| The Xenophile Historian |

|

The Anglo-American Adventure

Chapter 5: Pax Americana, Part II

1933 to 2008

This paper is divided into five parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| First, an Explanation of the Title | |

| The New Deal | |

| New Deal II | |

| Getting Out of the Depression--The Hard Way | |

| The Gathering Storm | |

| Pearl Harbor | |

| World War II |

Part II

| The Country Boy From Missouri | |

| Enter the Cold War | |

| China, Korea, and the Pumpkin Papers | |

| "I Like Ike" | |

| Life in the 1950s | |

| Go to Page Navigator |

Part III

| The "New Frontier" | |

| Who Really Killed JFK? | |

| The "Great Society" | |

| Nixon Returns | |

| "All the President's Men" |

Part IV

| Years of "Malaise" | |

| The Reagan Renaissance | |

| George Bush the Elder | |

| Clintonism |

Part V

| The Clinton Scandals | |

| Islamism on the Move | |

| The Battle of the Ballots | |

| George Bush the Younger | |

| Angry Democrats, Drifting Republicans | |

| Modern American Demographics | |

The Country Boy From Missouri

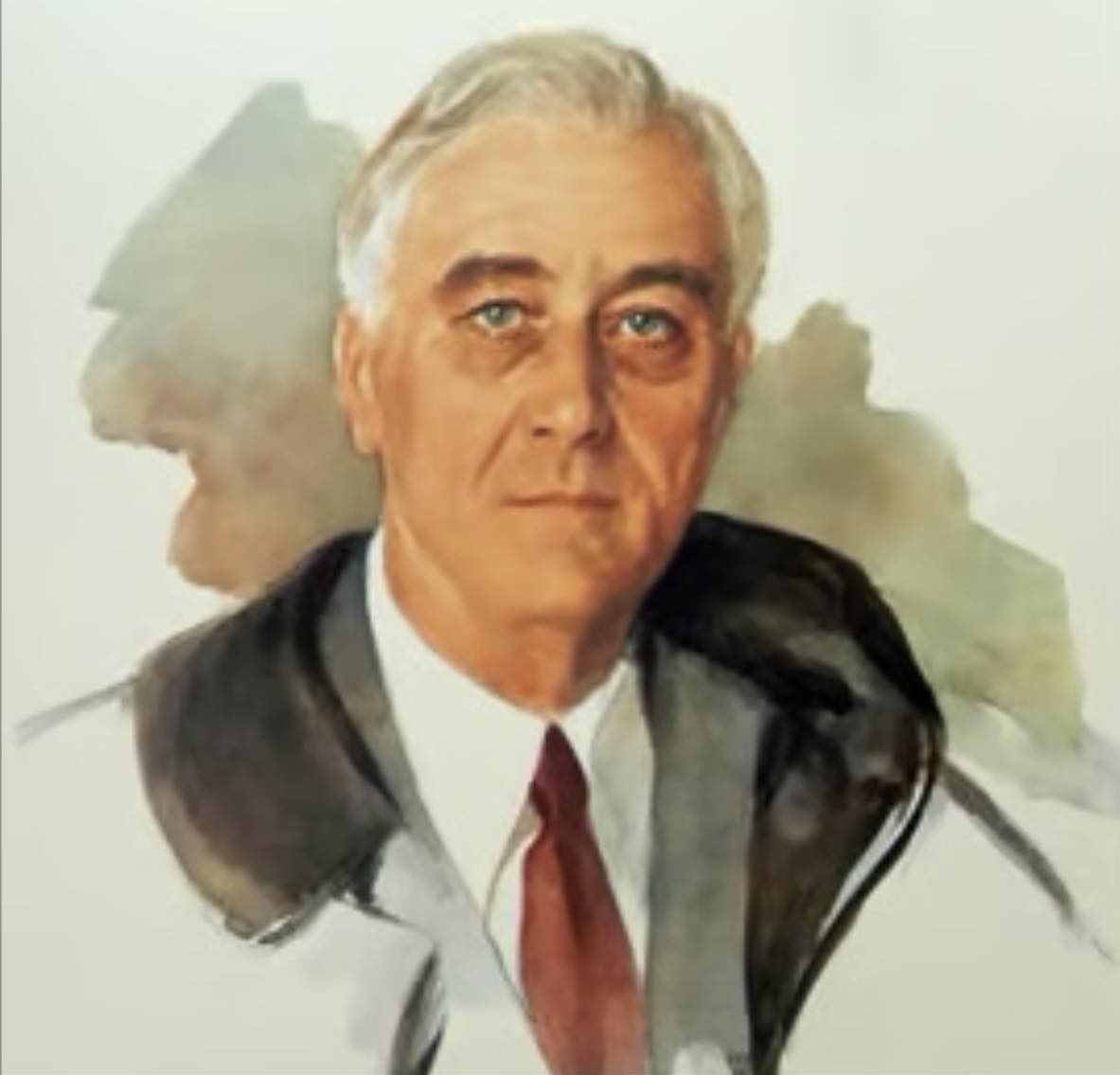

Roosevelt was definitely "the sick man of Yalta." During that conference, Winston Churchill's physician observed that Roosevelt looked like he was suffering from hardening of the arteries in the brain, and predicted that he had only a few months to live. At the end of March, FDR went to his vacation home at Warm Springs, Georgia, to rest up before appearing at the first session of the United Nations. However, he never got to see his last dream--the creation of a future world government that would put an end to all wars. On April 12, 1945, while posing for a portrait, he said, "I have a terrific headache," and slumped forward. Two and a half hours later he died from a cerebral hemorrhage.(18)

The "Unfinished Portrait."

In the weeks after Yalta, Roosevelt had grown disillusioned with Stalin; the Soviet leader was not keeping the promises he had made to allow the establishment of democratic governments in eastern Europe, especially in Poland. This was one of the first signs that after the war, the Allies would not live happily ever after.(19) On the day of Roosevelt's death, American forces were fifty-seven miles from Berlin, and the Russians were just thirty miles away, so he knew victory would come soon. Sure enough, Germany surrendered less than a month later, on May 8, 1945, and the Allies celebrated V-E Day (Victory in Europe Day).

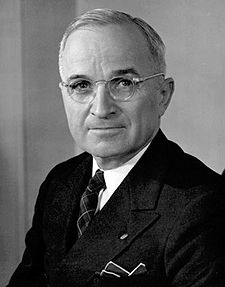

If FDR proved that a person could be president for life, Harry S. Truman proved that anyone can become president. As a boy, he wanted to go to West Point, but was turned down by the academy because he wore glasses. Over the next few years he worked as a railroad timekeeper, mail clerk, bank clerk, bookkeeper, and a farmer. Then came World War I, and he got the military record he wanted, as an artillery captain in the Missouri National Guard. After the war he opened a haberdashery in Kansas City, but it failed during the recession of 1921. By that time, though, he had gotten to know Tom Pendergast, the boss of the Democratic Party in Kansas City, and in 1922 Pendergast provided a new career for Truman, by getting him elected judge of the county court in Missouri's Jackson County. Although he wasn't expected to act like a mayor in that job, he succeeded in reducing the county debt from $1 million to $600,000, and repaired some old roads and buildings. He failed to win re-election in 1924, but successfully ran for the office of presiding judge of the same court, getting elected in 1926 and 1930. While in this job he found out that the best-designed courthouse in the nation was in Shreveport, LA, so he hired its architect to design a courthouse like it for Kansas City, and floated a bond issue to pay for it.

Although Truman was honest and fair to the taxpayers, Pendergast ran a classic political machine; when Truman did well, it benefited him, too. Because other Pendergast associates were outright gangsters, involved with bootlegging, gambling, prostitution, graft and murder, this led to an investigation by Washington, but nobody thought Truman had committed any crime, so this was only a minor interruption to his work. When his second term as presiding judge ended in 1934, he wasn't allowed to run for a third term, and Pendergast asked him to run for the Senate. He won, and went to Washington as an enthusiastic supporter of the New Deal. However, Roosevelt disliked Pendergast, so he supported one of Truman's opponents when he ran for re-election in 1940. Truman's response was to travel around Missouri and tell the voters about his record, in simple language that anyone could understand. The result was a victory so unexpected that the Senate gave him a standing ovation when he returned. During his second term he got national attention by leading a committee that investigated waste in military spending, and this committee was credited with saving $15 billion in government funds. That was the situation when he was picked in 1944 to be the next vice president.

Harry S. Truman.

Vice President Truman was visiting Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn's office when the news from Warm Springs reached him.(20) He was sworn in as president the next day, after his family, members of Congress and the Cabinet, and the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, could all be brought to the White House. After he took the oath of office, Truman told reporters, "Boys, if you ever pray, pray for me now. I don't know if you fellas ever had a load of hay fall on you, but when they told me what happened yesterday, I felt like the moon, the stars, and all the planets had fallen on me." He had only been vice president for 82 days, and during that time was largely ignored by Roosevelt; they had seen little of each other, and Roosevelt never instructed Truman on how he conducted the war, or his plans for peace. Thus, Truman was thrown unprepared into the world's most complicated job (Roosevelt's daughter had to help brief him). At the time little was expected of Truman, because he wasn't a cultured aristocrat like his predecessor, but because he faced some really tough decisions, and did not shy away from making them, he now usually appears on lists of the best presidents in US history.(21)

One of the first tough decisions was how to finish the war, because with V-E Day, it was only half over. Most observers expected a victory against Japan would follow, but the battle of Okinawa, which cost 12,000 American and an estimated 100,000 Japanese lives, showed that it would not come easy. Plans were drawn up for a two-step invasion of Japan, first with landings on the islands of Kyushu and Shikoku in November 1945 ("Operation Olympic"), followed by landings on the main island, Honshu, in March 1946 ("Operation Coronet"). Because the Japanese were likely to defend their homeland with everything they had, a minimum of one million American, British and Japanese casualties was predicted.

By the way, everyone in the armed forces was so sure a bloodbath was about to begin in Japan, that the government minted half a million Purple Heart medals, to give to those wounded and killed in action. Because the invasion didn't happen, the Purple Hearts weren't needed, so they were saved for soldiers earning them in future wars: Korea, Vietnam, Kuwait, Afghanistan, Iraq, etc. It wasn't until 2000 that the supply began to run low and the government decided to make more; even so, rumor has it that more than 100,000 World War II-era Purple Hearts were never awarded, and are still in stock, ready for use.

What Truman did not know until now was that a shortcut solution was available. In 1939 Albert Einstein, the famous physicist and a recent immigrant from Germany, sent Roosevelt letters urging him to form a research team to build a nuclear weapon, before Hitler's scientists did it first. The team was duly assembled, and over the next six years the "Manhattan Project" conducted research both secretly and steadily. One member of the team, Enrico Fermi, successfully built the first nuclear reactor in 1942, at the University of Chicago. The product of their efforts, an atomic bomb, was exploded in a test near Alamogordo, NM, on July 16, 1945.

Meanwhile, one more conference of the "Big Three" took place, at Potsdam, Germany. They reached agreement on where the postwar frontiers of Germany and Poland should be, but otherwise this meeting wasn't as successful as those at Tehran and Yalta. The main reason was a cooling of relations between the Soviet Union and its wartime allies; Stalin was determined to have as much of eastern Europe as possible for himself, and to that end, he wouldn't allow anyone but communists to liberate all countries north of Greece and east of Austria. Consequently, there would be no big treaty announcing that World War II was over, no genuine peace in the postwar world. Long after Potsdam, Truman wrote in his memoirs about the decision he quietly made there: "I made up my mind that I would not allow the Russians any part in the control of Japan . . . The Russians were after world conquest."

Part of the problem was that personalities no longer meshed; the Allied leaders didn't get along as well as they did when Roosevelt was alive. Truman took an immediate liking to Churchill, but in the middle of the conference, British elections replaced Churchill with his rival, Clement Attlee, as prime minister. Truman and Attlee continued the special relationship between the United States and Great Britain, but the friendship that Roosevelt and Churchill had wasn't there. As for Stalin, Truman remarked that the Soviet leader reminded him too much of Tom Pendergast. Finally, it was at Potsdam that Truman learned the Alamogordo nuclear test had been a success.

Source: http://history.state.gov/

Two more atomic bombs were built, and Truman gave the order to use them. One was dropped on the city of Hiroshima on August 6, and the other was dropped on Nagasaki three days later. The results were devastating; estimates put the number of dead at 140,000 in Hiroshima and 80,000 in Nagasaki, half in the initial blast, and the rest from burns and radiation sickness later on. Still, the body count was far less than the alternative mentioned previously. On August 14, Emperor Hirohito called on Japan to surrender, and the terms of surrender were signed on an American battleship, the USS Missouri, on September 2, 1945. World War II was finally ended.

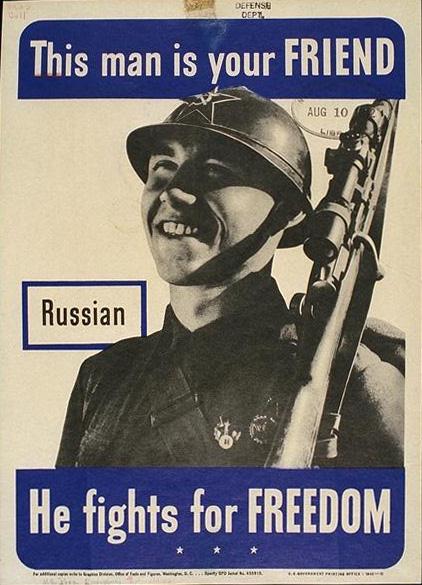

Enter the Cold War

The end of the war did not make Truman's burden lighter. With the old world order shattered, he found it would be his responsibility to define what would take its place. Along that line, he allowed the United Nations to hold its first meeting on schedule, two weeks after FDR's death.(22) But both the UN and peace depended on the Allies cooperating after the war, and Stalin was now showing that his plan for a postwar world was not what Western leaders had in mind. At first Truman, like Roosevelt, tried to placate Stalin; the most notorious example of this was "Operation Keelhaul" in which as many as a million displaced Soviet citizens/refugees were returned to the USSR, though most of those going back could only expect concentration camps, exile and executions. Only gradually did Truman realize that Stalin had no intention of honoring most of the agreements he had made. By then most of eastern Europe had fallen under Soviet control, the civil war in China between Chiang Kai-shek's nationalists and Mao Zedong's communists had resumed, and communists were making inroads into other areas, like Iran, Korea, France and Italy. It also became clear that the United States could not completely demobilize and go back to the blissful ignorance that characterized it in the isolationist years before the war. Somebody would have to act as the "world's policeman" to prevent losing the rest of it to communism, and the United States was the only nation strong enough to do it.(23) For the first time, US troops would have to be active overseas in a time of peace.

Unlike previous foreign problems, the US-Soviet rivalry was not something that Americans could either ignore or settle quickly. Bernard Baruch, a speculator and political advisor, coined an appropriate name for the standoff: "Let us not deceive ourselves, we are in the midst of a cold war." He called this the "Cold War" because it broke men's wills more often than their bodies. Only in China (and later Korea) was it a conventional shooting war; elsewhere the communists were guerrillas who didn't wear uniforms or carry banners. Or they might be spies and politicians, who caused confusion in the countries they wanted to subvert. In eastern Europe hundreds of thousands of Russian soldiers patrolled the polling places when the first postwar elections were held, ensuring that their candidates would win, or in the case of Czechoslovakia, used blackmail, the threat of invasion, and one "suicide" (the Czech president fell out of a window) to take over. The Cold War did not make much sense to Westerners, so while the West eventually learned how to fight, there were some spectacular failures (e.g., Vietnam and Cuba) to match the successes (e.g., Greece, Malaysia, Germany). In the end the West won because it had a stronger economy and did more to improve the lives of people worldwide; the Soviets couldn't match this, even when Nikita Khrushchev and Mikhail Gorbachev loosened controls on the Soviet economy. And while neither side was a perfect angel, the errors made by the Western nations were far less damaging--no environmental damage on the scale of Chernobyl, no famine like China's "Great Leap Forward," and no massacres like the Pol Pot terror in Cambodia. Still, the Cold War would last more than forty years, and end up costing more than World War II.

The Cold War's main theater was Europe; the former headquarters of Western civilization was now divided between a communist east and a capitalist west. The division was so dramatic, that Winston Churchill called it an "iron curtain" in a 1946 speech, and the name stuck. The United States began rushing aid to western Europe to rebuild its economy (the "Marshall Plan") before the people of those countries got the idea that communism might give them a better future. On the front line against communism, emergency aid was also the answer; supplies were airlifted into West Berlin to keep it from starving when the Soviets blockaded the part of the city they did not control, and $400 million was sent to the governments of Greece and Turkey, allowing them to successfully fight communism. The last action was soon known as the "Truman Doctrine": the United States would draw a line across Europe, and do whatever was necessary to keep communism from crossing that line to infiltrate, corrupt, and take over any more countries.

On the home front, Americans saw a step back from the activism that had marked the Roosevelt years. This was the right thing to do, because the public was in a conservative mood, and didn't want another wave of changes like they had seen under the New Deal and World War II. Businesses and labor had to be retooled and retrained so there wouldn't be a rise in unemployment after US servicemen came home. Moreover, Americans had accumulated $140 billion in savings during the war, because there were few houses, cars and luxuries to spend them on, and they wanted more consumer goods now; government controls had to be relaxed to allow the free market to meet this demand. Consequently, for the first time since the 1920s, Americans could prosper again.(24) In an attempt to continue what FDR had started, Truman introduced a nationalized health care plan, but the Republicans managed to blame everything going wrong in the world on the current administration, and by repeating the slogans "To err is Truman" and "Had enough?", they got a Republican Congress elected in 1946; this kept the health care plan from going anywhere.

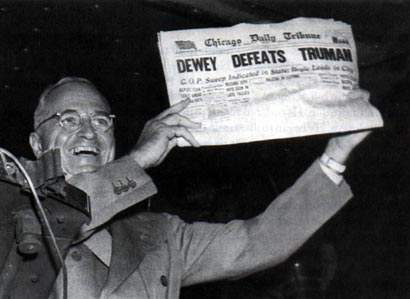

The 1948 presidential election was the biggest electoral upset in American history, because the polls predicted that Truman would not be reelected. Voters were mad at rising prices, meat and housing shortages, and growing Cold War tensions. The Republicans nominated Thomas Dewey again, and polltakers like George Gallup declared he was more popular than Truman. In addition, the Democrats were divided three ways. Former vice president Henry Wallace, who had been a strong opponent of Truman's anticommunist policies, formed a new Progressive Party (no connection with the Progressives of 1912 and 1924) and ran as its candidate, taking away the left wing of the Democratic Party.

A similar split took away the right wing of the Democratic Party. This time the issue was civil rights. Black Americans had done their part to win the war, by becoming factory workers, soldiers, sailors, and even pilots (the Tuskegee Airmen), so calls were now going forth to stop treating them as second-class citizens. The color barrier in sports had also been broken, when Jackie Robinson became the first black major-league baseball player (1947). Consequently, at the 1948 Democratic convention, several northern liberals, led by Minneapolis Mayor Hubert Humphrey, added a civil rights proposal to the Democratic platform, in the hope that it would win over the black vote (until now, blacks had usually voted Republican). Truman agreed to it; in July he signed Executive Order 9981, which called for racial desegregation of the armed forces. However, the Southern Democrats would not support such a platform, and many of them walked out of the Democratic convention. They ended up forming another third party, the States' Rights Democratic Party (also called the Dixiecrats), with South Carolina Governor Strom Thurmond as their candidate. Truman partially offset the Southern defection by choosing another Southerner, Kentucky Senator Alben Barkley, as his running mate, but still he had little besides the middle faction of his own party, and since Dewey was also seen as a moderate, he couldn't count on even holding onto that.

Because Truman and Dewey took similar stands on the issues, the 1948 campaign became a personality contest: the polite Dewey against the scrappy Truman. Ignoring the polls, Truman said, "I'm going to give 'em hell," and went on what would be known as the "Whistlestop Campaign." This was the same style of campaigning that he had used as a senator, only now it would be done across the nation. In September and October he traveled 22,000 miles by train, and at every stop he made a fiery speech, attacking Dewey and the "do-nothing Republican Eightieth Congress." Dewey also used a train, but his campaign was passionless by comparison. He felt that victory was in the bag as long as he didn't do anything stupid, so instead of responding to Truman's attacks, he spoke in meaningless generalities ("You know that your future is still ahead of you.").

As it turned out, the polltakers completely missed those voters who enjoyed the fight Truman put up. Thus, when the first vote counts showed Truman ahead, it was dismissed as a fluke; the media spent most of Election Night explaining that Dewey would catch up and pass Truman, once the rest of the votes were in. The splits within the Democratic Party were overrated, too; Thurmond and Wallace each got only 2.4 percent of the popular vote. Wallace didn't win any states, but he took enough votes to keep Truman from winning in New York, while Thurmond won four southern states and thirty-nine electoral votes, because his support was concentrated in the South.(25) Truman himself beat Dewey by more than two million popular votes, and got 303 electoral votes to Dewey's 189.

For his second term, Truman offered a program called the "Fair Deal," which was simply a warmed-over New Deal package, designed to help labor and farmers the most. For this he reintroduced the call for universal health care, and proposed more civil rights legislation, federal funds to build housing, an expansion of Social Security to cover more senior citizens, and repeal of the Taft-Hartley Act (a law limiting the activities of labor unions, which was passed over his veto in 1947). Although the Democrats had regained control of Congress in the 1948 election, they were cool to these proposals; they voted down universal health care for the second time, left the Taft-Hartley Act alone, and only passed the housing bill. Truman settled for this, because he felt that it was more important to finish the year with a budget surplus, in order to pay down the national debt accumulated under Roosevelt, and he couldn't do that if spending increased too fast. Indeed, when the economy experienced a mild recession in 1949, Truman chose to let it recover naturally, rather than have the federal government intervene again.(26) But he did have his way with another idea, the Point Four Program, which was a plan to provide advanced skills, knowledge, equipment and private investment to poor nations, much like the Peace Corps would do later on.

China, Korea, and the Pumpkin Papers

In 1949 the United States followed up on its previous Cold War activities with two more that were critical in shaping modern-day Europe:

1. The sectors of Germany occupied by the United States, Britain and France, including West Berlin, were merged to create a postwar German state, the Federal Republic of Germany (also called West Germany). Meanwhile, the Soviets turned their sector of Germany into the German Democratic Republic, East Germany for short.

2. The formation of a permanent alliance between the United States, Canada, and most of western Europe--the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Other alliances and blocs sprang up afterwards, some pro-Western, some pro-Soviet, and some neutral, but NATO was the most successful.

However, 1949 was far from being a good year for the Americans. First, the USSR exploded its first atomic bomb that year, ending the nuclear monopoly that the US had enjoyed during Truman's first term. This meant that any future war between the Americans and the Soviets ran the risk of turning into a nuclear holocaust. Second, in China the Communists triumphed over the Nationalists. Though the Americans had given lots of money, arms and advice to the Nationalists, the way they had done for western Europe, the Nationalists were so unpopular and inefficient that the aid simply slipped out of their hands. Over the course of 1949, one city after another fell to the Communists, and the end of the year saw Chiang Kai-shek and his followers flee to the island of Taiwan. Mao Zedong's takeover ended the century and a half when China was backward and weak, a "paper dragon." Now he would use China's almost unlimited manpower to stage a rapid recovery, giving the Soviets a strong ally to use in dominating Asia. Back in the United States, many Americans felt an emotional tie to China, because they had supported missionary activities there(27), and before long conservatives would be looking for someone to blame, asking the "Who lost China?" question. Truman tried to prevent a future war in China by telling Chiang to forget about trying to reconquer the mainland, and conservative Americans responded with calls to "Unleash Chiang Kai-shek."

Compared with Truman's successful containment policy in Europe, his support for Asian allies seemed too little and too late. Now that a communist China existed, communist guerrillas in other parts of Asia, like the Viet Minh in Vietnam, had a powerful base for support and training. Even more immediate, Mao's victory would make a big difference in the Korean peninsula. A Japanese colony before 1945, Korea had been divided at the end of World War II, with Russian soldiers occupying everything north of the 38th parallel and American soldiers occupying everything south of that line. The result was the same as what happened in Germany; when Washington and Moscow could not reach an agreement on what kind of government a united, independent Korea should have, the Americans set up a pro-Western regime in Seoul and the Soviets set up a communist one in Pyongyang. After that, Korea was usually an afterthought to foreign leaders; for some reason, South Korea was not mentioned when Dean Acheson, Truman's Secretary of State, made a speech listing the places the United States would defend in Asia and the Pacific. Because of this, and because American forces had been withdrawn from South Korea in early 1950, the North Korean leader, Kim Il Sung, got the idea that if he struck quickly, he could conquer South Korea and get away with it.

On June 25, 1950, communist planes struck targets south of the 38th parallel; like Pearl Harbor, this sneak attack came at dawn on a Sunday morning. Then Russian-built tanks led the way, as the North Korean "People's Army" began an all-out invasion of South Korea. President Truman responded quickly; he ordered General MacArthur to give air support to the South Koreans from Japan, and rushed the US Seventh Fleet from the Philippines to the strait between Taiwan and the Chinese mainland. Then he pressured the United Nations to act, and not only did it vote sanctions against North Korea, it called on all UN member nations to repel the invasion.(28)

Next, Truman asked Congress to authorize the sending of US troops to Korea. He got that request, but in doing so, set a precedent that increased the power of the federal government's executive branch significantly. First, he did not ask Congress to declare war, because he felt this was just a "police action" authorized by the United Nations. Thirty years earlier, opponents of the League of Nations had warned this could happen; they didn't want Americans going to war because some international organization sent them. Moreover, Truman said he would send the troops anyway, whether or not the UN authorized it. The result is that although the Constitution gave Congress the power to declare war, Congress has not issued a war declaration since 1941; instead the president just asks Congress to approve and fund any military activities. Thus, from a legal standpoint, the Korean War was a war in everything but name. Truman's action to save South Korea was justified--today South Korea is one of the world's most advanced, most successful nations--so you can say he did the right thing, but in the wrong way. This may also explain why some Americans see World War II as the last "good war"; not only was there a formal declaration, it was fought with conventional forces on both sides, and the enemy was obviously evil, which hasn't been the case with some of the wars fought since then.

The first ninety days of the Korean War saw US and UN forces defending Pusan, the last South Korean port that had not fallen to the communists. In September MacArthur had enough troops and equipment to stage the most brilliant maneuver of his career, the Inchon landing, which was quickly followed by the liberation of Seoul. By then the rest of the force had broken out of the Pusan perimeter and chased the North Koreans back across the 38th parallel, so now the question was whether to declare the "police action" finished, or launch a counter-invasion of North Korea. MacArthur and Truman decided on the latter, to teach the communists a lesson, but as they approached the China-Korea border, MacArthur rashly started bombing targets in northern China, and the Chinese sent a horde of soldiers to fight on North Korea's side. The size and ferocity of the Chinese offensive threw the Western coalition south and briefly captured Seoul again. Eventually China committed 850,000 men against 700,000 UN troops (mostly Americans and South Koreans, plus smaller units from other nations). By the spring of 1951 the front line of the war was back in the middle of the peninsula, not far from where the war began. There both sides dug in and fought in a brutal stalemate that lasted for more than two years.

At first, MacArthur had promised the troops would be home by Christmas, and when the Chinese prevented that, he demanded an all-out war against China. Truman had to relieve him from command, to keep the Korean War from turning into World War III.(29) Dismissing a general for insubordination was the reasonable thing to do, but most Americans remembered MacArthur as a hero from the previous war, so the decision was one of the most unpopular a president has had to make; he faced calls for impeachment from the Chicago Tribune and Senator Robert Taft. Because of that, and because the war had gone sour, Truman's approval rating in public opinion polls dropped to 22 percent in February 1952, the lowest rating any president has ever received.(30)

Not only was Truman surprised at communist betrayals of peace agreements, he had trouble believing that Americans might actually be Soviet spies. As another Democrat, New York Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, explained in 1997, "President Truman was almost willfully obtuse as regards American Communism. In part this was a kind of regionalism in an era before television and airlines produced a much more homogeneous polity. There were no Communists in Kansas City politics. Communists were in New York City, and these places were far apart. . . . No person active in New York City politics of the 1930s could have failed to know Communists, or know of them. But in Kansas City and Washington, D.C., it was quite possible to see the 'Communist conspiracy' as a Chamber of Commerce plot."(31) It also didn't help that General Bradley (see footnote #29) decided to withhold from him knowledge that Soviet spy networks had been exposed through the decryption of wartime cable traffic. This network had even penetrated the Manhattan Project, which was revealed when two spies, Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, were arrested on a charge of stealing nuclear secrets for the USSR. Convicted in 1951, they were sent to the electric chair two years later, a controversial sentence because of questions over how active a role Ethel played in the caper.

Fortunately for Truman, the government apparatus for catching spies and un-Americans had already been set up. There was J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI, for a start. In 1938 Congress set up the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC or HCUA), to investigate Americans accused of disloyalty. At first the committee only investigated the Ku Klux Klan and German-Americans who might be Nazis, but when they found no serious threat there, the committee started investigating allegations that communists had infiltrated the New Deal's Works Progress Administration.(32) During the World War II years the committee had little to do, except build a file containing the names of a million known or suspected Communists, "fellow travelers," "premature anti-fascists," "dupes," and "bleeding-heart liberals," to use some of the popular epithets of the time. When the Cold War began, the resulting scare was a godsend to the committee. We'll be hearing a lot soon from one committee member, a young California congressman named Richard Milhous Nixon.(33)

On March 21, 1947, Truman signed Executive Order 9835, also known as the "Loyalty Order," which called for a loyalty investigation of every federal employee. During the next four years, more than three million employees were investigated; of those, 99 percent were cleared. About 5,000 were allowed to resign when suspicions arose while they while being investigated, 378 were dismissed as "security risks," and only one was charged with being a spy. That one was 27-year-old Judith Coplon, who was arrested for taking FBI reports to a Russian friend at the United Nations. Actually what she thought were secret government documents were fakes, planted by J. Edgar Hoover, and though convicted of espionage and conspiracy, those charges were later dropped because of a technicality; the FBI had bugged her telephone while she was talking with her attorney.

1947 also saw the creation of the "Hollywood Blacklist." For nine days HUAC held hearings on alleged communist influence in the entertainment industries.(34) Already Hollywood had a reputation as a liberal place, because some directors, actors, producers, etc. had been members of the Communist Party in the past, and while films made during World War II promoted the wartime alliance with the USSR, they could be seen as procommunist propaganda as well. Of the eleven "unfriendly witnesses" who were called on to testify, the only one that did was the playwright Bertolt Brecht; the others, all screenwriters and directors, refused to answer the committee's questions, and were charged with contempt of Congress. To prove they were loyal in the struggle against communism, Hollywood studios refused to employ the so-called "Hollywood Ten" until they were cleared of contempt charges and had sworn they were not Communists. During the next few years, the blacklist was expanded to include more than 300 individuals, prompting the committee to hold a second series of investigations in 1951. Some of the actors blacklisted, like Charlie Chaplin, left the United States to find work abroad, while screenwriters wrote under pseudonyms or the names of colleagues. It was not until 1957 that anyone involved in motion pictures or television had any success in breaking the blacklist. Because of this, and because of Joe McCarthy's activities (see below), you will hear many, especially liberals, denounce the Cold War era as a modern-day "witch hunt," though as you can see, some Communist sympathizers really existed.

The most notorious un-American activity involved one of the last promising New Dealers, Alger Hiss (1904-96). Hiss had served for ten years in the State Department, traveled with FDR to Yalta, and had been acting secretary-general when the United Nations held its first conference at San Francisco. In 1948, Whittaker Chambers, a senior editor for Time Magazine, went before the House Un-American Activities Committee and accused Hiss of being a Communist. Chambers had once been a Communist himself, and spied for the Russians in the mid-1930s, but quit in 1938, after becoming disillusioned by Stalin's purges; he feared that if hit men working for Stalin could reach far enough abroad, he might become a victim of the purges, too. To convince the Soviets he was too valuable to kill, Chambers stole stacks of documents from the State Department, which he called his "life preserver"; later he claimed that Hiss had gotten the documents for him. One night in December 1948, Chambers went with two HUAC investigators to his Maryland farm, and showed them a hollowed-out pumpkin where he had hidden five rolls of microfilm; hence, the documents were called the "Pumpkin Papers." The contents of the rolls of film were not made public until 1975; one roll was blank because it had been overexposed, while two had non-classified information on US Navy equipment like parachutes, life rafts, and fire extinguishers. The other two rolls, however, had photographs of the State Department documents, which would become proof of a Communist conspiracy in prewar Washington. Chambers also provided some documents that had been copied by typewriter; later it was shown that Hiss owned the brand of typewriter (Woodstock) used for that job.

The hiding place for the Pumpkin Papers.

Two trials followed, in 1949 and 1950. Truman was not pleased to learn that his main man in the UN was a Communist, and dismissed the Hiss case as a "red herring," meaning he thought it was a distraction. Most of the time the question was whether Chambers or Hiss was lying, until the Pumpkin Papers decided the matter. The first trial ended with a hung jury, while the second found Hiss guilty on two counts of perjury; he was sentenced to five years in prison. Though he only served forty-four months of that sentence, Hiss spent the rest of life on a quest to clear his name of the perjury charges. As for HUAC, it stuck around until 1975, when its job was transferred to the US Justice Department.

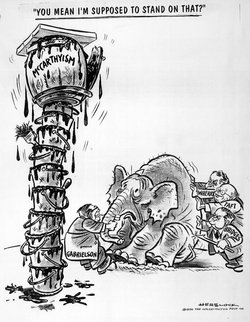

While the Hiss trials were going on, one man appeared to take full advantage of fears about the "Red menace": Wisconsin Senator Joseph R. McCarthy. McCarthy unloaded a bombshell when he spoke at a meeting of 275 Republican women in Wheeling, West Virginia, on February 9, 1950. They had gathered to observe the upcoming birthday of Abraham Lincoln, but instead, he held up a piece of paper and declared that the State Department was full of Communists, saying, "While I cannot take the time to name all the men in the State Department who have been named as members of the Communist Party and members of a spy ring, I have here in my hand a list of 205--a list of names that were known to the secretary of state and who, nevertheless, are still working and shaping policy of the State Department." During the next few days McCarthy muddied his case, asserting that the list had 57 or 81 names on it, instead of 205. Still, it made him a national figure. Other Republicans had accused the Truman administration of being soft on communism, but when it came to making accusations without verification, McCarthy outdid them all.

Because of the recent reverses in Asia, McCarthy's wild charges made sense to many people.(35) When he denounced Owen Lattimore, a leading China expert, as the "top Russian spy" in America, it caused such an uproar that the Senate appointed a special investigating committee under Maryland's Millard Tydings. Those hearings kept McCarthy in the news for the rest of 1950. Encouraged by Republican leaders and his growing notoriety, McCarthy went after other targets in Washington, D.C., even attacking General George C. Marshall, who was now Secretary of Defense.

By the time of the Truman administration, the White House was nearly 150 years old, and suffering from structural problems. These became apparent because Truman liked playing a piano that belonged to his daughter. Here's what he said about his piano playing: "My choice early in life was either to be a piano player in a whorehouse or a politician. To tell the truth, there's hardly a difference." Anyway, one day a leg of the piano fell through the floor, and it was decided to evacuate the First Family, so that repairs and a reinforcing of the whole White House structure could be carried out. They were moved in November 1948 to Blair House, a nearby building that had been used as a place where guests of the president could stay, especially visiting heads of state. There they stayed for most of Truman's second term. When the First Family felt the urge to get away from DC, they could go to a "southern White House" in Key West, Florida. They returned to the original White House in March 1952, ten months before Truman's presidency ended.

Finally, two territorial changes worth mentioning took place during the Truman years, both of them having to do with islands captured in the Spanish-American War. On July 4, 1946, independence came to the Philippines. FDR had promised to turn the archipelago loose in 1945, but World War II came first, so the Philippines wasn't really ready for independence, even after a one-year delay to help rebuild the local infrastructure. Still, Truman felt the United States should honor its agreements to the best of its ability.(36)

The other change involved Puerto Rico. In 1946, Truman began the process of loosening Anglo-American rule by appointing that island's first Puerto Rican governor. After that, Puerto Ricans were allowed to elect their own governors, and they drew up a constitution that would treat Puerto Rico as more than just a conquered territory. That constitution was completed in 1952, and Puerto became a "commonwealth," still part of the USA, but an autonomous territory handling all affairs not involving defense or foreign policy. Not everyone was satisfied by the arrangement, though. Some Puerto Rican nationalists thought US rule up to that point had been too heavy-handed, and for them only complete independence would do. When they saw they weren't going to get what they wanted, the nationalists staged an uprising in 1950, which was quickly crushed. Two of the nationalists came to Washington, D.C. and staged an unsuccessful assassination attempt on Truman, killing a policeman before both of them were gunned down. Since then, Puerto Rico has done better than the rest of the Caribbean, but it remains poorer than any state on the US mainland. Consequently there have always been some Puerto Ricans who don't like their island's halfway status, and from time to time the government allows a plebiscite on the issue of whether they should become independent, or become the 51st US state. A majority of the residents, however, like their situation the way it is, and have voted to keep the commonwealth every time.

"I Like Ike"

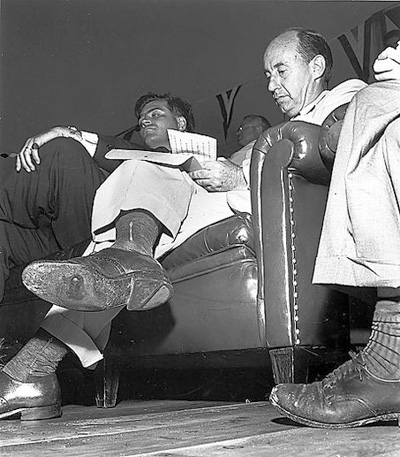

After World War II, General Eisenhower was so popular that he could have gotten the presidential nomination of either the Republicans or the Democrats, but he chose not to run in 1948. Instead he briefly served as president of Columbia University, and wrote a book, Crusade in Europe, before going back to Europe to lead the new NATO army. He changed his mind, however, by the time the campaign for the 1952 presidential election began. The Republican front runner was Senator Robert Taft again, and Eisenhower entered as a Republican because he thought Taft's conservative isolationism was bad for both the nation and the party. With Eisenhower leading the moderate wing of the GOP, the race between him and Taft was too close to call during the primary phase of the campaign. The Republican convention was a bitterly contested one; emotions were running high because Taft, who was sometimes called "Mr. Republican," told his supporters this would be the last time he ran for the White House. In the end the delegates decided to nominate Eisenhower on the first ballot, figuring he was more electable than Taft. Then Eisenhower made a deal with Taft to reunite the party; he would pursue a mostly conservative domestic policy, if Taft would stay out of foreign affairs, and picked a fiercely anticommunist running mate, Senator Richard M. Nixon.

The 22nd Amendment did not apply to whomever was president when it was ratified, so Truman tried running again. But his firing of General MacArthur had made him very unpopular, and most of the voters agreed when Republicans asked, "Had enough? Had enough of Korea, corruption and communism?" Consequently he lost the first primary, and soon after that, Truman announced he would not seek a third term after all.(37) Vice President Barkley also ran, but at the age of 74, he was considered too old. That left eight other candidates, mostly favorite sons, and at the Democratic Convention in Chicago, party leaders picked the one with the fewest liabilities, Governor Adlai Stevenson of Illinois. For his running mate they balanced the ticket by giving Stevenson a Southern conservative running mate, Senator John Sparkman of Alabama.

Stevenson was a likeable intellectual, and for a Democrat, he couldn't have had better credentials; his grandfather was Grover Cleveland's second vice president, and his father was Woodrow Wilson's friend and the Illinois Secretary of State.(38) Still, running a successful campaign against Eisenhower would have been nearly impossible for anyone. Not only was Eisenhower a big war hero, the voters were also attracted to his all-American background and his cheerful personality; he was the kind of person anyone would want to have for a grandfather. The Republican slogan, "I Like Ike," was one of the simplest ever used in a presidential election, but so successful that afterwards, people liked to call Eisenhower "Ike," rather than use his full name. On the issues, the main one was the Korean War, which now looked like a trap for American soldiers, and Eisenhower settled that with a MacArthur-style promise: "That requires a personal visit. I shall go to Korea."

There was a dramatic moment in September when Nixon was accused of taking too many gifts, and Eisenhower considered dumping him. Before that could happen, though, Nixon went on television to defend his record, stating that the only gift he and his wife had kept was a dog named Checkers. Because it saved his career, the "Checkers Speech" was the first important use of TV in American elections. The final vote was a landslide victory for Eisenhower, where he took 55 percent of the popular vote and 39 of the 48 states. Even four Southern states (Texas, Virginia, Tennessee and Florida) went Republican, showing that the age when the Democrats had total control over the South was almost over.

Eisenhower was a caretaker president, not an activist; indeed, compared with the chief executives before and after him, it seemed that he did not do much at all (the public mainly remembered him playing golf on the White House lawn). The truth was that as a general he had learned to delegate authority, so like the greatest rulers of the past (e.g., Caesar Augustus, Elizabeth I) he could lead without giving the impression of leading. The economy returned to the "normalcy" that marked the 1920s, with low inflation, low unemployment, a rising standard of living, and balanced budgets. Consequently the children growing up at this time, the first of the post-Depression "Baby Boom," came to see prosperity as the normal order of things, and that they had a right to prosper, as if it was a right spelled out in the Constitution.

Big business was especially pleased with the new arrangement, because for the first time since the Coolidge years, Washington had a government that saw things the way they did. In fact, many of the new leaders were corporate executives, like Charles E. Wilson, the president of General Motors. When he became Secretary of Defense, Wilson sold his GM stock to avoid a conflict of interests, after lamenting, "I thought what was good for the country was good for General Motors, and vice versa." Still, GM didn't do badly, thanks to a timely tax cut and military contracts, which were worth $7 billion by 1956. In May 1953 the federal government handed over its offshore oil and gas deposits, worth an estimated $80 billion, to the nearest states (California, Florida, Louisiana and Texas). Like Teapot Dome in the 1920s, offshore petroleum had previously been reserved for future use by the armed forces; Truman had assigned it to the Navy, and vetoed two bills to give it away. Eventually, however, the cooperation between big business and the Department of Defense was too much even for Ike; in his last speech as president (January 17, 1961), he warned of the danger of too much influence by the "military-industrial complex," giving liberals a buzzword they have used ever since.

In foreign policy, there was a slight defusing of Cold War tensions, compared with what they had been during the Truman years. The main reasons for this were an end to the fighting in Korea, and a change of leadership in the USSR. True to his word, Eisenhower visited Korea in 1953 to see the situation for himself, and in July a cease-fire was signed that left North and South Korea in pretty much the same positions they had started from. No formal peace treaty has ever been negotiated to end the war, though, because no formal war declaration was issued when it started. The cease-fire has held to this day, despite crises like the Pueblo incident, when the North Koreans captured an American spy ship (1968), and recent efforts North Korea to build nuclear weapons. Korea's story since 1953 reads like that of postwar Germany: the non-Communist part of Korea has prospered, while the communist part has stagnated. From the American point of view, it may have also helped that after Korea stopped making headlines, the remaining hot spots in the Cold War were in places Americans knew little or nothing about, like Vietnam. Vietnam itself was a problem, because the United States had bankrolled the French military effort there, only to see the Viet Minh besiege and capture Dienbienphu, a defeat so humiliating that the French gave up and got out (1954). The resulting cease-fire left half of Vietnam under Communist control, and when the Communists began infiltrating the other half, Eisenhower was faced with the prospect of another land war in Asia. The fact that he chose not to get involved in Vietnam has made him look wiser than his successors.

Meanwhile in the Soviet Union, Joseph Stalin died, and after a power struggle in the Kremlin, Nikita Khrushchev took his place. Unlike Stalin and Mao Zedong, Khrushchev wasn't anxious to start World War III; he wouldn't sacrifice millions of his own people to achieve the goal of world domination. He was also more willing to put Soviet foreign adventuring on the back burner, to improve the lives of Soviet citizens at home (e.g., the Virgin Lands project in Kazakhstan and southern Siberia). Later on, in the early 1960s, the USSR and China stopped cooperating, mainly because Khrushchev had become Stalin's harshest critic, while Mao still saw Stalin as his mentor. This meant that in a future East-West war, the Soviets and the Chinese would not be fighting on the same side, another factor that would cause every nation to think twice before making trouble. On the other hand, the first hydrogen bomb was exploded in a 1952 nuclear test. Using the heat produced by an atomic bomb to cause a fusion reaction, the new bomb was estimated to be 500 times more powerful than the Hiroshima bomb; the first test vaporized a small coral island, ripped a hole 175 feet deep in the ocean floor, and sent radioactive dust ("fallout") into the stratosphere. Nor was that all; the Russians learned how to build "H-bombs" even faster than they learned to build "A-bombs; by 1955 the USSR also had a thermonuclear weapon that worked. This meant that if either the US or USSR used nuclear weapons in a future conflict, the most likely result would be the obliteration of both sides in a matter of hours, now that they had arsenals with enough nuclear power to kill everyone in both nations several times. For the rest of the Cold War years, the strategy of the superpowers would be to build more warheads than the other side had, and use the threat of "mutual assured destruction" (MAD) to keep anyone from actually using them.

The nuclear rivalry between the superpowers was not only more dangerous because the bombs gave a bigger blast; there were also more ways to deliver them. Whereas the first A-bombs had to be dropped on their target from an airplane, the 1950s saw the development of missiles big enough to carry a nuclear warhead. These were more dangerous than bombers, because missiles were much harder to shoot down, and when stored in hardened silos, they were difficult to take out even before a launch. Then in the 1960s, submarines capable of launching missiles were built; these were less accurate than land-based missiles, but harder for the enemy to locate. The US armed forces started talking about defending the United States with a "triad" composed of bombers, ICBMs, and submarines. But the additions to nuclear arsenals didn't stop there. MIRVs, missiles with more than one warhead, each capable of hitting a different target, were developed in the 1970s, and low-flying, very accurate cruise missiles were added in the 1980s. Consequently it was now impossible for any nuclear attack by either superpower to be so thorough, that the victim would be left without the ability to respond with a massive retaliation.

During the first two years of the Eisenhower administration, his main opponent was not a foreign power or a Democrat, but Joe McCarthy. With the Republicans back in control of the Senate, McCarthy became chair of the Subcommittee on Investigations of the Senate Committee on Governmental Operations. From this position, be continued to look for Reds, though he never provided a single, courtproof example. Apparently he forgot who won the recent election, because the individuals he attacked were now members of his own party.

First, McCarthy embarrassed the Secretary of the Army, by launching a highly publicized investigation of the Voice of America and the Army Signal Corps. Other objects of McCarthy's wrath included former Minnesota Governor Harold Stassen, head of the short-lived Foreign Operations Administration and the president's "Secretary of Peace" (he earned that nickname by presiding over sessions on disarmament); media publications like The Saturday Evening Post; and even Eisenhower's Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles. By early 1954, a Gallup poll rated McCarthy as the fourth most admired man in America. He stepped too far, however, when he took on the army again, this time because a general gave an honorable discharge to an army dentist with communist ties. Though the general in question had fought at the Battle of the Bulge, McCarthy called him "not fit to wear that uniform." Because McCarthy hounded the general in committee meetings and on the Senate floor, a special congressional committee was set up, to investigate the attempt by McCarthy and his chief counsel, Roy Cohn, to make the army grant special treatment to another McCarthy aide. These hearings were televised, and they showed McCarthy as a blustering bully. In December 1954 the Senate voted to censure him for conduct that "tended to bring the Senate into dishonor or disrepute"; he was only the fourth senator in US history to receive such a punishment. After that, folks no longer took him seriously, and they called him names like "political hoodlum" and "dangerous buffoon." Three years later he was dead from hepatitis, brought on by the heavy drinking that may have caused his bizarre behavior.(39)

To head the Supreme Court, Eisenhower picked Earl Warren for the job of chief justice. When we last saw Warren, he was the Republican governor of California, and he had also been the GOP's vice presidential candidate in 1948, so to Eisenhower he must have looked like a safe choice. Imagine the surprise when instead, he became the most liberal chief justice in recent history; the Warren Court (1953-69) took a more activist role in government than any other Supreme Court had done.

The first issue in which the Warren Court intervened was civil rights, continuing the moves toward racial equality that had already started in the military, sports and entertainment fields. At this point the controversy was over public schools in the South. In all of the fifteen former slave states, plus West Virginia and Oklahoma, white and black students had been going to different schools for decades, and an 1896 Supreme Court decision declared those schools "separate but equal," but any visitor to the Negro schools would have known they weren't equal at all. In the Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka decision (1954), the Supreme Court unanimously voted to desegregate Southern schools, calling the previous arrangement a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. Enforcing the decision, though, would be a tougher matter, and the Court knew it. It waited a year before ordering the Southern states to desegregate, and gave the lower federal courts the powers needed for enforcement. By the end of Eisenhower's first term, they had successfully integrated 320,000 black students into the white schools of nine states and the District of Columbia. However, those were the old "Upper South" and border states. The other eight states were hard-core members of the former Confederacy; their 2.5 million black children would be harder to integrate, and they faced stronger resistance. In Little Rock, AR, a federal court ordered a high school to enroll nine black students, and the president invoked the Insurrection Act, using the Arkansas National Guard and the 101st Airborne Division to make sure that order was carried out, because Governor Orval Faubus opposed it (September 1957).(40)

After that the process of opening schools to members of any race went easier, but a 1971 decision, calling for the busing of students to schools outside their home communities to create more integrated school populations ("forced busing") was controversial--and unpopular--all through the 1970s and 1980s. In fact, one of the longest--and most violent--protests against busing and desegregation happened not in the South but in a Yankee stronghold, Boston. Children ended up spending nearly two hours a day on school busses, to meet the goals of desegregation. Fortunately, forced busing is no longer needed, because the modern American community is racially integrated to the point that any residential neighborhood is likely to have white, black, Hispanic and Asian students.

Whereas school desegregation was imposed on the nation by the government, other civil rights activity was generated by the people. The best example of this was the Montgomery Bus Boycott. In Montgomery, Alabama, blacks were required to sit in the back of public busses, and had to give up their seats if there weren't enough for all the white passengers. In March of 1955, a fifteen-year-old girl, Claudette Colvin, was arrested for not giving up her seat to a white person. The black community of Montgomery did not respond then, but the next time it happened, the woman in question was a seamstress named Rosa Parks (1913-2005). Parks also happened to be secretary to the local chapter of the NAACP, so she was too important to ignore. The black leaders of Montgomery organized a boycott of the city's bus system, which would be led by a twenty-six-year-old pastor, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. The city government earned a large portion of its income from public transportation, so the effect of the boycott was immediate, and devastating. Instead of riding buses, participants in the boycott organized car pools, hitchhiked, rode in taxis, and resorted to older methods of transportation such as cycling, walking, or even riding mules or driving horse-drawn buggies. Soon Montgomery got the rest of the country's attention, and on June 4, 1956, the federal district court ruled that Alabama's racial segregation laws for buses were unconstitutional. However, an appeal allowed the segregation laws to remain on the books, so the Supreme Court had to step in and uphold the district court's ruling. Thus, the boycott continued until the leaders of it knew they had won; they finally ended it on December 20, 1956, 381 days after it started and one month after the Supreme Court's decision. Now black passengers could sit anywhere on the busses, but even more important, this victory had been achieved through civil disobedience, not violence. Moreover, it made Martin Luther King the leader of the civil rights movement.

Life in the 1950s

To an adult living in the 1950s, the threat of nuclear annihilation was always present. Americans coped with it by building bomb shelters if they could afford them, and schools staged air raid drills--just in case, of course. Aside from that, though, they would have felt life was getting better, thanks to the current prosperity and advances in electronic and medical technology (e.g., Dr. Jonas Salk introduced his polio vaccine at this time). Overall, it was a decade that emphasized conformity, perhaps best characterized by TV shows like "Leave It to Beaver" and "Father Knows Best." There were new writers and artists, like Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, James Michener, Tennessee Williams, Andrew Wyeth and Jackson Pollack, but overall American culture at this time must have seemed less lively than it had been previously.

There were also new cultural movements outside of the American mainstream, for anyone who cared to look. One was the beatniks, forerunners of the hippies who called themselves "the beat generation" (hence the name), and gathered in coffeehouses to recite poetry; they considered themselves intellectuals because nobody else understood what they wrote! Another was the rock and roll revolution in music. In Chapter 4 we noted the rise in popularity of ragtime and jazz, and noted that black musicians led the way in popularizing those genres. But cultural innovation did not stop there; in the 1930s and 40s, the blues and big band music joined the American scene. Then in the early 1950s, jazz was transformed into rock and roll.(41) As with ragtime and jazz, the earliest rock musicians were black: Ike Turner, Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, Little Richard, Bo Diddley, etc. What was different was that this time, a number of white artists, like Bill Haley and Jerry Lee Lewis, quickly caught on. The most successful of the latter was Elvis Presley, who combined white and black music styles with uninhibited performances (for a while he could only be shown on TV from the waist up). When he became popular, rock and roll took over the mainstream culture, dictating not only sounds but also items like art (e.g., the psychedelic posters of Peter Max), fashion and language. Nor was it limited to the United States; the 1964 "British invasion" by the Beatles is seen by many as one of the key events of modern times.

The greatest achievement of the Eisenhower administration was the creation of the Interstate highway system. In Chapter 3, footnote #32, we saw the construction of the National Road, but it stopped before it even reached the Mississippi River, and road-building had been neglected since that time, as the nation built first canals, then railroads. The roads that existed outside the cities were mainly "market roads," whose condition depended on whether county and state governments were willing to spend money to maintain them.

The invention of the automobile generated a demand for a better road system on a national scale, and construction on the Lincoln Highway, the first road going all the way across the continental United States, began in 1913. When completed, the Lincoln Highway ran from New York City to San Francisco, but traveling along its entire course was still a "sporting proposition." To make such a trip in thirty days, the driver had to go at an average speed of 18 miles an hour for six hours per day (driving was only done during daylight hours). Because gas stations were uncommon in many areas, the smart driver stopped to fill up at each one, whether he needed it or not. If water covered part of the road, the driver was encouraged to wade into the water before driving through it, to make sure it wasn't deep enough to stall the engine. A motorist preparing to drive from coast to coast had to pack supplies and tools like one of history's great explorers. One travel guide recommended chains, a shovel, an axe, jacks, tire casings, inner tubes, tools, and a pair of Lincoln Highway pennants; it also said, "Don't wear new shoes." West of Omaha, the driver no longer had to arm himself against Indians, but full camping equipment was recommended; he was also told to avoid drinking brackish water and to get advice/help from anyone he passed along the way.

The Federal Aid Road Act of 1916 authorized federal funding for road-building, but still the highways had to take a back seat to events like two world wars, the Great Depression, and the Korean War. Franklin Roosevelt, for example, expressed great interest in an interstate road system, but all he did was take a map of the United States, draw three north-south lines and three east-west lines on it, and ask the Bureau of Public Roads to build it. Some useful highways were built in the forty years after the Federal Aid Road Act--two of the most famous were US Route 1, which followed the east coast from Key West, FL to Fort Kent, ME, and US Route 66, which ran from Los Angeles to Chicago. However, they handled traffic the same way as previous roads, so they didn't offer much of a challenge to the railroads, which could still deliver larger cargoes in less time.

Eisenhower had a personal interest in highways because of his own experience. As a young soldier, he was in the U.S. Army Transcontinental Motor Convoy of 1919, which took two months to go from Washington to San Francisco, mostly by following the Lincoln Highway. Because of problems the convoy suffered (e.g., broken bridges, stuck vehicles, etc.), he marveled that traveling through a modern nation should be such a wild adventure, and later wrote a chapter about it called Through Darkest America With Truck and Tank (from At Ease: Stories I Tell to Friends). Then in the 1940s, he saw how efficient Germany's Autobahn system was, when it came to moving people and things quickly. On June 29, 1956, he was in the hospital recuperating from surgery (see below), but that didn't stop him from signing the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, which authorized the creation of the "National System of Interstate and Defense Highways." What made this act different from the 1916 act was that the federal government promised to pay 90 percent of construction costs, using revenues from tolls and gasoline taxes.

Modeled after the Autobahns and the Pennsylvania Turnpike, the Interstate system allowed only fully motorized vehicles to use it, and restricted access to other roads, so that traffic could travel full-speed, without the need for traffic lights or stop signs. Standards for the highways included 12-foot-wide lanes, 10-foot-wide paved right shoulders, 4-foot-wide paved left shoulders, and curves to allow driving at speeds of 50-70 miles per hour. And because it was decided that the Interstates should service every city with a population of 100,000 or more, every state except Alaska eventually got them (even Hawaii did, but since that state is a cluster of islands, the Hawaiian Interstates only go around Oahu).

The decision to have Interstates go to every major city was the most important one, for it meant that this time the South wouldn't be short-changed; its cities would finally get the infrastructure they deserved. Indeed, the lack of roads was one reason why most Southerners, both white and black, had stayed in the South, even though they could earn much more money working in the North. Now with the newest roads connecting the South with other regions, the South no longer had to be the most backward part of the country, socially as well as economically. The rest of the twentieth century saw a migration of people and businesses into the South, to escape high taxes and cold winters; as this happened, the South caught up with the North and the West, finally regaining the importance that it had before the Civil War years. We will discuss how the North-South migration affected the nation in the last part of this chapter.(42)

For better or for worse, the Interstates also contributed to a homogenization of American society. In Chapter 4, footnote #41, we saw that the telegraph and the railroad were the two most important tools used to civilize the West. Likewise, because the Interstates improved transportation and communication, there would be fewer differences between the states than had existed previously. Nowadays it is just a joke when a resident of Massachusetts claims he cannot understand the language of Alabama, or vice-versa.

The transformation of America by the Interstates wasn't noticed until after Ike was gone, because the highways took decades to build. By 2004, the entire system had 46,837 miles of roads. The project was declared complete with the finishing of Interstate 70 through Colorado in 1992. However, construction on one stretch of road from the original plans, the part of I-95 just northeast of Philadelphia (the "Pennsylvania Turnpike/Interstate 95 Interchange Project"), only started in 2010, and it was finally completed in 2018. Because of the Interstate network, today a motorist can drive to almost any part of the continental US in a few days (and also much of Canada, thanks to the Trans-Canada Highway); all he needs is gas money and a strong tolerance for fast food, caffeine, and public restrooms.

And that's not all; new Interstate projects that weren't on the original plans have been built over the years, mostly beltways and other auxiliary routes. The highways that have not been finished include Interstate 22, which will connect Memphis, TN with Birmingham, AL; Interstate 66 (not to be confused with the famous Route 66), which was supposed to run east-west across the continent, but only the part connecting Washington, DC with northern Virginia was completed; and a spectacular extension to Interstate 69. Currently I-69 goes from Port Huron, MI to Indianapolis, IN; if the extension is ever finished, it will run south-southwest all the way to Laredo, TX, becoming a "NAFTA Superhighway" connecting the industrial centers of Canada, the US, and Mexico.

For those who remembered 1952, the 1956 presidential election must have looked like a rerun. The Republicans nominated Eisenhower again, as you might expect, and the Democrats gave Stevenson another chance. For the vice presidential choices, Eisenhower kept Nixon, though he was still a controversial character, while Stevenson let the Democratic convention choose a rival, Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee, to run with him. Another candidate, Senator John Fitzgerald Kennedy of Massachusetts (Joseph Kennedy's son), was narrowly beaten by Kefauver, so from that time on, Kennedy was running to be the presidential nominee in 1960.

The Korean War was over, and the economy was doing well, so the only issue that generated much interest was the question of Ike's fitness for another term. He had suffered a heart attack in the fall of 1955, and he had an operation in 1956 to reopen a blocked intestine (ileitis). Consequently, his recovery ensured another victory. Then in October came the most dangerous foreign situation during the Eisenhower years: the second Arab-Israeli war and the Soviet Union's crushing of a Hungarian uprising both occurred during the same week. Fortunately, those crises passed without triggering World War III, and Eisenhower won by an even greater margin than he had in 1952; this time 57 percent of the popular vote and all but seven states were his.

Most presidents have a tougher time in their second term than in their first (see my essay on term limitations for a list of second-term challenges). Eisenhower kept tax rates high, for the purpose of paying down the national debt from World War II, and that had the side effect of causing two recessions, one in 1957-58 and another in 1960. His other challenges, however, had nothing to do with spending. One was how the Soviets sprung more than one surprise. In August 1957 they announced their first successful test of an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM). Then on October 4, 1957, the USSR launched the first satellite into orbit, Sputnik I. Americans had thought they would begin the space age, so the knowledge that the Russians had larger and better rockets came as an awful shock. By contrast, the main American achievement for that year was Ford's creation of the Edsel, possibly the most notorious failure in the history of auto manufacturing and marketing. Though the Americans had captured Werner von Braun, Nazi Germany's foremost rocket scientist, at the end of World War II, American rockets in the 1950s showed a disturbing tendency to blow up on the launch pad, like the one that failed to launch the first American satellite in December 1957. Many Americans started talking about the danger of allowing a "missile gap" between them and the Soviets.

We saw how World War II battles had been decided by who controlled the air; now it was felt that the nation that controlled space would control the future. Thus, the new Soviet threat to American technology and security made it imperative to catch up with the Russians. Many felt the reason why the Americans were lagging was because educators didn't teach math and science as well as they used to, so crash programs were launched to improve those curricula. Another result was the creation in 1958 of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), to handle space exploration.(43) The first months of 1958 also saw the successful launch of two American satellites, Explorer I and Vanguard I. Nevertheless, the Russians maintained their lead in the "space race" well into the 1960s. By the end of the 1950s, they had launched a satellite carrying a live passenger (a dog named Laika), and successfully sent two space probes to the moon, of which one made a hard landing, while the other took the first photograph of the moon's far side.

The other unpleasant surprise was Cuba. Ever since the United States had granted Cuban independence, in the aftermath of the Spanish-American War, Cuba had been in the American orbit; American businessmen and tourists were a common sight in Havana. For most of the period from 1933 to 1958, Cuba was ruled by a typical Latin American dictator, Fulgencio Batista. Although Batista was pro-American, Washington eventually got tired of him, so when he was ousted by a revolutionary named Fidel Castro (January 1, 1959), Americans felt relieved. Unfortunately, Castro soon proved to be no improvement. Americans changed their mind about him when he executed hundreds of Batista associates, and began to seize US property in Cuba. Even worse, he launched an anti-American propaganda campaign, and started acting friendly with the Soviet Union and China. The United States responded by expelling Cuba from the Organization of American States, and broke diplomatic relations with Cuba in January 1961. We don't know if Castro was a Communist when he seized power (he didn't call himself a Communist until December 1961), but his improving ties with Communist governments, and the American reaction, made sure his transformation would be complete. The result was a Communist nation only ninety miles south of Florida, and the beginning of an ongoing exodus of Cuban refugees, fleeing from Havana to Miami.

The good news is that two new states were created in Eisenhower's second term. Since 1912, there had been forty-eight US states. Because the American flag is changed every time a new state joins the Union, the forty-eight-star flag was in use for forty-seven years, longer than any previous flag. Then in 1959, Alaska and Hawaii became the forty-ninth and fiftieth states respectively. With that, the United States reached its present-day boundaries (not counting the Panama Canal and the islands mentioned in footnote #36) and took on its present-day appearance. Because fifty years have passed since then, the flag with thirteen stripes and fifty stars has become the only flag to outlast the forty-eight-star one.

This is the end of Part II. Click here to go to Part III.

FOOTNOTES

18. Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt had not been faithful to each other for a long time. As early as 1916, Franklin started an affair with Eleanor's secretary, Lucy Page Mercer. Two years later, Eleanor discovered the love letters between Franklin and Mercer, and offered a divorce. A divorce would have ruined FDR's political career, and his mother threatened to disinherit him if they broke up, so he promised not to see Mercer anymore. That saved the marriage, but from then on it was only a marriage of convenience.

FDR managed to see Lucy Mercer a few more times, until she got married in 1920. Then he started a new affair with a campaign worker, Marguerite "Missy" LeHand. Eleanor knew about it, but instead of complaining, she found a soul mate of her own in Lorena Hickok, a cigar-smoking lesbian journalist. This caused a complicated situation in the White House, as accommodations were made for LeHand and Hickok, but it was also required that Franklin didn't see Hickok, and that Eleanor didn't encounter LeHand. Eventually Hickok fell in love with a tax-court judge, and LeHand died in 1941, so Eleanor and Franklin each had at least one more affair after that. Finally, after Lucy Mercer's husband died, Franklin resumed his relationship with her, and she went with him to Warm Springs. The result was a sticky situation in that Mercer was there when FDR died, but Eleanor wasn't, so Mercer had to be rushed out while the first lady was being rushed in.

At least four other presidents besides FDR were philanderers: Harding, Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson and Clinton. Among all of them, only Clinton's affairs were widely known while he was in office.

19. A few days after Truman succeeded Roosevelt, the Soviet foreign minister, Vyacheslav Molotov, came to the White House to introduce himself to the new president. After the formal greetings, Truman called Molotov back for a second interview and told him what he really thought about what was happening in Poland. Furious, Molotov exclaimed, "I have never been talked to like that in my life!" Truman's reply was to the point: "Carry out your agreements, and you won't get talked to like that."

20. "Is there anything we can do for you? For you're the one in trouble now."--Eleanor Roosevelt's response to Truman, after he asked if there was anything he could do for her.

21. Truman always took responsibility for his actions, and he let everyone know it with a sign on his desk that said, "The buck stops here!" He also was a blunt, earthy talker, unafraid to speak his mind ("If you can't stand the heat, you better get out of the kitchen."). For example, while campaigning for Adlai Stevenson in 1952, he described his ally as "a man who could never make up his mind whether he had to go to the bathroom or not." Republicans got even worse treatment; he called Richard Nixon "a shifty-eyed g*dd*mn liar," and General MacArthur "a man there wasn't anything real about." His words, not toned down by any diplomacy, made every other politician look like a crook, by comparison.

The best-known story about Truman's language concerns a speech he made at a Washington horticulture show. He started by saying, "I've been a farmer all my life, and I know that farming means manure, manure, manure and more manure." He went on to say that good manure must have been used to grow the flowers at the show, and one offended lady in the audience asked Margaret "Bess" Truman, "Bess, couldn't you get the president to say 'fertilizer'?" The first lady responded, "Heavens, no. It took me twenty-five years to get him to say 'manure.'"

22. Eleanor Roosevelt served as one of the first delegates from the United States at the UN, from 1945 to 1951. For that, and involvement in various humanitarian causes for the rest of her life, Truman gave her the title of "First Lady of the World."

23. For more about the Cold War from a non-American perspective, go to Chapter 4 of my Russian history and Chapter 17 of my European history.