million in 1868 to about $136 million by 1870, without paperwork or visible construction to show where the money went. Tweed bribed the governor, state legislature, mayor, and numerous other officials to get them on his side, and demanded bribes/kickbacks in return from anyone who wanted a contract with the New York government, or who wanted to run for public office. Any city employee who opposed Tweed would soon find himself out of a job. Observers estimated that in the 1868 elections, at least one-sixth of the votes from New York City were fraudulent (Tweed said, "I don't care who does the electing, so long as I get to do the nominating."). When anyone complained about these practices, Tweed didn't bother to cover up, and boldly asked, "What are you going to do about it?"

Most of the stealing came from Tweed's contractors, who made unnecessary repairs, presented the city with bills for their work that typically charged 15 to 65 percent more than the projects on actually cost, and handed the excess cash to the Tweed Ring. The worst examples were as follows:

- $13 million for a courthouse that was supposed to cost $3 million.

- $3 million for city printing, stationery and advertising over a two-year period.